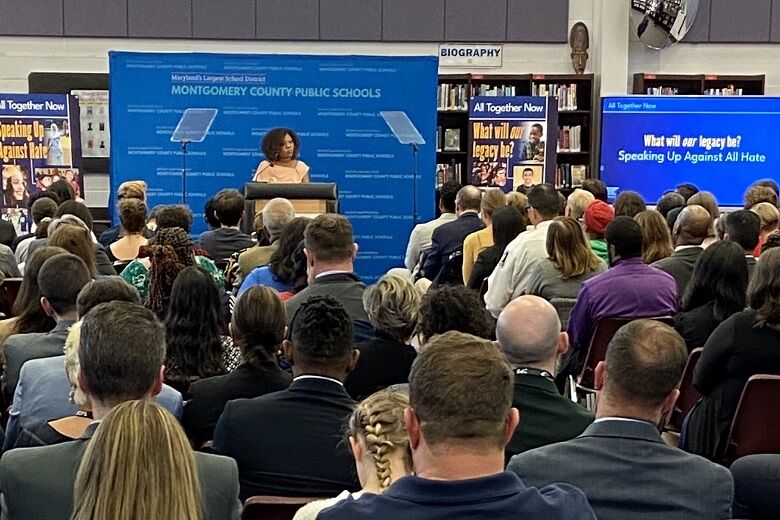

In a nearly hourlong speech in front of Montgomery County parents, students and community members Thursday night, Superintendent Monifa McKnight strongly condemned a significant increase in hate and bias incidents that have been reported across Maryland’s largest school system.

During the meeting at Rockville High School, McKnight detailed ongoing efforts to combat hate in schools, including actionable steps the school system is taking in response to the findings of its anti-racist audit.

Montgomery County schools is averaging about one hate incident per day in the current school year, she said, triple the number it reported compared to previous years and before the coronavirus pandemic.

“We have to stop just reacting,” McKnight said. “Stop addressing these incidents one at a time.”

McKnight unveiled a series of steps the school system plans to take to address the issues, including hate and bias training for all staff members in the coming months. The county will also create a group to monitor its progress on the anti-racist audit action plan.

Students will also learn about the role hate and bias has played throughout history, McKnight said. She laid out changes to fourth and fifth-grade curriculum to make sure they align with social justice standards. McKnight said the fact they were under review provided an opportunity to “teach students about the role that upstanders and bystanders have played throughout history.”

And, she said, through assemblies, student advisory boards and other means, the county aims to make time during the school day for students to learn about those issues.

McKnight’s comments marked the strongest formal, public rebuke of hateful acts in schools by a D.C.-area superintendent at a time when such incidents are on the rise. In many cases, families and communities are notified of incidents by school leaders.

“Fair and appropriate discipline plays an important role in how students will become better versions of themselves,” McKnight said. “Fair and appropriate means that parents are a presence in our schools in confronting issues together with their child in a conversation with school administrators. But it does not mean publicly shaming our students or conveniently convincing ourselves that we can suspend our way out of this.”

Antisemitic incidents have occurred “almost daily,” McKnight said, adding that students who practice Islam were concerned about their abilities to participate in school and extracurricular activities while they fasted during Ramadan.

McKnight drew on her experiences growing up in Orangeburg, South Carolina, where, at the time, she said there was a “white side of town, and a Black side of town.” She detailed the county’s rapid evolution, evidenced by things such as the Minority Scholars Program, Black student unions and leadership groups for the LGBTQ+ students.

But still, she said, some students have arrived at school to find things like Nazi symbols drawn on a desk.

“These unacceptable actions have no place in MCPS — they must be called out and not allowed,” she said.

“For too long, African American students have been confronted with the N-word while walking innocently to class,” McKnight said. “For too long, Asian American Pacific Islander students have dealt with simmering racism that boiled over during the pandemic. For too long, multiracial students have been told that by not fitting squarely into one category, or the other, they lack a place in our schools.”

Sami Saeed, an 11th grader at Richard Montgomery High School, said only some students are taking the hate incidents seriously. He applauded the actionable steps McKnight outlined Thursday.

“I’ve actually felt genuinely scared to come to school on some of these days,” Saeed said. “And I’ve talked to students that seriously do not feel comfortable in their own skin going to school today. And the fact that this was exacerbated, especially during and after COVID, it’s so disheartening and sad to see.”

Valarie Davis, with the Black Coalition for Excellence in Education, said McKnight’s plan lacked accountability and time frames for when the items would occur.

Byron Johns, education chair for the county’s NAACP chapter, praised the steps the school system is taking but added, “It can’t be just in schools, it’s going to have to be in the homes, in our communities. That’s where these kids are learning. That’s where we all learn first, is in the home. Hopefully our communities will be as eager to start looking at a different way to interact.”