Where K Street NE passes underneath tracks that guide trains into D.C.’s Union Station, lies a tent community that some of the nation’s capital’s homeless call home.

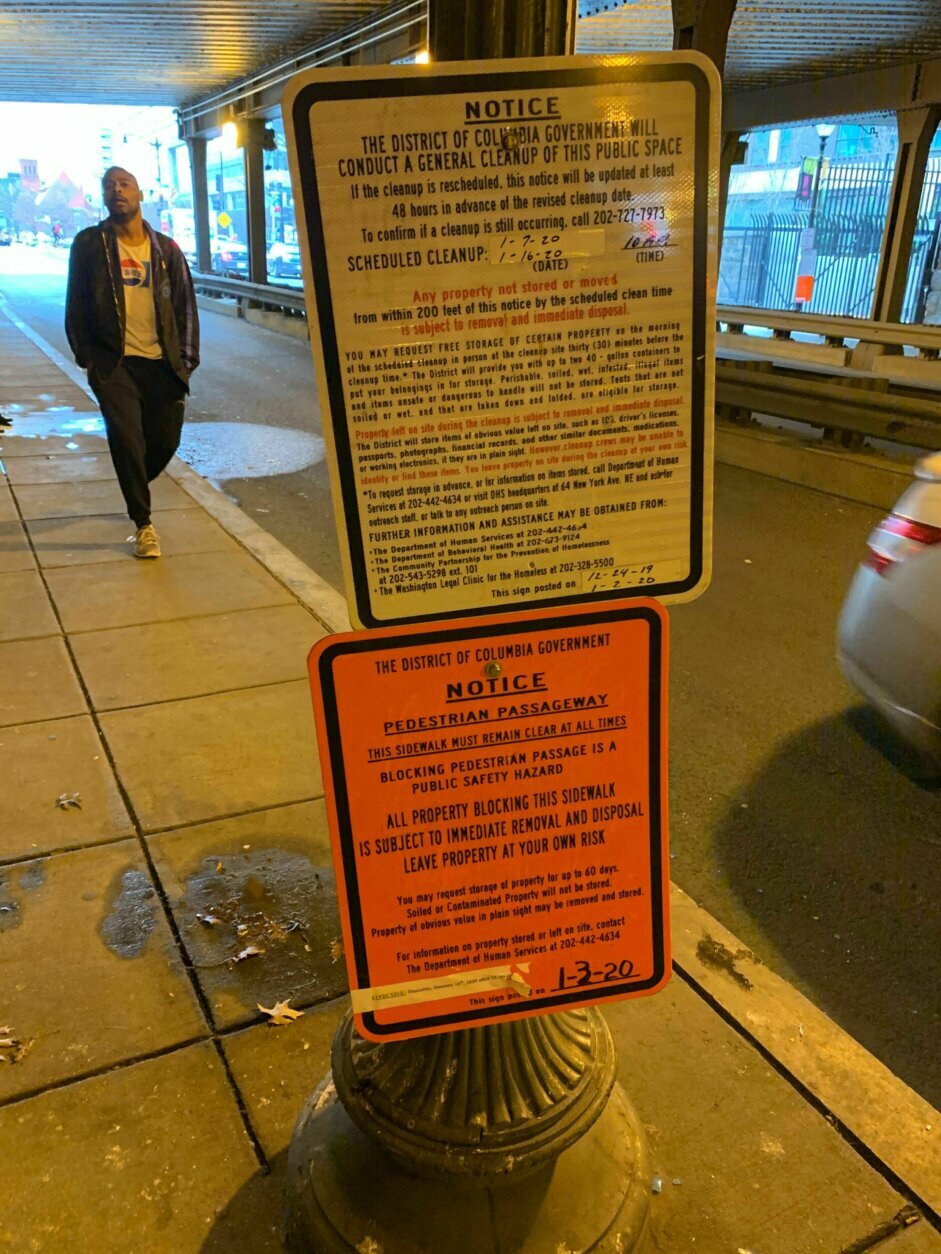

The tents line the sidewalks on both sides of the road. But now next to the tents is a sign that effectively tells the people who live in the underpass that they must pack up and move out by Thursday.

