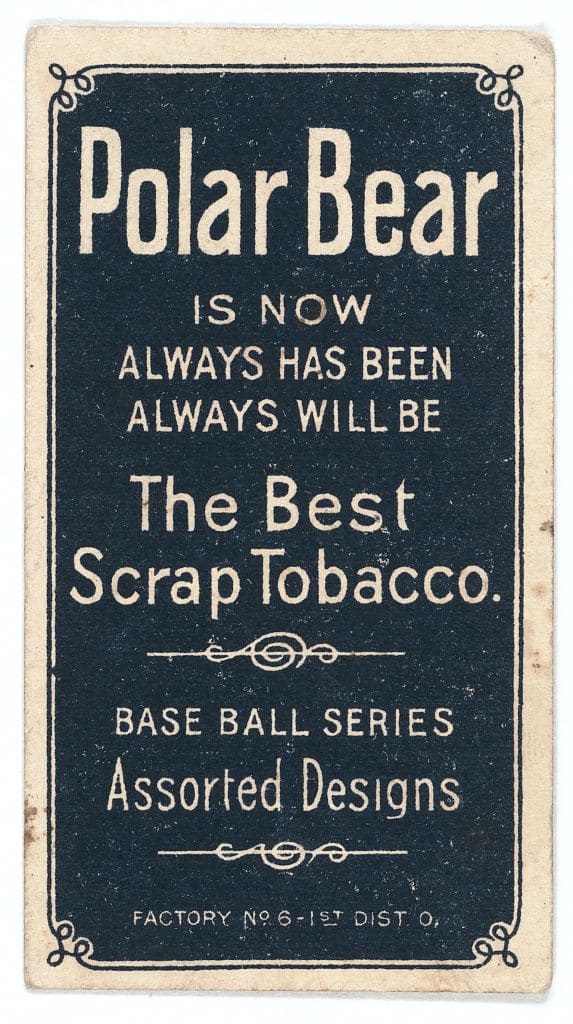

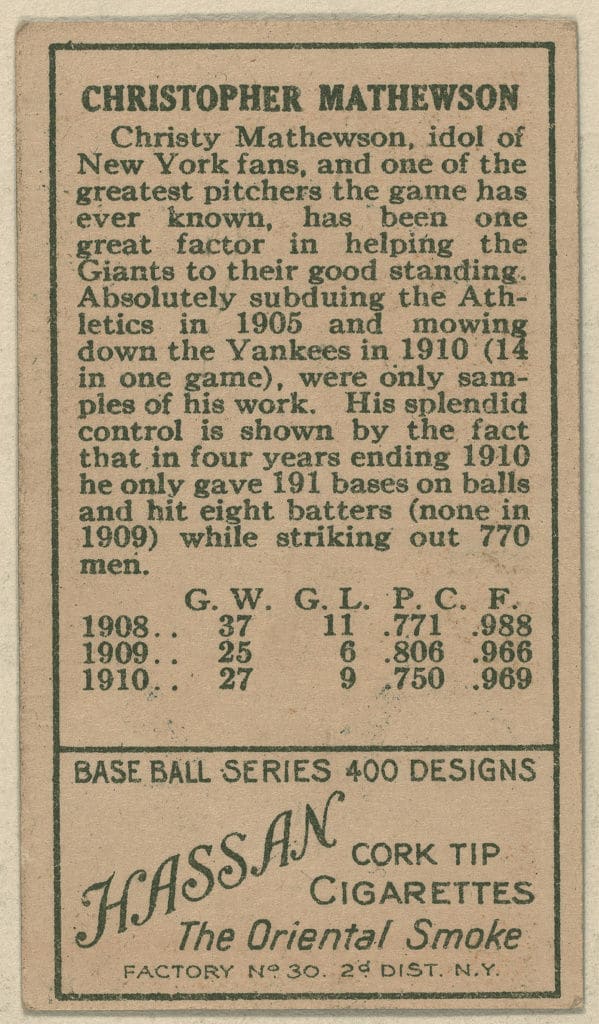

WASHINGTON — As much as the rectangular, cardboard prints themselves, people growing up in the ‘80s and ‘90s remember the dry, chalky slab of gum that accompanied baseball cards in their plastic packs. But when the medium was first invented, the cards themselves were the added bonus. The product? Cigarettes.

