It took years and years, but city leaders in Annapolis, Maryland, have taken over as the owners and stewards of the last undeveloped acres of Carr’s and Sparrow’s beaches.

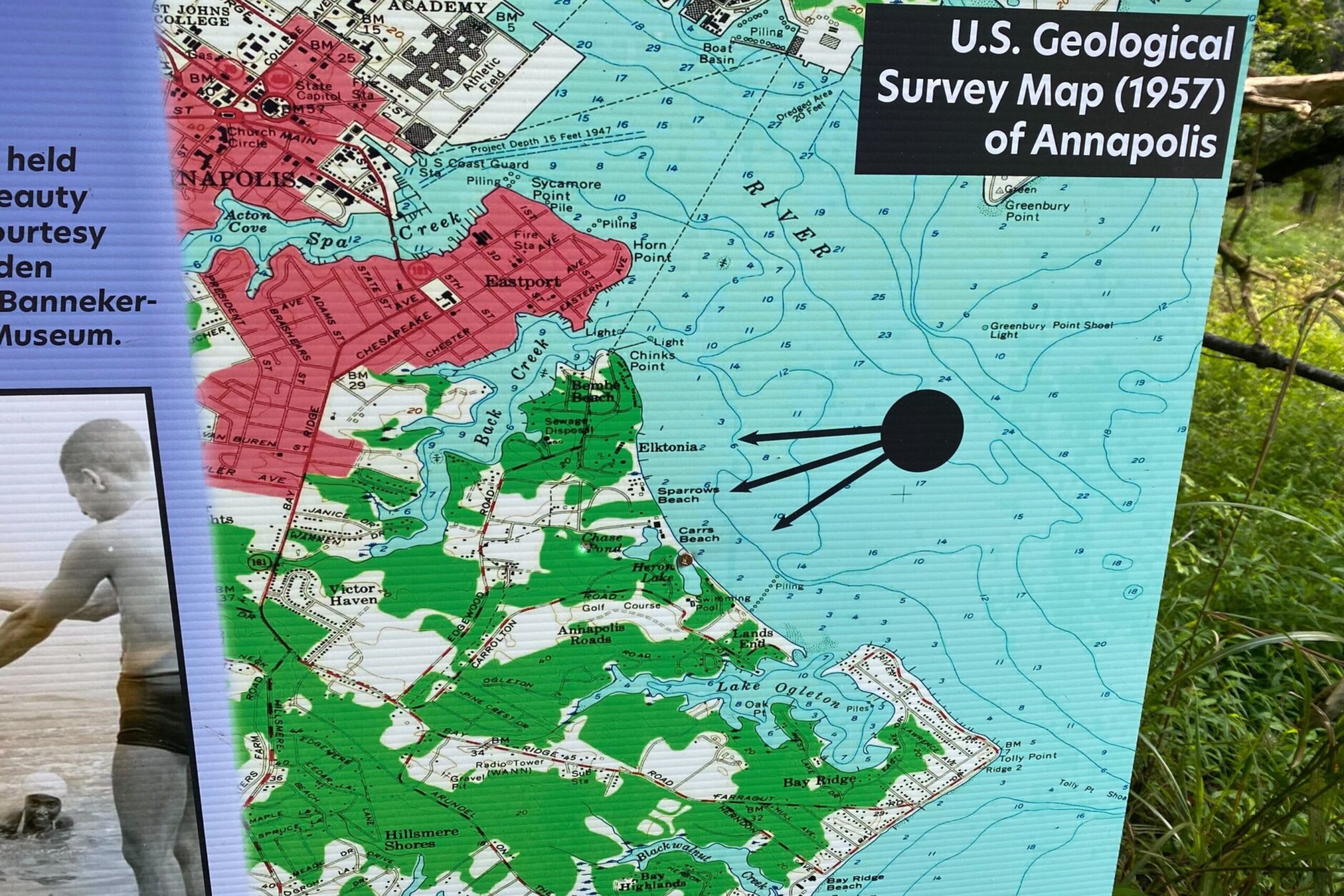

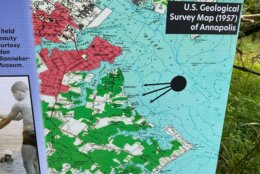

Decades ago, when segregation was still the rule, these beaches were accessible to anyone, and Black Americans from all over the east coast would come vacation here. All-time greats such as James Brown, Duke Ellington and the Temptations would perform at the privately owned resort, too.

Later, the owners would be driven to sell what Anne Arundel County didn’t take by eminent domain, turning Carr’s Beach into a distant memory. Now, the goal is to bring those memories back to life.

“For a young kid coming straight out of east Baltimore it was fabulous,” said Vince Leggett, of Blacks of the Chesapeake, on Friday. He helped lead the effort to keep the last few acres of Carr’s Beach open. “To see the Chesapeake Bay, to see the boats, Ferris wheels, to hear music, to smell the salt air, the seagulls, fish frying, people playing cards — it was a vacation and for people coming out of the city this was a major to do.”

At its peak, the beach was 180 acres; much of that has been taken over by a gated community and a wastewater treatment plant. A path has been created to bring people from Bemble Beach Road and the nearby Annapolis Maritime Museum Park to the last five undisturbed acres along the shores of the Chesapeake. Getting the land to make that happen has been a priority for both the City of Annapolis and the State of Maryland.

“We threatened to buy it ourselves,” said Lt. Gov. Boyd Rutherford. “There was some foot-dragging. We were going to buy it and donate it to the city.” Ultimately, it never came to that.

Rutherford also spoke of the history of the beach, noting that his mother used to visit here before he was born.

“My mother came here when she was younger in the late 1940s. Other family members came down here for the entertainment,” said Rutherford. “That was a time when there were very few places, particularly in beach areas — at a time when folks didn’t have air conditioning either — to be able to come to an area that was a little cooler. So it was important to me, and given that this was the last section, the last area that could be preserved for that beach I felt was extremely important.”

“This place was respite from racial segregation,” said Annapolis Mayor Gavin Buckley. “This is, for me, a sacred spot that simultaneously hearkens to the disgusting era of Jim Crow segregation in America. But also the home of the beautiful sounds of soul, jazz, and R&B music. On these sandy shores, African Americans, despite racist policies and segregation, were able to create something brave, beautiful and meaningful.”

The signing ceremony that made the transition official is something Anne Arundel County Executive Steuart Pittman said was a long time coming.

“When you look up at these trees and you think about the history that they have seen, it’s pretty moving,” said Pittman. “You notice people are drawn to places like this. People come to places like this to congregate because it makes us feel good.”

Leggett said he’s envisioning the creation of something of a living museum, where people can see the past come back to life.

“How do we connect those memories to the actual space?,” he said. “Even though it may be five acres in itself, it’s going to play like it’s 50,000 acres by using technology, for education, and just the best practices to continue to amplify these stories.

“This is where the funk was, right here,” he added.

“Today we move Annapolis forward,” said Buckley. “We are now caretakers of this historic property. We continue to tell the story of what happened here and we will help write the next chapter of this historic place.”

Or, as Leggett told the scores of people who gathered for the signing, “commencement is not the end; commencement is the beginning.”