It’s insane — and telling — that it took this long for a Harriet Tubman biopic.

Too often, women of color are asked to take a back seat to history, even when their lives are heroic enough to earn consideration for their face on the $20 bill.

This weekend, the historical legacy at long last meets the cultural moment in “Harriet,” a rousing piece of work that, while traditionally structured, washes over us with such emotional resonance that it creates an almost religious experience. This isn’t filmmaking, this is moviemaking, as if “movie” were a verb, moving us.

The film opens with Harriet (Cynthia Erivo) under her slave name Minty on a plantation in Dorchester County, Maryland. Upon marrying free black man John Tubman in 1844, her children are supposed to be freed under a manumit deal with plantation master Anthony Thompson. However, when Thompson dies, Minty’s owner Gideon Brodess scraps the agreement and keeps her enslaved.

Facing lifelong bondage, she decides to make a break for it, escaping on a solo journey north to Philadelphia. But freedom for herself isn’t enough, doubling back repeatedly to save her family and others as the most successful conductor of the Underground Railroad.

Ultimately, she becomes the first woman in U.S. history to lead an armed military raid at Combahee Ferry, liberating more than 700 slaves.

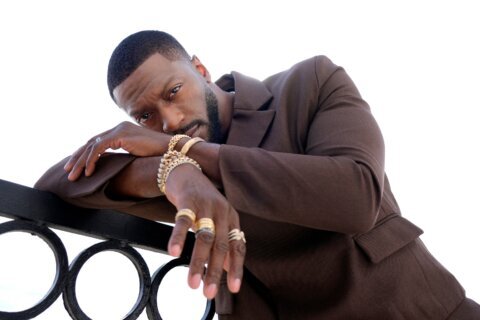

The cast here is superb, including Leslie Odom Jr. (“Hamilton”) as Underground Railroad chief William Still; Joe Alwyn (“The Favourite”) as sadistic plantation owner Gideon Brodess; Jennifer Nettles of Sugarland as Gideon’s wife Eliza; Clarke Peters (“The Wire”) as Harriet’s father, blindfolded so he can claim he hasn’t seen her; Vanessa Bell Calloway (“Coming to America”) as Harriet’s loving mother; Zackary Momoh (“Seven Seconds”) as Harriet’s conflicted husband John; and Janelle Monáe (“Hidden Figures”) as freed Philadelphian Marie Buchanon.

Still, this one all comes down to the one-woman-show of Cynthia Erivo, who continues her phenomenal transition from Broadway to Hollywood. She gained fame for her Tony-winning role as Celie in the Broadway revival of “The Color Purple” (2013), then moved to film in the ensembles of Steve McQueen’s “Widows” (2018) and Drew Goddard’s “Bad Times at the El Royale” (2018).

Now, her face will forever be synonymous with Harriet Tubman, etched into the minds of school children who watch it in their classrooms. Some critics have scoffed that Erivo is a more “sexualized” version than the tough Tubman on postage stamps. To this I say: How many times do male leads get asked such questions? Was Abraham Lincoln really as dapper as Daniel Day-Lewis? Was Malcolm X as handsome as Denzel Washington? Let the sexist questions die.

Erivo’s performance is the epitome of empathetic: soulful, gutsy and commanding the screen. Not only does she embody the rugged survivor who can hoof it upriver and through the woods, she softens as a loving mother, wife and daughter in quiet family moments. Most importantly, she believably portrays bouts of seizures caused by a severe head injury as a teenager when a plantation staffer threw a metal weight at a fellow slave and accidentally struck her in the head.

This causes Tubman to occasionally fall unconscious with temporal lobe epilepsy, causing her to have visions and premonitions, which she interprets as signs from God. Some critics argue that her story didn’t need to be embellished as a divine prophet, but it’s true to the woman in real life, a devout Christian who claimed God told her to go left at a crossroads to avoid a search party to the right.

She was quite literally called “Moses” on wanted posters, building to an Exodus-style river crossing that will give you goose bumps. Similar Biblical themes were also explored in the Nat Turner biopic “The Birth of a Nation” (2016), a masterful Sundance champ sunk by sexual allegations from director Nate Parker’s past. In that light, perhaps it’s fitting that “Harriet” be the film to carry that mantle, for if there ever were an oppressed figure in history, it’s the African American woman.

Only a black woman could tell this story — and writer/director Kasi Lemmons is precisely the one to do it. After playing Clarice’s FBI sidekick in “The Silence of the Lambs” (1991), Lemmons moved behind the camera to direct “Eve’s Bayou” (1997), starring Jurnee Smollett-Bell, Samuel L. Jackson, Lynn Whitfield and Diahann Carroll. More recently, she adapted Langston Hughes’ “Black Nativity” (2013), starring Forest Whitaker, Angela Bassett and Jennifer Hudson.

In “Harriet,” she rewrites a script by Gregory Allen Howard (“Remember the Titans”), showing that the real horror of slavery isn’t merely the whippings, but the breaking up of families. This adds a universality that hits audiences right in the gut. While countless other slave dramas (“12 Years a Slave”) build to the slave’s freedom at the climax, “Harriet” places her freedom at the midpoint, showing the selflessness it took to go back and save others for the second half of the film.

Lemmons also smartly gives her villains motives, showing the plantation owners’ economic dependence on this vile industry. In one scene in particular, Nettles shouts that runaway slaves could cost them a quarter of their total investment. Of course, we the audience know that they’re evil for their lack of basic humanity, but as a screenwriter, it’s important to assign your antagonists actual motives.

If there’s any flaw it’s that the whole project feels a little too tidy, namely a contrived final showdown between Tubman and Brodess like Mel Gibson vs. Jason Isaacs in “The Patriot” (2000). While the concept of their showdown is forced, the way it unfolds is admirable, taking the high road with a chilling prediction of the Civil War. Cue a Union Army epilogue that feels tacked on (Lemmons said it was longer in the script but had to be cut due to budget).

Such minor flaws are overshadowed by the fact that it’s about time we saw a black female lead in a historical role, written by a black woman and directed by a black woman. That’s not to diminish the contributions of cinematographer John Toll (“Braveheart”) and composer Terence Blanchard (“BlacKkKlansman”), but it’s important that the lead singular vision come from a rooted place of authenticity.

Is “Harriet” cinematically groundbreaking? No. Is it narratively formulaic? Yes. But is it important for this moment in time? Absolutely. Like “Green Book” last year, “Harriet” received a standing ovation at the Middleburg Film Festival. Unlike “Green Book,” its writer and director actually reflect the faces on screen. It’s probably too safe to win Best Picture, but I hope it’s at least nominated as a feel-good, necessary entry point to one of the most important lives in U.S. history.