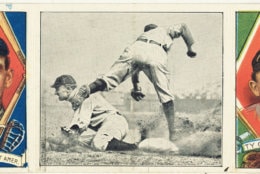

That’s just one of the many revelations of “Game Faces: Early baseball cards from The Library of Congress” (Smithsonian Books), a history of the first generations of cards, from 1887-1914, by Peter Devereaux.

The cards themselves had little value to the general public at first, but quickly became collector’s items.

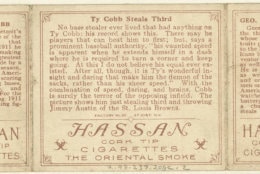

“Somebody would buy a pack of cigarettes and rip it open and just drop (the card) on the floor of the tavern,” Devereaux told WTOP. “I just found it astonishing at the time that children would wait outside of taverns in the morning, and the proprietors would allow them to go around and collect up all the cards that were left on the floor from the night before.”

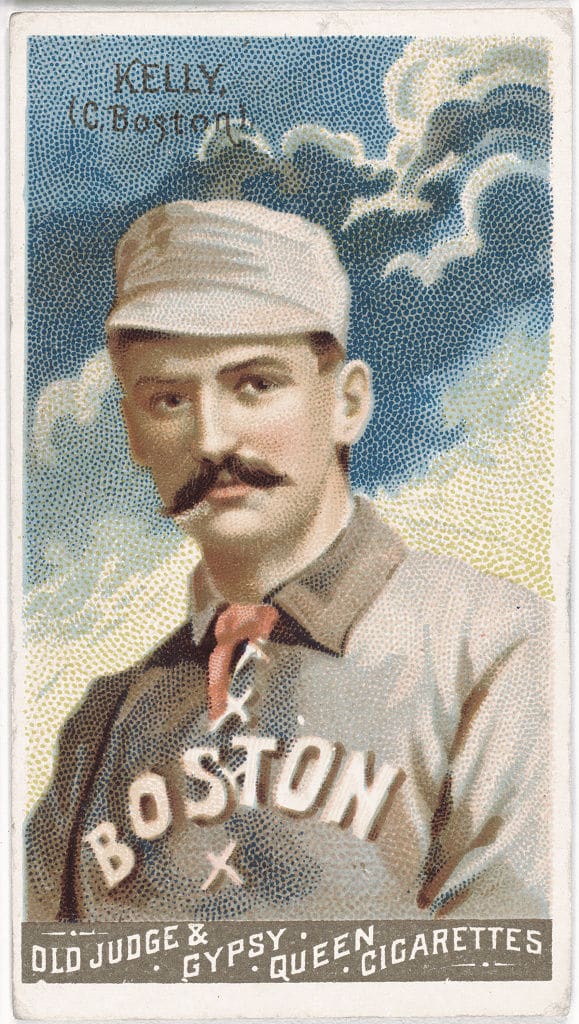

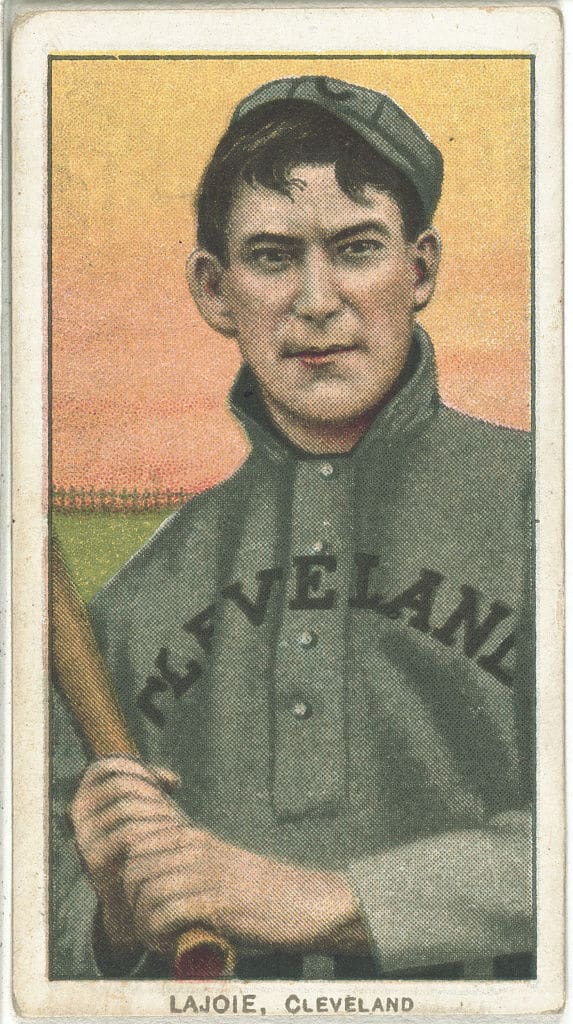

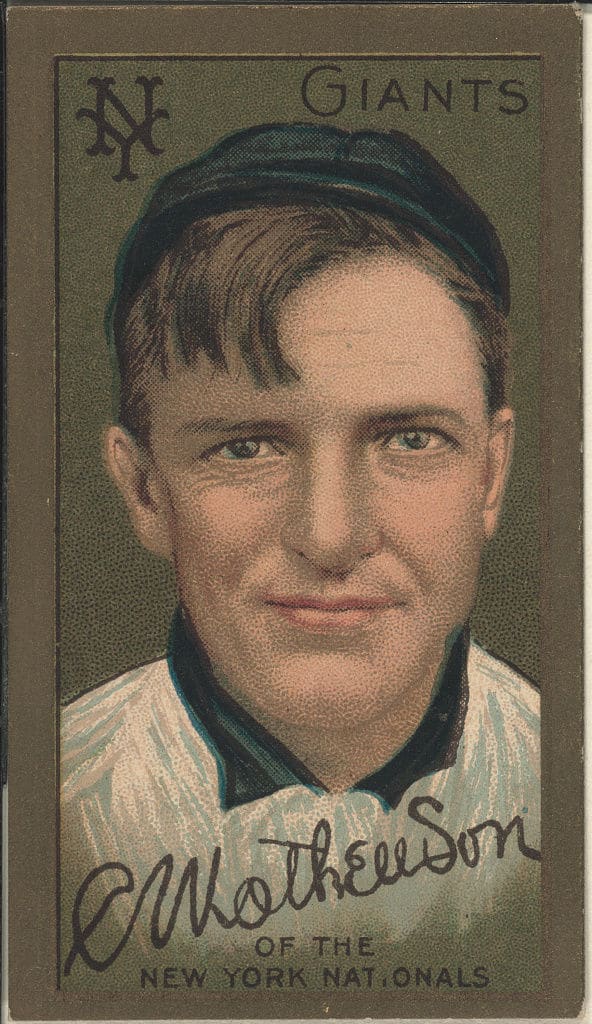

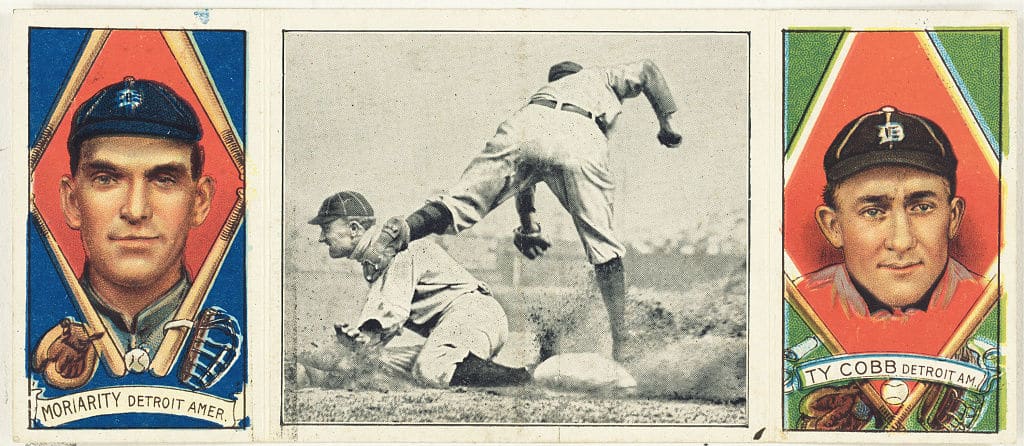

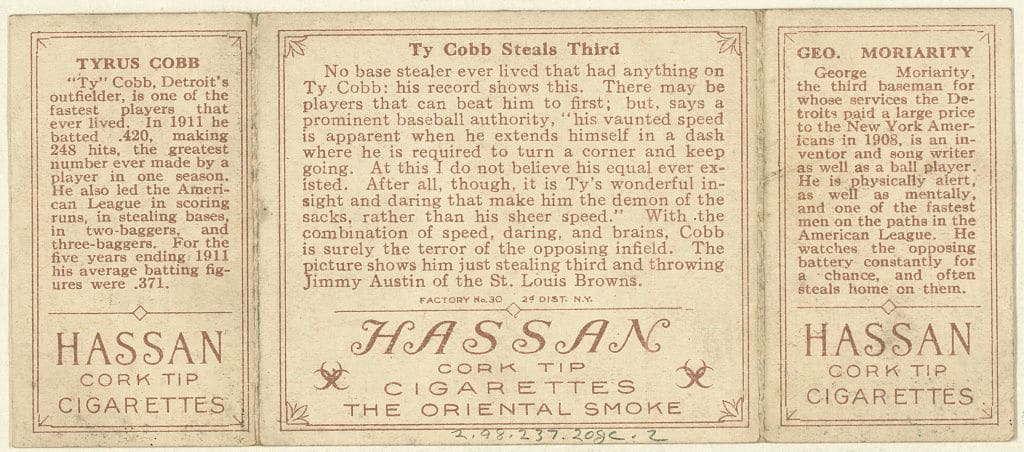

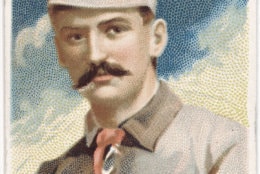

The appeal, especially for kids of the era, is easy to understand. There was no television, no sports magazines, no internet to bring so much as a basic image of what players