This is the third part in WTOP’s “Bad Brains” special report examining brain injuries in football, what doctors know about them and what’s being done to make the game safer.

COLUMBIA, Md. — The race to create a safe football helmet is big business, but it’s also something of an oxymoron. A football helmet was never designed to be “safe,” at least not from brain injury. That goes for the first generation of polymer helmets in the 1950s, and doubly so for the old leather helmets introduced back in the 1920s.

“Helmets were initially made and studied to prevent skull fractures, prevent bleeding around the brain, and certainly are effective for that,” said Dr. Stacy Suskauer, a brain injury specialist at Kennedy Krieger Institute.

Helmet technology has come a long way in the intervening decades, but the device remains, first and foremost, to prevent catastrophic head injuries, not brain injuries. Helmets have dramatically cut down on skull fractures and facial injuries — not concussions. For those who have used them for years, the delineation is clear.

“I just don’t buy that these things are going to protect you,” said former NFL lineman Scott Peters. “You could put a steel cage around your head and you could still get a concussion, because it’s the deceleration of the brain inside the skull that is causing a lot of this trauma.”

The race for a safer helmet

Companies such as Xenith are outfitting helmets with a floating system of inflatable shock absorbers between the shell and the skull to help reduce force, and attaching the chin strap to that system rather than the helmet itself to cut down on rotational forces.

While these innovations can help mitigate some of the damage of head collision in the sport, Peters will always see the helmet as a last resort, not a reliable safety instrument.

“You want a good air bag in your car, but you don’t want to deploy it every time you drive, right?”

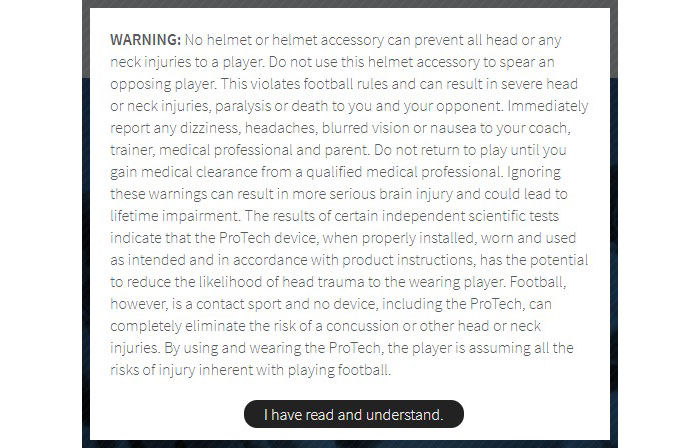

Using that analogy, the ProTech system from Defend Your Head might be analogous to something more like a seat belt. The disclaimer on Defend Your Head’s website is crystal clear that it’s not some sort of magic bullet solution for brain injury in the sport, but the company hopes its product can be part of the solution in making the game safer.

At first blush, ProTech looks like products that you may have seen before in the game. It’s a shell that slides over an existing helmet, almost imperceptibly from afar, and snaps into place. Where it differs is in its chemical composition and the way it attaches to the helmet itself. The polyurethane foam has some give to it, designed to provide shock absorption, and it has the ability to shift slightly upon a rotational hit, deflecting force away from the head. Essentially, it provides a two-pronged line of defense before the helmet itself is even involved.

“We want to reduce force, or reduce the risk of force, before it reaches the hard shell of a helmet,” said Glenn Tilley, CEO of Defend Your Head.

Teams at the high school and college level have been using ProTech in practices over the past couple seasons, helping the company build a database to see how effective the product is at achieving its goals. After working with 25 to 30 teams last year, Defend Your Head added another 60 to 80 for the upcoming season. Clients now include high school powerhouses such as Roman Catholic in Philadelphia, FCS programs like Holy Cross and Dartmouth, and even FBS schools North Carolina State and Penn State.

Eventually, Tilley hopes to see ProTech used at the professional level, but understands the technology will have to prove itself to earn that adoption.

