Invoking Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s own words, Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam announced Thursday that the statue of Lee would be removed from Monument Avenue in Richmond.

“In Virginia, we no longer practice a false version of history,” Northam said, ordering the statue removed “as soon as possible.”

The governor said there will be “discussions” about what to do with the statue and the pedestal.

The Lee statue is one of five Confederate monuments along Monument Avenue, a prestigious residential street and National Historic Landmark district in Virginia’s capital.

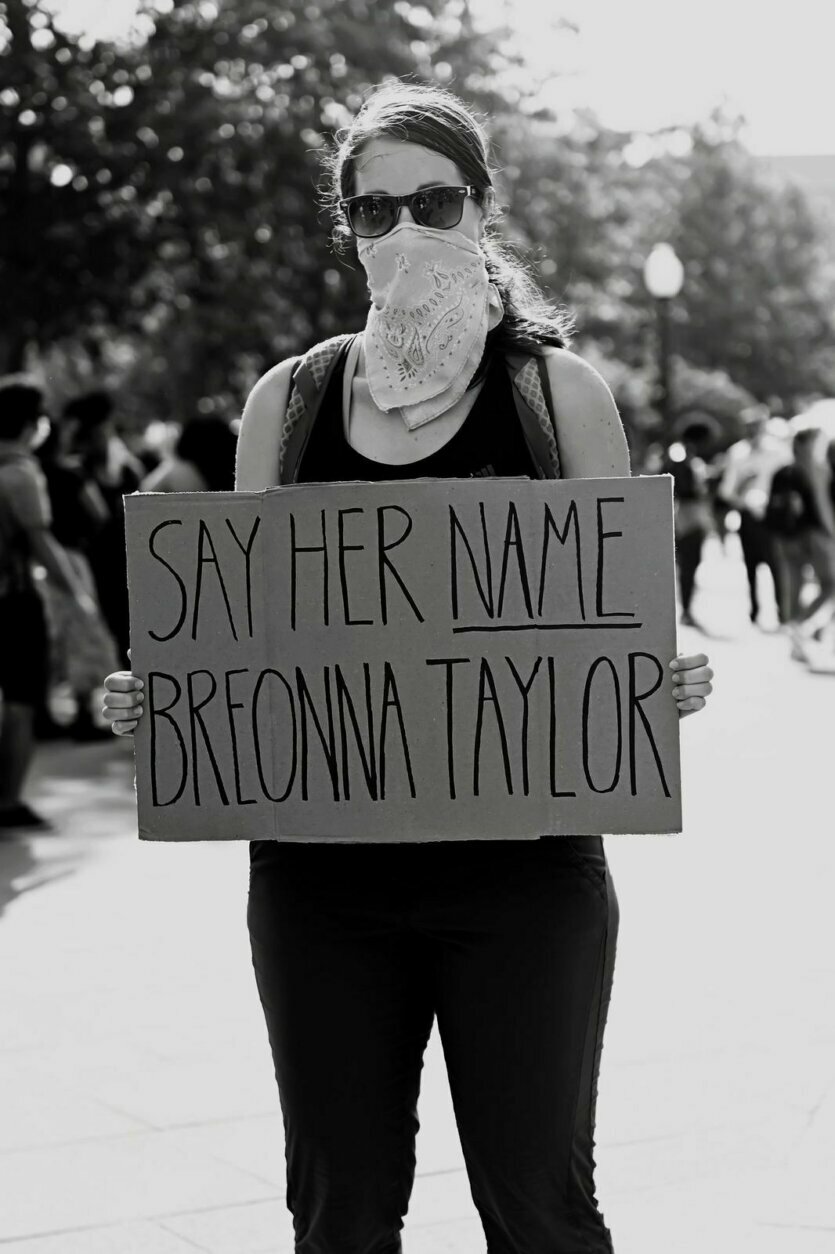

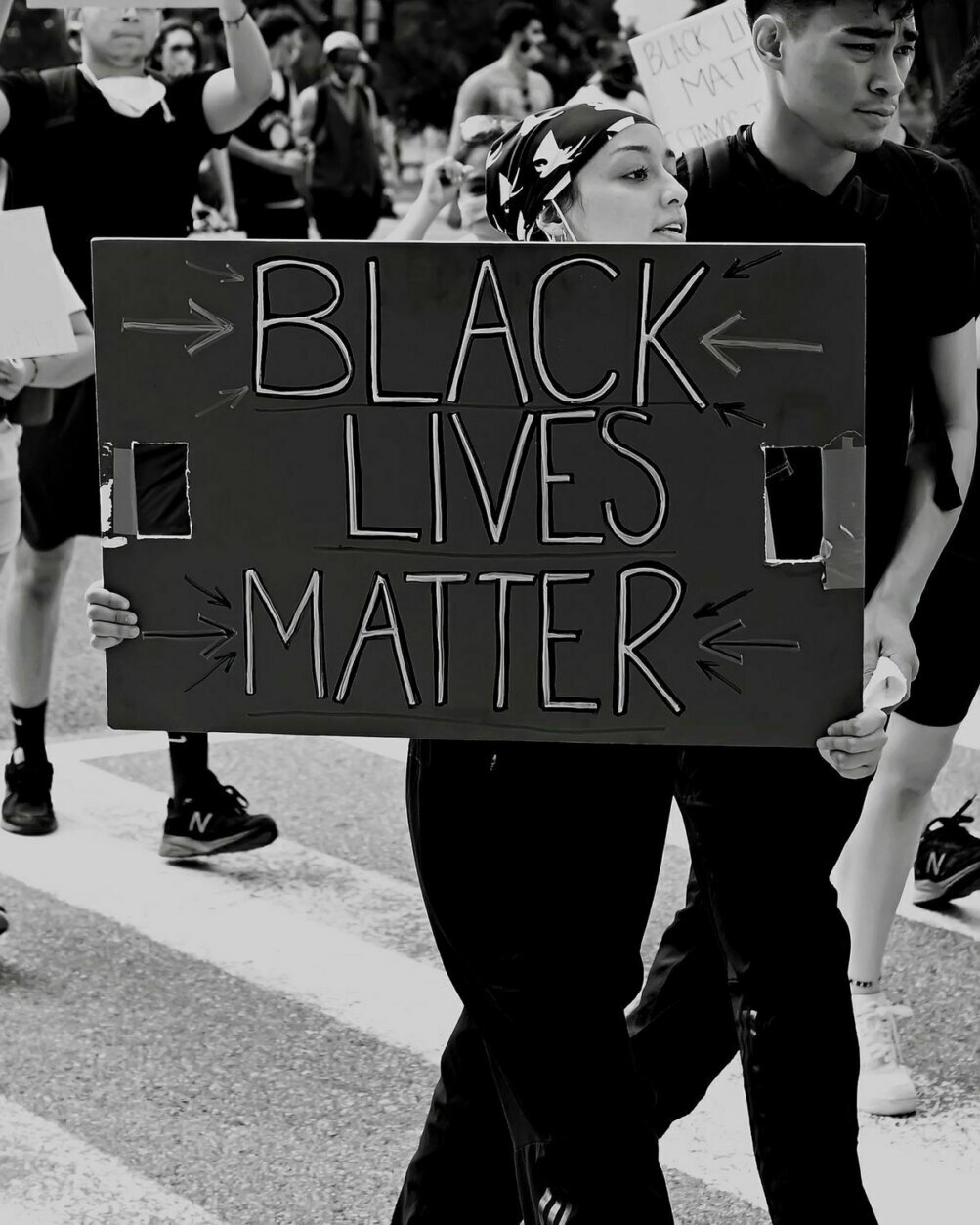

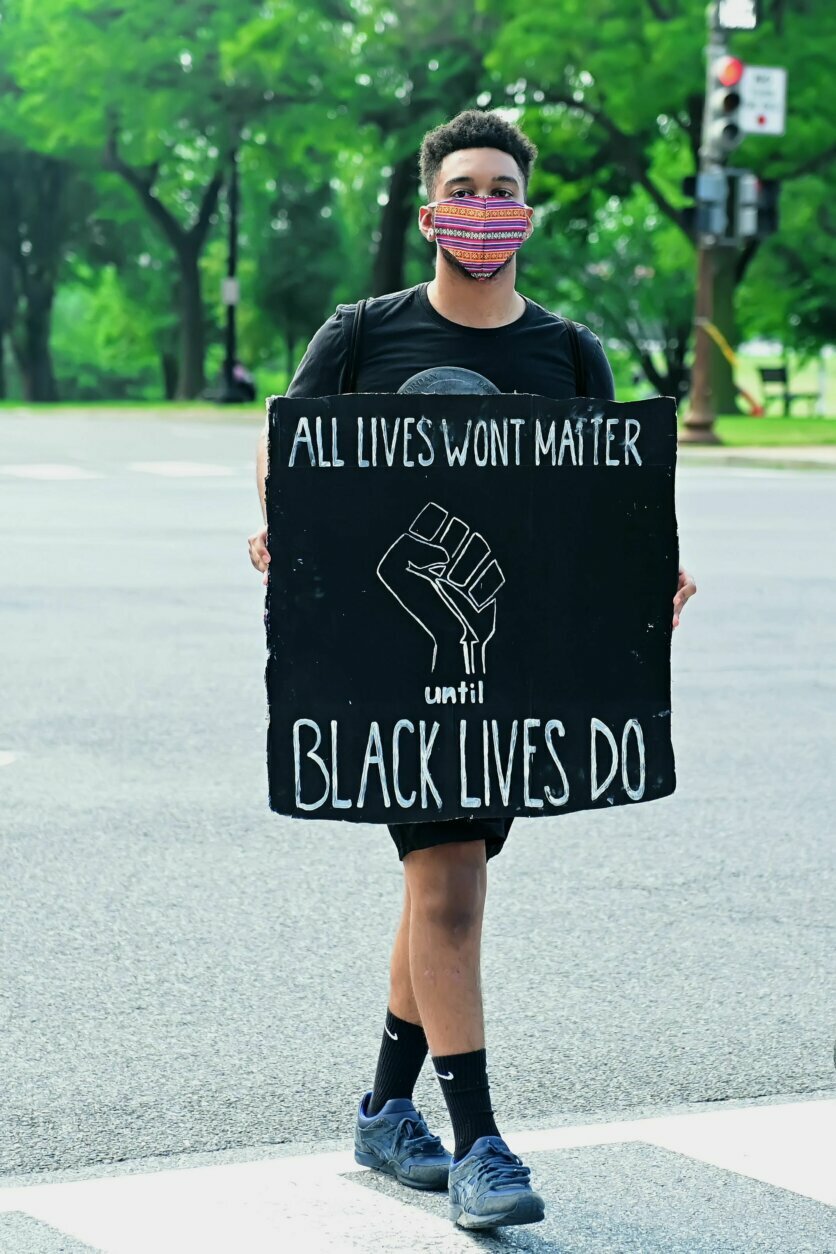

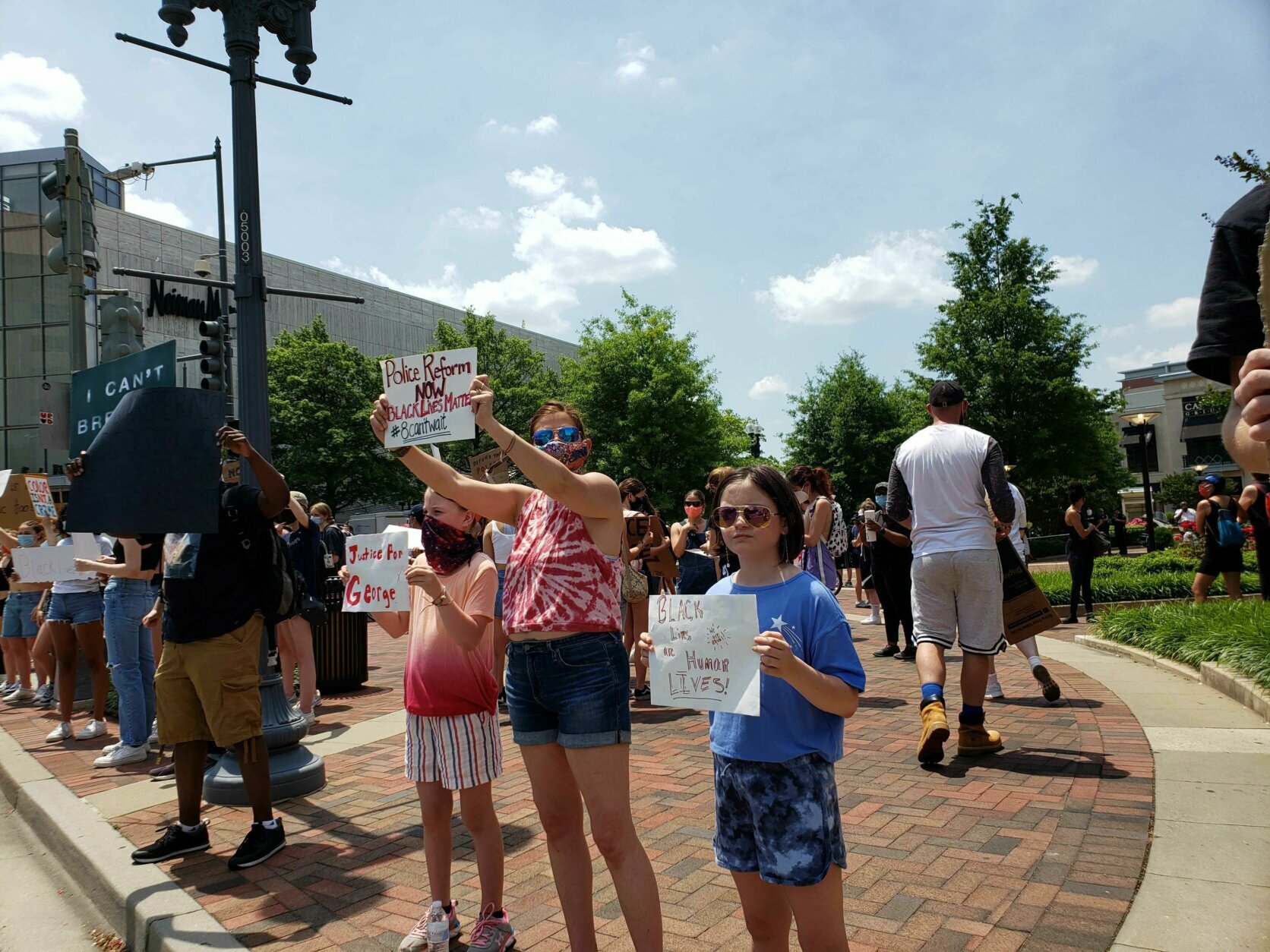

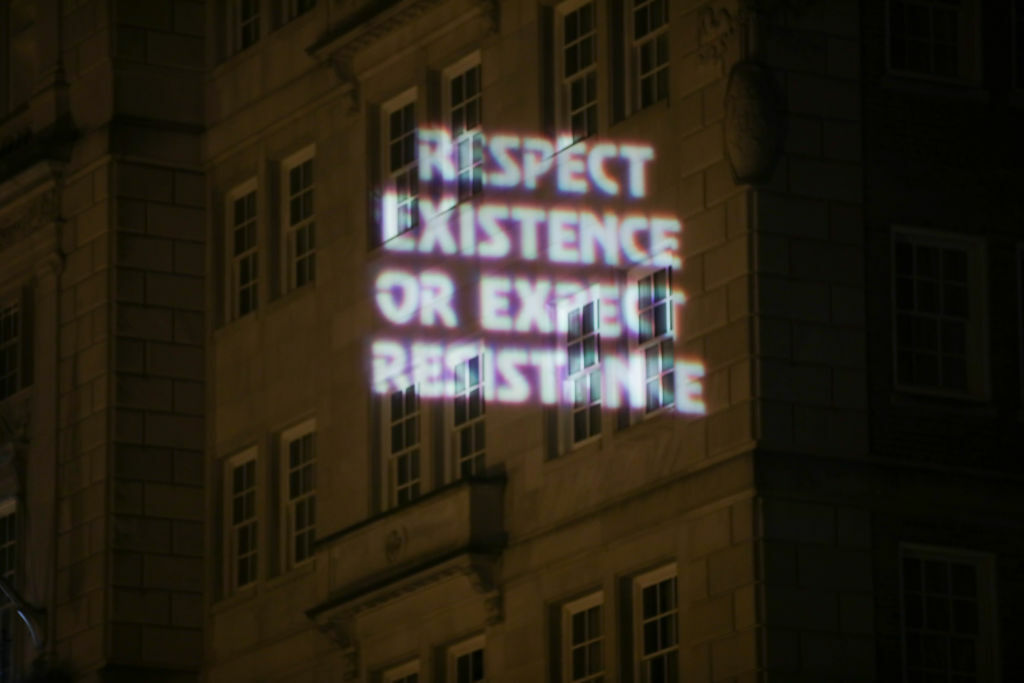

Monuments along the avenue have been rallying points during protests in recent days over the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police last week, and they have been tagged with graffiti, including messages that say “end police brutality” and “stop white supremacy.”

Asked “Why now?,” Northam replied, “It’s pretty apparent.”