looked like to the masses that had never seen them play. Even newspapers of the time only ran the occasional drawing, rather than photographs.

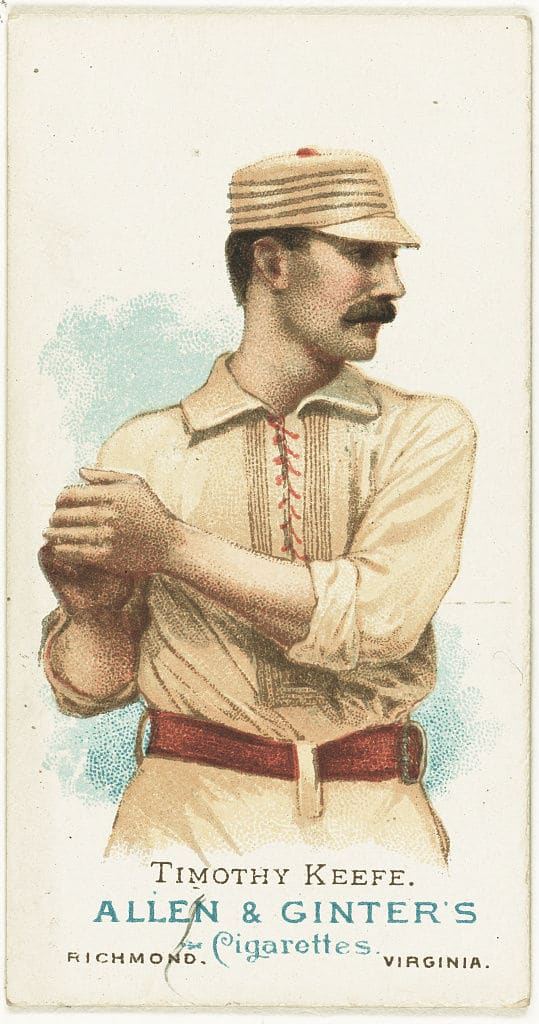

“In the 1880s, a lot of fans didn’t know what their favorite players even looked like,” said Devereaux. “So this was the first time a visual representation of the stars of the game — King Kelly, Cap Anson, and others … I think it was just the novelty of seeing the representation of a baseball player’s face, and also this was the time when the game was really gaining a foothold as our national pastime.”