D.C.’s “Encampment Protocol Engagement” happens on that day, during which the sidewalks will be cleared and cleaned.

But what’s different about the process this time is that once complete, tents and belongings cannot return to the walkways.

“We began to notice that people were stepping into traffic to negotiate the overpass,” said Wayne Turnage, Deputy Mayor for the District of Columbia Health and Human Services.

Turnage and his team decided that the sidewalks at the underpass needed to become a pedestrian safety zone.

For some who live in the underpass, the news was upsetting.

One man, who identified himself as Jim, said he believes this comes as a result of complaints about some of the people who live in the community from people who walk through the area. He said the city should work with the people who live in the underpass instead of kicking them out.

“They’ve [the city has] got an obligation to pay attention to us, and they’re not. Instead of helping us, they are punishing us,” Jim said.

Advocates for the homeless are also speaking out about the news.

Ann Marie Staudenmaier, a staff attorney for the Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless, said she believes the people who live and work in nearby buildings may be behind the city’s decision to clear the street.

“Folks who live in those luxury housing units are the ones complaining to the mayor’s office, and I believe that is why they decided to pick now to kick everybody out of that underpass,” Staudenmaier said.

One public complaint about encampments throughout the neighborhood, known as NoMA, came from Robin-Eve Jasper, president of the NoMa Business Improvement District, which published an open letter online about what they called worsening conditions at the sites.

“Bloody hypodermic needles and other drug paraphernalia, rotting food, trash, broken glass, public nudity, prostitution, sales of illegal drugs, and human urine and feces are encountered by those whose routes take them by the encampments,” Jasper wrote.

Turnage argued the move to clear K Street NE by the city is not driven by complaints about the community being there.

“If that were the case, we would be going after encampments in other parts of NoMa,” Turnage said.

Staudenmaier said that the organization is looking into possible legal avenues that could be taken to benefit those being forced out. In the meantime, she spent Monday night speaking with the people who live in the tents about their legal rights.

She feels the city could have done more to help the people who live there find other place to stay and also have waited until after winter to remove them.

“I don’t believe that the city has followed through with its promises to really engage people and find them a safe alternative as of this Thursday,” Staudenmaier said.

She said that some sort of compromise could be made, which would allow those who live there to stay.

“Kicking people out of this particular underpass means that there are about 40 folks who have nowhere else safe and dry to go with their tents,” Staudenmaier said.

Turnage said his teams have worked with those in the tent community and have helped them find alternate places to live.

And on the day of the “Encampment Protocol Engagement” on Thursday, they plan to do the same by informing the people who live in the underpass about their options, assessing their needs and determining where they fall on the waiting list for permanent supportive housing.

Not everyone who lives in the community disagrees with the city’s position. Mike Harris has six tents in the underpass, which he and others live in. He said that in the past eight months he has lived there, the tent numbers have increased dramatically.

“I’ve also seen the litter increase. I’ve seen the noise from arguments, fusses and fights, and stuff increase. It’s time for change,” Harris said.

He pointed across the street at a tent, which is positioned not far from the roadway on the sidewalk.

“I can’t go down that sidewalk over there, because someone decided to put his tent up in a position where I can’t get by. I’m in a wheelchair,” Harris said.

Harris said before the additional tents showed up, the sidewalks were clear enough for pedestrians to get by.

“The city has to do, what they have to do, and unfortunately in this case, we’ve got to move,” Harris said.

Harris said he has been accepted for permanent housing and will move into the apartment in the coming weeks. Until then, he plans to set up his tent nearby.

As for Jim, he said he hopes there is another place for him to move his tent close by.

“Honestly, if I can’t go to the next street over, all right, I’ve got nowhere to go,” Jim said.