WASHINGTON — You’ve probably at some point described something as “deader than disco,” and it’s true that light-up dance floors and white suits for men are pretty rare these days. But Alice Echols would argue that “disco never really went away.”

Echols, a professor at the University of Southern California and the author of “Hot Stuff: Disco and the Remaking of American Culture,” will speak at the Library of Congress May 6. It’s part of their Bibliodiscotheque series of events celebrating and examining what was once the far-and-away most popular music in America, and which seemed to disappear as quickly as it sprung up.

But in her book and in an interview, Echols said that disco continues to influence musical culture and the culture at large. Pointing to acts and songs from Madonna to LCD Soundsystem to Daft Punk all the way up to Lorde’s “Green Light,” released in March, Echols said of disco, “This is music that continues to permeate the pop music universe.”

Three areas of great change

Maybe even more widespread, and lasting, were the “interventions and changes that disco made,” Echols said, especially the way it “broadened the contours” of blackness, femininity and male homosexuality.

Going back to disco’s roots in Philadelphia soul, such as The O’Jays and Harold Melvin and The Blue Notes, and even farther back to Motown, disco, Echols said, was part of the process of “changing and expanding what black artists could do, and the sounds they could produce and be popular with.”

Black musicians and producers were “the architects,” and experimented “with these very lavish, sophisticated arrangements that, to some people, didn’t always sound recognizably soulful, or even black.” That led to a change of attitudes regarding black masculinity, Echols said, from “the sex-machine model of James Brown toward a more seemingly woman-friendly style,” the “love man” style of Barry White.

