As the world continues to grapple with the coronavirus pandemic, researchers at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Maryland, have taken a look at how similar epidemics have affected the D.C. area in the past.

Alan Hawk, the historical collections manager at the museum, said in a similar fashion compared to 2020, health officials in 1918 warned about the dangers of the quickly spreading H1N1 virus, commonly referred to as the Spanish Flu.

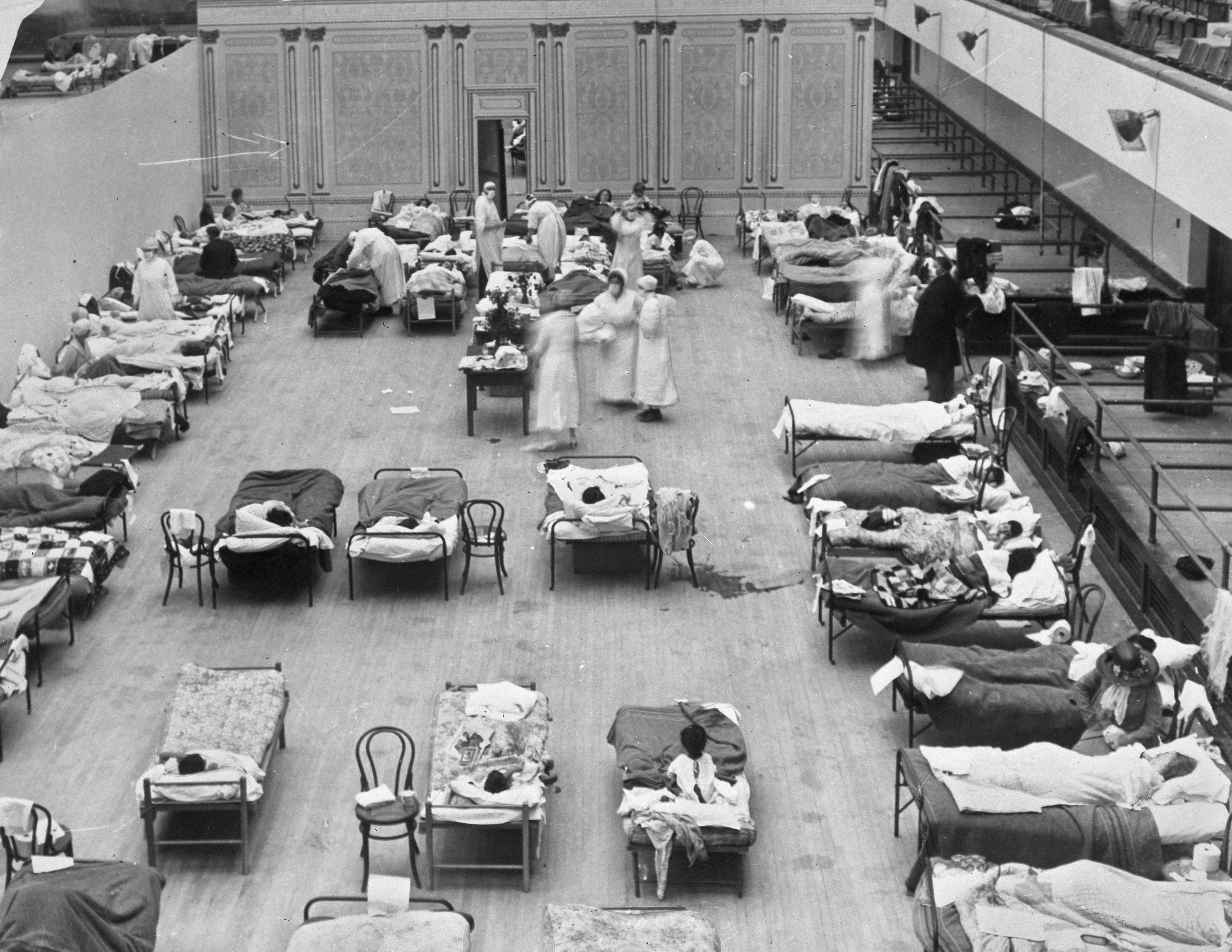

Social distancing measures were in place, albeit in a different form. Streetcar passengers were encouraged to keep their faces turned away so they would not breathe air from other people.

In a similar way compared to today, all cases of respiratory infections were monitored.

Patients who died were often those who had existing health conditions and other illnesses on top of the flu that made recovery harder.

One marked difference between the two is the most affected groups in the 1918 pandemic were otherwise healthy adults, between the ages of 20 and 40. Mortality was also higher in people younger than five and over 65.

Commuters were key spreaders, but unlike today, most of the initial spread of the 1918 flu happened through the military community.

Hawk said even though there were more white residents who contracted the flu in Montgomery County, proportionally, African Americans were hit the hardest.

This was due in large part to socio-economic issues, poor health and crowded living conditions.

Residents in Gaithersburg were affected the most in the region, with over half of the deaths that occurred in October of 1918 — at the height of the pandemic — coming from the African American community.

After seeing a decrease in cases and hospitalizations in the late fall and early winter of 1918, the largest county in Maryland had begun to see cases on a steady rise.

Hawk said newspapers documented the mixed reactions to venturing out in public in the late fall and early winter of 1918 and 1919.

“The meeting of the Janet Montgomery Chapter of the Daughters of the Revolution canceled their meeting for Dec. 12, while the ladies of the Methodist Episcopal church south of Poolesville, Maryland, announced their intent to hold their annual bazaar two days later.”

As the epidemic faded in 1919, residents began to resume their normal activities.

In all, 224 people died in Montgomery County from influenza or pneumonia over the fall and winter of 1918 and 1919 — a total of more than 6% of the county’s population at the time. It was lower than the rate of D.C. — which was over 7% — but higher than the national average of over 5%.

Historians say the 1918 pandemic caused between 50 to 100 million deaths worldwide.