Lee’s words

The governor said, “Lee himself didn’t want a monument, but Virginia built him one anyway.”

Northam quoted Lee’s words: “I think it wise not to keep open the sores of war, but to follow the example of those nations who endeavor to obliterate the marks of civil strife.”

But “Virginia leaders said, ‘We know better,’” Northam said. The erection of the statue in 1890 was just part of “a new campaign to undo the results of the Civil War by other means,” which included new laws, including limits on the right to vote, which cut the number of registered black voters by 90%.

“We put things on pedestals when we want people to look up,” Northam said. “Think of the message this sends.”

Saying that the six-story monument towers over its surroundings, the governor added, “When a young child looks up and sees something that big and prominent, she knows that it must be important. And when it’s the biggest thing around, it sends a clear message: ‘This is what we value the most.’ But that’s just not true anymore.”

He called the honoring of Lee an aspect of the “false version of history” that claims the Civil War was about states’ rights rather than slavery.

“No one believes that any longer,” Northam said.

‘It’s time’

A chorus of Virginians, including elected officials and activist citizens, echoed Northam’s words.

“Ladies and gentlemen, it’s time,” said Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney, introducing Northam. “It’s time to put an end to the Lost Cause and fully embrace the righteous cause.”

He added, “Richmond is no longer the capital of the Confederacy.”

Zyahna Bryant, who wrote the first petition in 2016 calling for the removal of the Lee statue in Charlottesville, called for more of the kind of activism that had brought the Richmond statue down.

“Without a little bit of making people uncomfortable,” she said, “we wouldn’t be here.”

Bryant concluded by saying, “Black lives matter.”

Rev. Robert W. Lee IV, great-great-grandnephew of the Confederate general, said that “Today the world is watching” because of the protests surrounding Floyd’s death.

“If today is not the right time, when will it be the right time?”

During the announcement, Lt. Gov. Justin Fairfax said, “This is the first day of the next 400 years.”

He called conditions such as substandard schools and housing, and inequities in health and criminal justice, “shrines of an ideology of inferiority” that constituted “more Confederate monuments.”

Fairfax added, “There is so much more work to be done.” And he concluded, “America has its best days ahead of us because of what we’re doing right now.”

Attorney General Mark Herring called the Lee memorial “a grandiose monument honoring a racist insurrection.”

The way we explain our history, he said, influences “the way each of us view our role in our society.” He added, “How do you possibly explain these statues to a black child? … You can’t.”

Sen. Mark Warner, D-Va., a former governor of Virginia, was asked about the decision to bring down the statue during a conference call with reporters. “I think it’s time,” he said, noting the moment and that there was local support in Richmond for the decision.

Northam seemed to refer to his blackface scandal from last year, answering a question about his process toward making Thursday’s order, saying he had spent a lot of time “listening and learning.”

He encouraged all Virginians to do so, as one of the steps the commonwealth could take moving forward.

A movement

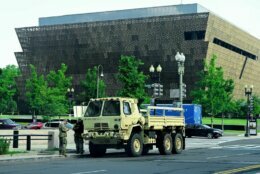

Confederate memorials began coming down after a white supremacist killed nine black people at a Bible study in a church in South Carolina in 2015, and then again after a violent rally of white supremacists in Charlottesville in 2017.

Word got out Wednesday that Northam would announce the removal. The same day, Stoney announced plans to seek the removal of the other Confederate monuments along Monument Avenue, which include statues of Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Gens. Stonewall Jackson and J.E.B. Stuart. Those statues sit on city land, unlike the Lee statue, which is on state property.

Stoney said he would introduce an ordinance July 1 to have the statues removed. That’s when a new law goes into effect, which was signed earlier this year by Northam, that undoes an existing state law protecting Confederate monuments and instead lets local governments decide their fate.

The monument-removal plans drew criticism Wednesday from the Virginia Division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans.

Republican state Sen. Amanda Chase, who is running for governor, has started a petition on her campaign website to save the statues, claiming, “The radical left will not be satisfied until all white people are purged from our history books.”

Joseph Rogers, a descendant of enslaved people and an organizer with the Virginia Defenders for Freedom, Justice & Equality, said Wednesday at a rally near the Lee Monument that he felt like the voices of black people are finally being heard.

“I am proud to be black, proud to be Southern, proud to be here right now,” Rogers said.

WTOP’s Mitchell Miller and The Associated Press contributed to this report.