This article was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

An appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court by Second Amendment activists in Maryland could affect protections for police officers and the public’s right to document the activities of law enforcement.

The case, which began as the arrest of two protesters outside the State House in February 2018, could have implications on both qualified immunity for police officers as well as the right to video record police in the performance of their duties while in public.

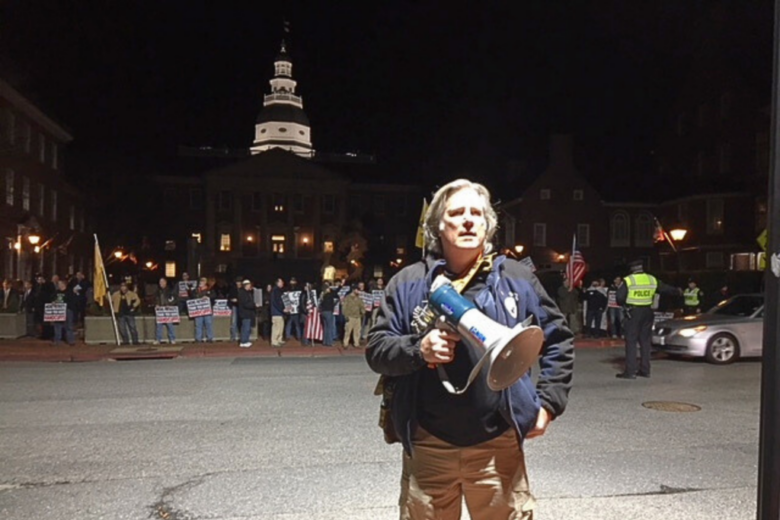

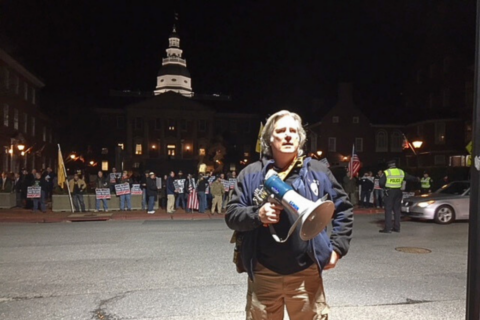

“I think what the Capitol Police are getting away with is a little short of outrageous,” said Mark Pennak, president of Maryland Shall Issue, a Second Amendment rights group that is also a party in the case. “So qualified immunity has to be reconsidered by the Supreme Court and I say that as a lawyer who defended qualified immunity for three decades while at the Department of Justice, but it seems it has been abused too much and has excused too much bad behavior to allow it to go on unaltered. This is our attempt to ask the court to revisit this.”

Pennak’s organization, protester Kevin Hulbert and the estate of his brother Jeff Hulbert, who also was a protester, are asking the U.S. Supreme Court to abolish or sharply restrict the use of qualified immunity for police officers.

They also are asking the court to weigh in on the right to video record police activities in public. Pennak said the 4th Circuit, which includes Maryland, has not ruled definitively on the issue.

“Until or unless the court weighs in on the assertions of qualified immunity, it will continue to be the rule,” he said. “They will always claim that there is no clearly established precedent in the Fourth Circuit that there’s a right to record.”

Six, or about half of, federal circuit courts of appeals have upheld the right to record the public activities of police officers.

“The Supreme Court has squarely ruled that the First Amendment protects the right to gather information, especially about matters of public concern,” said Adam Schwartz, a senior staff technologist at the Electronic Frontier Foundation. “Applying this law, many federal appellate courts have squarely ruled that the First Amendment protects the right to record on-duty police officers. So, police should not have qualified immunity when they interfere with a person who is lawfully recording them. Such recordings serve a valuable public purpose: ensuring police accountability. If Danielle Frazier had not made her recording of the police murder of George Floyd, we might have never heard his name.”

The petitioners are represented by Cary Hansel, a Baltimore attorney. Hansel was not immediately available for comment. The trio filed a request to have their case reviewed by the nation’s highest court on Friday.

The Office of the Attorney General has 30 days to respond, with the possibility of a 30-day extension. The office could also waive filing a response.

A spokesperson for Attorney General Anthony Brown (D) declined to comment on the pending litigation.

Pennak said he hopes to know if the court will hear arguments on the case before the end of the year.

José Anderson, the Dean Joseph Curtis professor of law at the University of Baltimore School of Law, noted there is no guarantee the court will take the case. He said that about 8,000 applications to the court are made every year and about 100 or so cases are accepted.

“The trend towards public recordings being available, despite police disagreement as to how they were taken, is moving towards more freedom to make those visuals available,” Anderson said. “The trend is clearly towards more availability of such recordings. I also would say that it is surprising that courts have not dealt more specifically with the topic in more jurisdictions. This seems like as good an opportunity as any for the Supreme Court to make a definitive statement about something that’s been going on for quite some time.”

The filing is the latest in a case that began more than five years ago.

Jeff and Kevin Hulbert — two brothers, then-members of Patriot Picket, a Second Amendment advocacy group — were part of a small, peaceful protest on a public sidewalk that borders Lawyers’ Mall along College Avenue.

The group is known for frequenting the area on Monday nights during the 90-day legislative session. The signs they carry are sharply worded but the group is peaceful and doesn’t obstruct vehicle or pedestrian traffic.

Initially, Sgt. Brian Pope of the Maryland Capitol Police went to the demonstration after being told by a dispatcher that “someone in the governor’s mansion” called about the group. Pope was asked to “straighten out” the situation, according to the brief filed with the Supreme Court.

Pope was later told that the lieutenant governor “did not want [the protesters] giving him a bunch of stuff for whatever reason,” according to the brief.

Jeff Hulbert, who died in in 2021 after a battle with cancer, was arrested for failing to obey an order to leave the public sidewalk. Kevin was arrested while video-recording his twin brother’s arrest.

Both men were charged that night with failure to obey the lawful order of a police officer.

The pair were issued additional citations the next day after meeting with reporters.

All the charges were dropped four days later. The next week the Hulberts filed a suit in which they alleged that Pope and Col. Michael Wilson of the Maryland Capitol Police violated their First and Fourth Amendment rights. The pair also alleged that they were falsely imprisoned.

A U.S. District Court judge dismissed the suit against Wilson but allowed it to proceed against Pope.

The state appealed the ruling to the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals in Richmond. A three-judge panel overturned the lower court ruling and ordered the case to be dismissed against Pope, saying that the officer was immune because he was acting in the performance of his official duties. A request for a hearing before the full appellate court was denied.

“I think people understand that their rights are at stake,” said Pennak. “The right to petition their lawmakers for redress of grievances, that’s right in the text of the First Amendment. If they can arrest the Hulberts for holding edgy signs the lieutenant governor doesn’t like, they can arrest anybody.”

In their original lawsuit the Hulberts asked for attorneys’ fees, unspecified damages and a judge’s order protecting their right to assemble and protest.