Devereaux chose to focus on this particular era of baseball cards not simply because the LOC’s Benjamin Edwards Collection ended at that point, but because of the fundamental, societal shifts that changed the nature of the industry after 1914.

“Because of the outbreak of World War I, there was a paper rationing,” said Devereaux. And after the war, there was a large temperance movement and sort of a progressive era, and the idea of marketing baseball cards and cigarettes to children just wasn’t a sort of good idea anymore for cigarette companies.”

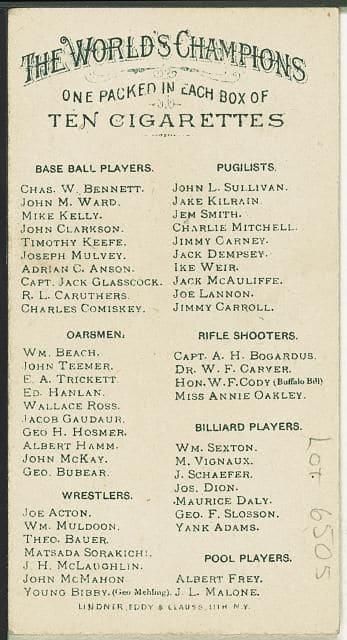

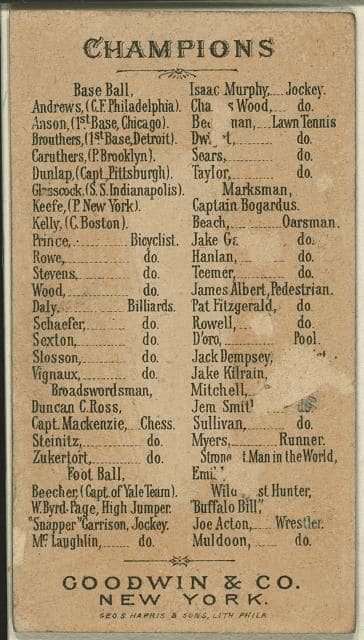

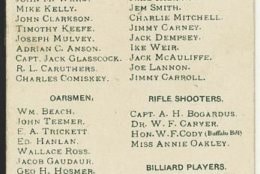

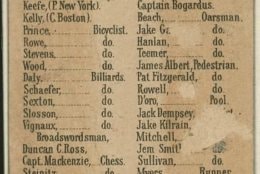

Baseball players weren’t the only subjects of early card makers, even though they prevailed as the most popular over time.

“It was boxers, and rowers, and horse players, and Civil War generals, and actresses,” said Devereaux.

But what of baseball cards’ future? In a world flooded with images, has the photograph itself become devalued? Is there value in something as analog as a card anymore?

“I have an 8-year-old son today and he collects cards today, which I find kind of neat,” said Devereaux. “So I think there’s something enduring about the cards … Having that tangibility in your hand, the same reason I think print books and vinyl records and those sort of things still have a foothold in our cultural economy.”

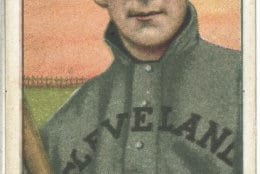

So as the photographic image becomes ubiquitous, inescapable, and digitized across all the screens that dominate our daily lives, the card companies are returning to their roots, to the creative origins of the cards. Devereaux spoke with Topps when compiling the book and found they are reissuing a set of Allen & Gintner cards, with watercolor backgrounds and other touches beyond simple photographs. If baseball cards are to make a comeback in the future, perhaps it will be from the sets that look more like the ones deep in the past.

“They’re really interesting cards. They have a little more artistic flair to them, a little bit more dynamic color,” said Devereaux of the throwback set. “I think it kind of comes full circle, in some way.”

Devereaux will be hosting a reading at Greedy Reads in Baltimore’s Fells Point neighborhood on Friday, Jan. 11 at 7:30 p.m.