All this week, WTOP’s team coverage of “The Key Bridge, One Year Later” revisits an unthinkable, tragic collapse that sent shock waves around the nation and forever changed the face of Baltimore.

This video is no longer available.

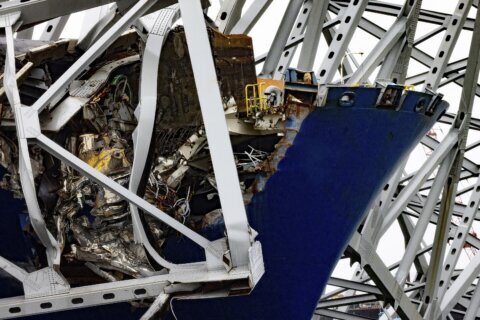

It’s been a year since the crash that collapsed the Francis Scott Key Bridge into the waters of the Patapsco River in Baltimore.

An expedited cleanup mission got the wreckage out of the water and opened up the channels that allowed cruise and cargo ships to return to Baltimore within a couple of months.

That brought jobs back to places like Dundalk and Seagirt, Maryland. At the ports, it’s been full steam ahead again for a while now.

But for those who live there, the impact is still being felt on a daily basis. Adaptations have been made, which has impacted how they commute, socialize, shop and even see a doctor. Even going out to run a simple errand down the street brings with it a telltale sign that the bridge is still missing.

Data provided from the Maryland Department of Transportation Authority to WTOP shows that travel times along Interstate 95’s Fort McHenry Tunnel and the Interstate 895/Baltimore Harbor Tunnel have generally increased during peak travel periods when comparing fall 2024 data to prior years.

Average daily traffic volumes increased by 15% at the I-95 Fort McHenry Tunnel and 7% at the I-895/Baltimore Harbor Tunnel, when comparing fall 2024 data to the average of the same period in fall 2022 and fall 2023, according to data from MDTA.

The most significant increases, according to MDTA data, were observed southbound in the morning peak times and along the northbound direction in the evenings. There was an increase of about 20 minutes during peak evening commute time on Fort McHenry Tunnel between I-695 south of Baltimore and I-895 Tuesdays through Thursdays; and about 15 minutes on those days in the peak morning commute.

The I-895/Baltimore Harbor Tunnel between I-95 south of Baltimore and I-95 north of Baltimore Tuesdays through Thursdays northbound peak evening travel times increased by about 25 minutes; and southbound peak travel times in the mornings increased by about 15 minutes.

Make no mistake, traffic and commuting in and out of an area that’s bordered by water on three sides is an ongoing complaint now. It’s one way in and out now — for everyone.

“I don’t think any of us realized the impact it would have on us,” Brenda Ryan said.

“We have to readjust everything. You want to make your doctor’s appointments earlier so that you’re in between the busy time of traffic. Even shopping, the city is more expensive to shop, so if you don’t want to spend the time driving to Anne Arundel County … the quickest route would be going to the city,” she said.

Her husband, Richard, who manages a Veterans of Foreign Wars Hall off North Point Boulevard in the Edgemere area, said the daily trips into Anne Arundel County are far less frequent now that the bridge is gone, since each trip to and from places like Costco in Glen Burnie and other area stores take at least twice as long as it used to.

Those stores sit just off I-695 and the bridge.

Now, it involves more planning and one much longer trip once a week.

“The ease of commute convenience is no longer there,” he admitted. “Having to go 20 miles outside your normal route just makes it difficult so you don’t shop there.”

“You’re spending more on gas,” Brenda said. “Any way you look at it, you’re spending more.”

“That extra time you’re sitting in the car. … Time away from the family, that’s probably a bigger cost than” the wasted gas, her husband said.

The collapse’s trickle effect

There’s also been a cost to the VFW Hall, which has seen weekly cornhole tournaments and other rentals decline, because people from Anne Arundel County were not willing to make a longer trip anymore.

“Instead of driving 20 minutes to the venue, now they’re driving an hour, if not longer,” Brenda said.

