WASHINGTON — It’s been a rough spring for baseball. Cold fronts and storms have pounded the east coast and Midwest, bringing unseasonably winter-like conditions to the first couple weeks of the baseball season. Unsurprisingly, people have not turned out at the ballpark in droves.

That’s certainly been true in Baltimore, where Camden Yards saw its lowest attendance in the history of the ballpark last week. The Orioles drew just 7,915 fans for a Monday night tilt against the division rival Toronto Blue Jays.

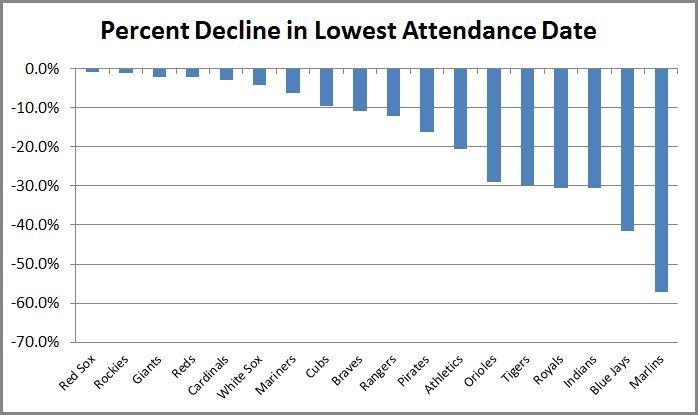

As Yahoo’s Jeff Passan pointed out Monday, attendance is down across the league about 10 percent so far. Dips in average attendance are troubling, but they don’t tell the bigger story, the one that should concern every front office across the league. That is the drop in the minimum attendance, the worst number that each team posts every season.

Why is this important, and potentially a larger sign of endemic issues in the game? Because the lowest draw of the season essentially represents a game with zero walk-up crowd, meaning the number of tickets sold — the paid attendance number that each team reports — is essentially equal to a team’s full season ticket holder base. If that number is down, you can reasonably assume season ticket sales are down as well.

Through April 9, roughly 10 games into each team’s season, 15 of the 30 teams in Major League Baseball had already posted a single-game low attendance mark lower than the worst date in 2017. Let me say that again: In the first week-and-a-half of the season, half the league had already drawn fewer fans to one of their games than in any game the year prior.

(A quick note: Past figures don’t count anomalies, like the Pirates-Cardinals game in Williamsport or the Astros-Rangers series moved to Tampa during Hurricane Harvey.)

Sure, the Miami Marlins have never been a huge draw. But their lowest attendance date last season was 14,390, on Sept. 6 against the Nats, their only sub-15,000 person night of the year. On their last homestand, the Marlins drew 7,003 fans or less in four of their six games, bottoming out at 6,150. You can chalk that up to a change in attendance reporting policy, but that only covers one team.

The Oakland A’s cracked 10,000 fans only once in their four-game set against Texas Apr. 2-5, drawing just 34,613 for the entire series. The Athletics’ lowest mark last year was 9,329 on a late September Monday against the Mariners when they were well out of contention. They’ve drawn worse than that four times already this year.

What’s perhaps most troubling, though, is that the 15 teams in question are not all obvious candidates for poor draws. They include teams from big markets (Red Sox) and small (Indians), from traditionally strong markets (Giants/Cardinals) and those who have struggled in recent years (Pirates/Royals). The Cubs joined the list this week (along with the Braves and Mariners, bringing the total to 18 teams), drawing just 29,775 for a Friday night game against Atlanta. The lowest number at Wrigley Field in 2017: 32,905.

Ten teams have already hosted a game with a paid attendance drop of 10 percent or more from their worst date last year.

MLB confirmed to WTOP that nothing has changed in their general practices of counting attendance numbers since the league offices merged two decades ago. Discussions with ticket offices around baseball did not indicate that any substantial change has taken place in the way season ticket packages are sold — for instance, partial plans replacing full-season plans, perhaps leading to specific dead dates on the calendar.

This is disconcerting not just from a revenue standpoint, but much more significantly from a fan experience perspective. Empty stadiums may give you a better shot at taking home a foul ball, but they’re hardly the ideal setting to watch a game. When players, fans and broadcasters about regular season games having a postseason vibe, they mean the buzz and electricity that come from a packed stadium. Poorly attended games make for a diminished ambiance. With ticket and concession prices ever increasing, there is a danger of a downward spiral of return on fan investment.

Yes, the weather will warm up eventually, and with it the walk-up crowds that make for fuller stadiums once school lets out for the summer. But that’s not necessarily a saving grace for the teams not even making an effort to compete this year, especially once the school year starts again in August. The Tampa Bay Rays — not one of the 18 teams mentioned above — posted their worst three dates of 2017 from Aug. 23 on. What will happen to the teams well out of contention come the dog days?

Whatever the ceiling may prove to be, it is clear that the floor has fallen. We may not know the true fallout until the end of the season.