By Jacob Bell

Capital News Service

BALTIMORE — Swimming through the 2.2 million gallons of water at the National Aquarium are more than 500 species of fish, including sharks, rays and eels. And whether the animals glide, float, slither or dart, they all poop.

They poop a lot.

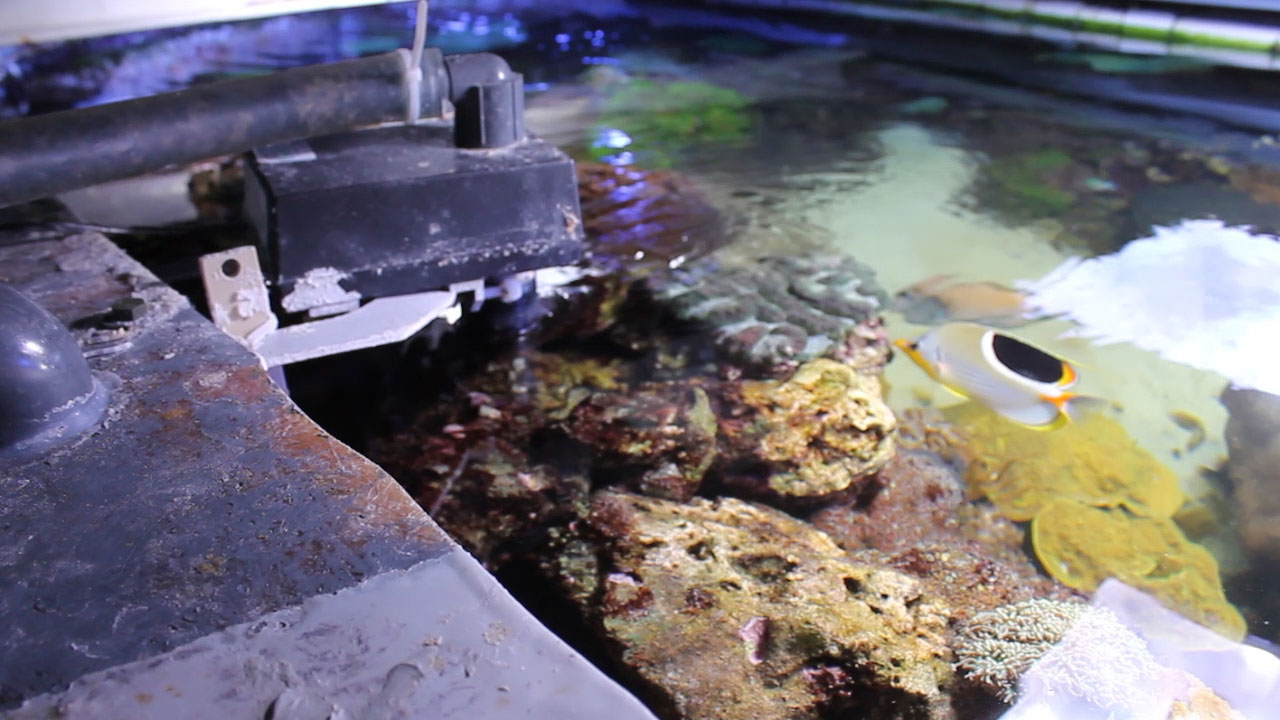

To deal with that poop, as well as the accumulation of bacteria, algae and harmful chemicals, the aquarium employs full-time staff to physically vacuum and scrub its various tanks. Often the cleaning is done outside of the public view — conducted either behind the scenes or before the aquarium opens.

“It is a major undertaking to not only keep the exhibits clean, but to keep the animals healthy,” said Jay Bradley, curator of fishes at the National Aquarium. “It does depend on the exhibit how often things are done, but there’s something being worked on every day.”

In the aquarium’s Blacktip Reef, SCUBA-clad aquarists make dives almost daily to clean tank glass or power wash portions of the exhibit’s more than 3,000 pieces of faux coral, according to Bradley. Divers use specialized pads and bleaching equipment to eliminate algae, and small tools to collect waste in narrow crevices.

They also must maneuver around 65 species of sharks, rays, sea turtles and Indo-Pacific fish.

And in both the Blacktip Reef and the Living Seashores exhibits, staff use hydro-vacuums to suck up organic waste like poop and uneaten food from the tanks’ sandy bottoms. If left untreated, organic waste can break down into chemicals that are toxic to fish, such as ammonia or nitrite.

“There are a lot of different processes involved; there are protein skimmers, there are biofilters,” Bradley said. “(W) e’re also maintaining the life support elements and cleaning those as well.”

Last year, the aquarium spent $8.7 million — more than 18 percent of its total yearly expenses — on facility operations and marine life support, according to its 2014 annual report. It also spent more than $18 million on salaries and benefits for its 450-person staff, 50 to 70 of whom have some role in keeping exhibits clean, said Andy Aiken, director of life support for the National Aquarium.

Life support elements include the filtration, temperature, light and treatment systems used to safeguard water quality throughout the aquarium. The systems are tied into a centralized computer network, which, while capable of making some adjustments to the various exhibits, mostly flags when water quality is out of balance in terms of acidity, salinity or toxicity, according to Aiken.

“The life support system parameters really tell us how the system is operating, but its effectiveness is measured by water quality,” Aiken said. “Water quality tests are taken frequently. Some systems every day, other systems that are more stable maybe once a month.”

The tests measure factors like pH or ammonia levels, allowing staff to make adjustments to the aquarium’s three-part, biological, chemical and mechanical filtration system if necessary.

In biological filtration, bacteria living on exhibit surfaces or in chambers called “bioballs” convert chemicals formed from the breakdown of fish food and poop into less hazardous byproducts, according to a 2012 report from the Education Department at the National Aquarium.

Some of those byproducts are removed through mechanical filtration, during which water from the tanks passes over a bed of coarse gravel and sand that traps waste particles.

Any unwanted chemicals remaining in the tank after mechanical filtration undergo chemical filtration via carbon filters and surface skimmers. Hydro-vacuuming is part of chemical filtration as well.

Aquarium staff also adjust temperature and light in aquatic exhibits, as well as land-based ones like the Upland Tropical Rainforest or Australia: Wild Extremes, to mirror the conditions the animals would face in the wild.

The Pacific Coral Reef exhibit, for example, has programmed sunrise and sunsets, and the wavelength of light used allows for the growth of seaweed and algae that jellyfish in the exhibit rely on for food, according to the 2012 report.

In addition to staff, a team of divers from the aquarium’s nearly 950 volunteers assists with tank upkeep. In-water cleaning is more intrusive, according to Bradley, but the animals’ reactions often vary depending on the species and how comfortable they are with the process.

“Most of the time they’re pretty tolerant of the things we’re going in there to do,” Bradley said. “A lot of the times they’ll get a little startled, maybe (act like) ‘whoa, what’s going on,’ but then they’ll usually get used to it and settle back down and not have much trouble with it.”