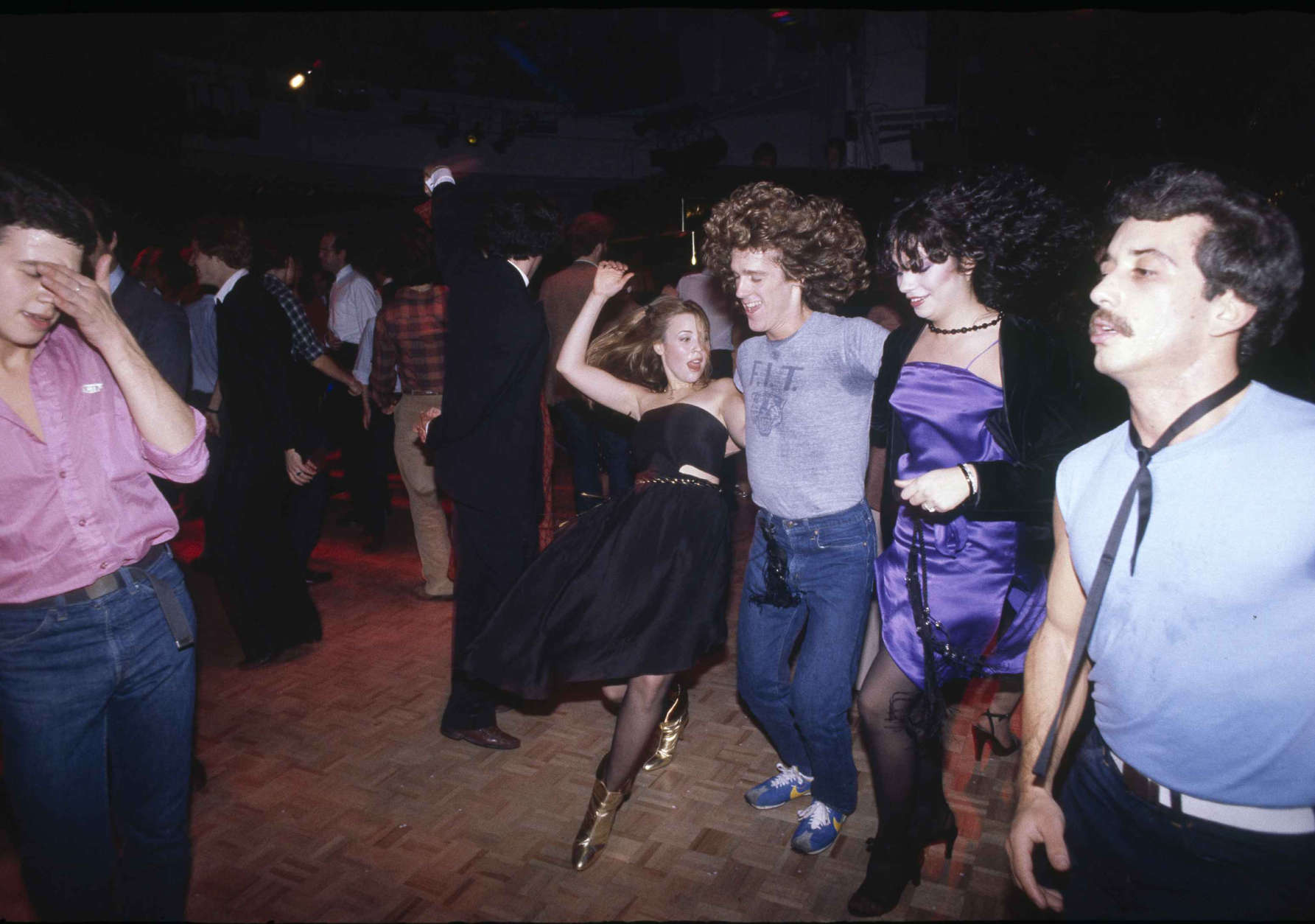

Gay men in the disco heyday of the mid-1970s were redefining what they could be as well, Echols said — flexing not only political but literal muscle. She details in her book how the salad days of disco were a time of energy around gay rights, at the same time redefining what being a gay man meant — and could look like.

A frail effeminacy of style and presentation that reflected the damaged view that mainstream society had of gay men, she said, “gave way to a macho style that would be recognizable to anyone who’s ever seen a photograph of the Village People.”

And lots of disco — in her book, Echols uses Patti LaBelle, Chaka Khan and Donna Summer as examples — reflected a new openness about sexuality, and life, from women, particularly black women, who moved from “representational strategies that were rooted in respectability.”

“You can’t really make sense of how the culture moved from … the white-gloved Diana Ross to Lil Kim in a fairly short period of time, without exploring disco and disco’s role in opening up and validating female sexuality.”