“(We have to) earn our keep, earn our proof of efficacy on the field, and then we will start reaching out to the NFL,” he said.

A significant university study of the ProTech system is expected to be announced later this month, with the first independent testing results in a practice setting. Tilley is excited about the results, knowing how much internal evaluation the product has received.

“Our testing is, I think, comprehensive relative to what the old traditional testing requirements were in general for helmets. … And that’s everything from severity index, to peak acceleration, to lateral hits, rotational hits. We try to test the helmet in all different levels of force, angles and impacts,” he said.

The more teams that use ProTech, the more data the company has to mine as it makes adjustments to its technology.

“Every time we’re on the field of play with a team, it’s a study,” said Tilley.

The potential paradox of better technology

Any new advance in helmet safety technology begs the question of whether the idea of a safer helmet might lead to more potentially dangerous head contact in the sport. The psychological theory is known as risk compensation, something Peters thinks is a very real problem among football players in regards to helmets.

“When somebody thinks that they’re protected, behaviors change,” Peters said.

Dr. Shane Caswell, who studies sport-related concussion issues at George Mason University, is less troubled by the idea that an improved helmet might cause an increase in head contact. But he fears it might result in fewer players making the needed adaptations in technique to remove the head from tackling. He is especially concerned for those teams that practice exclusively using the ProTech, but then don’t use the product in games.

“My concern would be that they’re not going to change their behavior at all,” Caswell said. “And if we know that the incidence of concussion is higher in youth leagues, and in games than in practices, then wearing this in practice — if they don’t change their behavior in a game — I wonder, is it going to be effective at all?”

Advances like the ones Xenith and Defend Your Head have made in helmet technology offer the potential to mitigate some of the unavoidable contact the game of football creates. But they also bring up a lesser-discussed point about how the economics of the game might trickle down to player safety.

Xenith’s youth helmets range up to $285 each, compared to $110 for a basic Riddell youth helmet, or even as little as $60 for a Schutt model. At $149.99, ProTech isn’t a huge financial burden for a team with the resources to invest in it, especially since the product is meant to last five years or more. But when you scale out the difference for teams that can only afford bargain-basement prices without the add-ons, it quickly becomes apparent that wealthier football teams may be better positioned to keep their kids safer.

“You could put a steel cage around your head and you could still get a concussion.”

— Former NFL lineman Scott Peters

Similarly, a 2015-16 study of youth football programs in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine concluded young athletes in poorer communities are less likely to participate in a USA Football league where coaches have completed the Heads Up Football certification. Compounding that with inferior technology could expose children already more vulnerable to poverty-related health risks to a more dangerous version of the game.

“Inadvertently, you may actually be increasing disparity, and it’s something that we need to be mindful of with all interventions when we work with the community,” said Caswell.

Defend Your Head is aware of the financial challenge and has made it a priority to find ways to make its product as accessible as it can.

“We are doing everything we can to get the product on the field, and that’s working to make this as affordable as possible so that young kids and families can afford this,” said Tilley.

Some complications are out of the technology companies’ control, though. There’s also a language barrier issue in discussing safety in some communities, something compounded by the relatively new terminology emerging from the science around brain trauma.

“We know there are large sociocultural challenges with concussions,” said Caswell. “In the Spanish language, there’s no direct translation for the word concussion.”

As the intersection of technological advances and technique begin to overlap, we may start to finally see what sort of combined, cumulative effect the two have on reducing the impacts that lead to concussions and conditions such as C.T.E. As a former college player himself, Tilley understands that whatever protection ProTech provides, it is just a piece of the larger puzzle, not something that eliminates the need for better technique.

“One should not replace the other,” he said, acknowledging that head trauma will never be completely removed from the game.

“Because the reality is that it’s unavoidable at times to have a collision of head-to-head. So when that happens, you know, how can you reduce the risk? How can you make that a little safer?”

Part I: What’s happening to football’s brains?

Part II: Can better tackling technique make football safer?

Part IV: Can football and its players recover from the concussion crisis?)