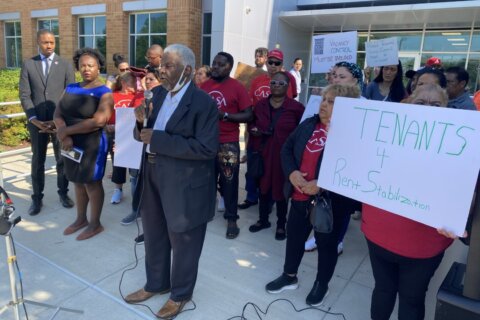

The issue of rent stabilization is back in the news this week after the Prince George’s County Council introduced a bill that is similar in structure to the one in Montgomery County. But even before it was formally introduced, progressives on the council were balking at some of the proposals, saying they don’t go far enough to help the county’s seniors and low-income families stay in their homes.

The issue has been debated in the county for more than a year, so much so that a temporary cap passed last year had to be extended because of disagreements about what permanent rent stabilization would look like.

But some in the county are also worried that even the temporary caps were enough to scare off developers, slowing efforts to build more housing in a region where it’s so badly needed.

The point was made this week by the Maryland Building Industry Association, which noted that while Prince George’s County has 23% of the D.C. area’s close-in population, only 16% of the new apartment buildings that either broke ground or got the final permits needed to do so are being built in the county. It’s three projects — two which relied on government subsidies and one that got funding from Amazon, according to Brian Anleu, with the Apartment and Office Building Association.

“What we’re actually seeing is that Montgomery and Prince George’s seem to be falling behind other jurisdictions,” Anleu warned. He said higher construction costs and inflation play a role in the construction slow down. But he argued that, since last year, the rent caps in place in both jurisdictions are also playing a role.

“Some of this is obviously attributable to the regulatory environment in those two counties,” said Anleu. “Specifically things like rent regulations, landlord tenant regulations, other things that discourages investments in those jurisdictions. But absolutely, interest rates, labor costs, inflation — it’s all having an impact.”

But some on the council are skeptical of those claims, including Council member Krystal Oriadha, who is pushing for even stricter measures to limit the ability of landlords to increase rents.

“The sky is always going to be falling within any industry when we have any conversation,” said Oriadha.

“If we listen to the industry that wants no regulation at all, we’ve already seen the consequences,” she added, referring to exorbitant rent increases in 2022 and 2023 that led to the council passing temporary caps last year. “It was birthed out of the reality of $200, $400, $800 increases. … They created the problem that now needs to be addressed.”

Council Chair Jolene Ivey, who helped lead the push for the temporary caps last year, is now warning against pushing too aggressively.

“The only multifamily housing that’s been built, or that we’re getting permits for, are for things that take government money to subsidize,” Ivey said. “We can’t afford to continue to do that. We need to have the industry to come build market rate housing out of their own pockets. Right now, we have to subsidize everything, because we can’t draw in investment otherwise.”

According to the Prince George’s County Multi-Family Rental Affordability Dashboard, 803 total apartment units are considered to be “in the pipeline,” which includes projects that haven’t gotten final approval yet. Of those 803 units, only 30 apartments — part of a 158 unit development in Capitol Heights — are market rate.

The slow down in construction is also impacting tax revenues in both Prince George’s and Montgomery, where the MBIA says transfer and recordation tax revenues are seeing substantial declines. The industry argues that’s unique to those two counties.

“Right now, Montgomery and Prince George’s County are not providing the best rate of return because of the regulatory environment,” warned Anleu. “The capital is going to go to where you’re going to get a better rate of return. And right now, that’s Northern Virginia.”

He said long term, that will only lead to more problems.

“We need housing at all levels, including market rate, including what some people label as ‘luxury housing,'” Anleu said. “The reality is when you build housing at those price points, it opens up housing for other people downstream. In other words, if I’m someone who can generally afford to live in what you might call ‘luxury housing’, but there isn’t enough luxury housing to meet my needs, then I’m going to find housing at a lower price point. So now I’m competing with people who have less means than I do for housing that they can afford.”

Oriadha said it’s too late for that.

“The reality is that currently, right now, we have residents who can’t afford what’s happening,” she said. “So what happens to them? Let’s say we don’t do anything for the hope of new housing that people also can’t afford? And then the current housing that people cannot afford?”

She said the current caps are keeping people in their homes. She plans to submit her own bill this month to address rent spikes.

“We have to also think about the residents that are currently here,” she added. “That’s a responsibility. I want to be forward thinking about development but what am I going to say to the residents that live here right now?”

Get breaking news and daily headlines delivered to your email inbox by signing up here.

© 2024 WTOP. All Rights Reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.