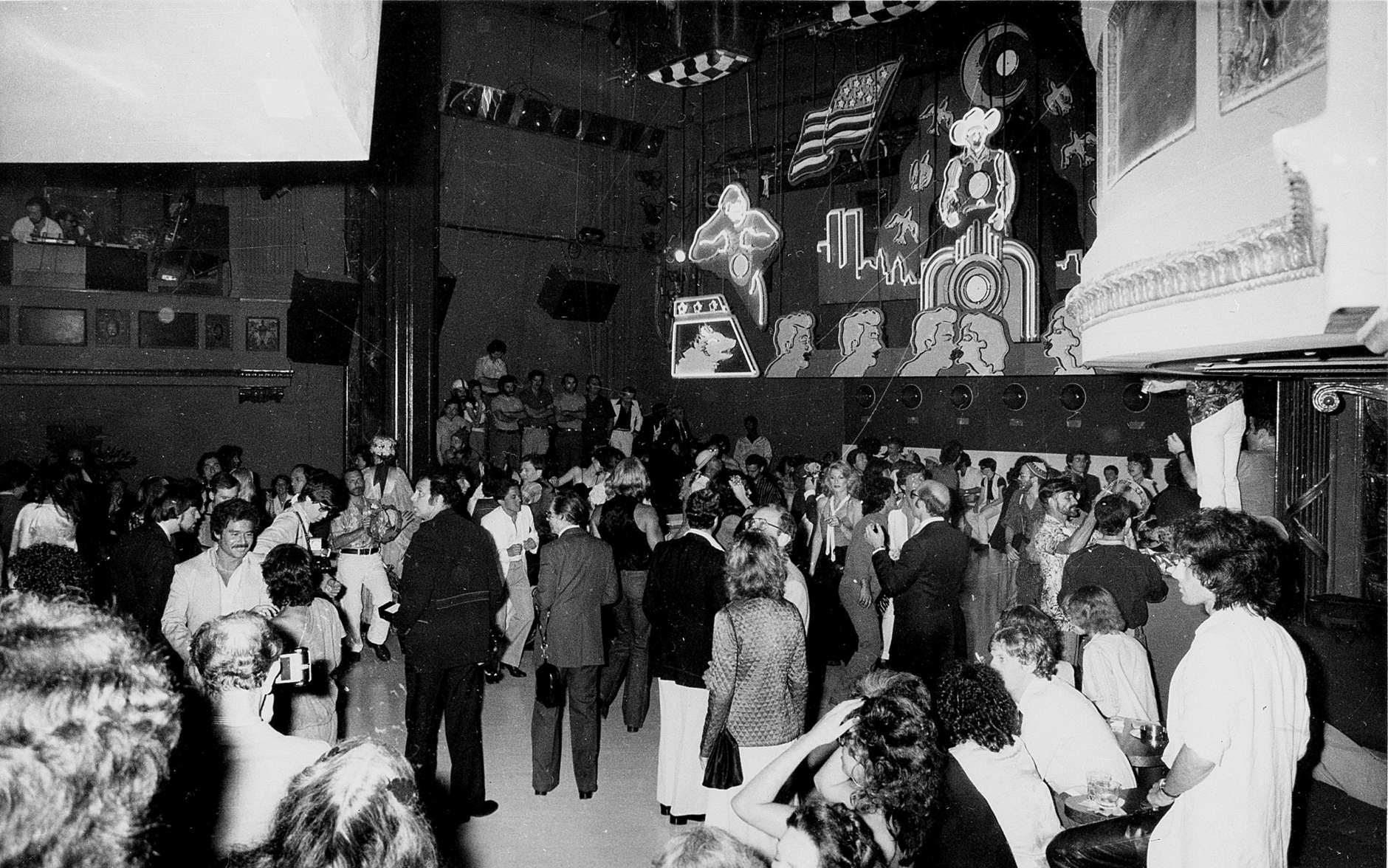

In the club

While the dream of disco was to bring all kinds of people together and foster togetherness and unity through dancing, it didn’t always work that way: Echols details in her book how the famously exclusive Studio 54 would turn away the insufficiently fabulous even when there was plenty of room inside, as well as discrimination against women and effeminate gay men at many gay discos.

“There’s sort of the grand hope of disco, that it will break everything down, but in practice, like any kind of subculture, it will develop its own rules and codes,” she said. “… One of the criticisms that was made of many discothèques was that they engaged in racial profiling.”

Echols saw it firsthand: She worked as a DJ in an Ann Arbor, Michigan, disco in the early 1980s that she said drew “a pretty broad demographic” in terms of ethnicity and education and income. She played some disco, but also plenty of funk, with plenty of Parliament-Funkadelic and The Gap Band, as well as hip-hop including Kurtis Blow’s “The Breaks.”

“Not everybody was thrilled with this,” Echols said. “I don’t know to what extent that happened at that club, but I do know that I was encouraged to play music that would appeal to the white gay men who tended to be the core audience there. I didn’t do that, and so eventually I was fired.”

“The mix of music I played, I thought, created a real polyglot dance floor. And I really loved that. But not everyone, apparently, did.”

Even so, Echols said of her disco experience, “it could be quite wondrous. Some of my fondest memories include DJing there.” She adds that punk-rock clubs had a similar ethos of inclusion that they didn’t always follow: “So I think subcultures do that.”

The real thing

Disco history has had a similar problem, as many critics and collectors make a stand for what they see as the “pure” disco “that didn’t know it was disco” (as one critic puts it in Echols’ book) as opposed to the more mainstream stuff that came later, particularly after the success of the movie “Saturday Night Fever” (which Echols calls an underrated movie that was lifted by The Bee Gees’ music — the cast and crew largely thought the movie was terrible until they heard the songs — and also had a lot to say about the changes in 1970s New York).

While acknowledging that “it’s true that there was some pretty bad stuff on the market” in the late 1970s, Echols remembers that at the time, nobody was making arguments about which disco song or track was the most authentic.

“Disco was not about authenticity; if anything, that was one of the reasons that rockers and hard-core soul-music aficionados hated it. Even disco … a rebuttal to realness, will end up generating something quite contrary to the original spirit of it. It’s funny.”

Now, 1970s disco is as likely to be heard at the grocery store as on the radio or the dance floor, but for Echols and others who were there at the beginning, it still has a hold.

Echols calls that the paradox “that lies at the heart of disco: Disco was never a kind of music that demanded very much from its audiences intellectually. Most of the lyrics were about getting down tonight, in one fashion or another. Yet … the music, as it played in discos across America, could have, and did have, a profound effect, particularly on its core audience.”

To attend the Library of Congress’ disco events, you need tickets; they’re free and available on the Library of Congress’ website.