The disruption is also being felt by parents of kids in youth and high school sports, who tend to have longer travel times to tournaments and ball fields.

“The kids are spending more time in the vehicle,” she noted. “Some of the games would have been over the bridge, 20 minutes — not a problem. Now, they’re spending 45 minutes to an hour in the vehicle.”

For Brenda, some trips through the tunnels are unavoidable. That includes a periodic trip to see a specialist for a medical procedure at University of Maryland Baltimore Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie.

“It is a 2 to 3-hour appointment,” she said. The side effects leave her worn down as she makes the long trip back. “It doesn’t help my condition. It doesn’t help.”

She also said, anecdotally, it feels like they’re seeing more traffic crashes in their community.

Lives turned upside down

Sitting inside the VFW Hall managed by Richard, Jim Hollingshead expressed relief that he was retired since he used to commute back and forth over the bridge every day. His wife did the same.

“The Key Bridge is very seldom backed up,” he said. “Whereas the tunnels, every rush hour you know they back up — going and coming.”

“For the past year, my life has been turned upside down due to the bridge not being there,” said Larry Randolph, who has been driving trucks around the region for nearly 30 years.

Most days, he starts out of a yard on North Point Boulevard, drives through the tunnels and takes a load of cargo to places like Sterling, Virginia, and Landover, Maryland. If he’s not on the road by 4:45 a.m., those trips take at least 30 minutes longer each way.

It also means more wear and tear on his truck and covering big increases in fuel costs thanks to those extra miles driven — all expenses he has to pay for.

“This past year, I spent a ton of cash on stuff that normally will last me two, three years,” Randolph said. “I just put new tires on my truck just before the bridge went down. They’re almost done now.”

He said he’s spent about six months driving cargo from Norfolk to Baltimore every day. The tires alone cost nearly $3,000. Add in new brakes and other maintenance, and Randolph is looking at about $5,000 to keep his truck on the road.

He’s spending twice as much on fuel as he used to, and when he can go through the tunnels, that’s another $24 each way. Sometimes, he’ll drive through the city instead.

In all, it’s estimated by researchers that the lack of a bridge adds more than a million hours of travel time and nearly $93 million to the trucking industry’s operating costs.

Fast money, no more

The biggest reason Randolph, in particular, made about $30,000 less over the last year is because of the cargo he can’t drive through the tunnels — whether they’re backed up or free flowing.

Randolph used to drive lots of what’s considered hazardous material, which is from the docks in Dundalk and Seagirt and often taken to places like Brooklyn Park and Curtis Bay in northern Anne Arundel County.

“Normally, it would take 14 minutes to get from the Port of Baltimore to Curtis Bay,” he said.

Randolph estimates he made an extra $3,500 a month making the haul over the Key Bridge near the end of his day.

It was the definition of fast money.

Now, if traffic is cooperative, it takes nearly an hour to drive almost all the way around the Baltimore Beltway. Oftentimes, especially with all the road construction happening right now, it’s well over an hour.

With the tunnels off limits, he just doesn’t bother. The cost of getting caught driving through one with hazmat materials is far from cheap.

“I’m not rolling the dice like that, because I still love what I do, and I got a lot of trucking left in me,” Randolph said. “So I just picked my loads according to how I feel comfortable with running. I would rather just take a hit than putting all that pressure on my truck and just sitting in traffic. You really don’t make no money that way just sitting in traffic.”

Looking to the future

It’ll still be a few years before a new bridge is built, but eventually, the trucks that chug up and down North Point Boulevard will have more than one way on and off Sparrows Point and the port of Baltimore.

Eventually, traffic patterns will return to normal. But while the port itself is at full capacity receiving cargo that sails up the Chesapeake Bay, things are far from normal in this part of Baltimore County.

A bridge that fell down a year ago is still causing problems every day.

“I’m eager to see a new bridge. If it could be built yesterday,” Randolph said. “If they need some help, man, I go down there and roll my sleeves up and help them get it going. Because that bridge was everything to what I do.”

Get breaking news and daily headlines delivered to your email inbox by signing up here.

© 2025 WTOP. All Rights Reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.