This article was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

This content was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

The mere mention of “artificial intelligence” inspires a lot of dread and wonder in the general populace.

Yet it’s an overbroad subject. AI can mean anything from self-driving cars to facial recognition technology. Robots that perform unenviable tasks to new mashups of popular songs. Enhanced fraud detection at banks to deep video fakes meant to dupe the public.

“I can’t think of any endeavor where AI in some ways can’t be helpful,” said Anupam Joshi, chair of the Computer Science and Electrical Engineering Department at the University of Maryland Baltimore County. “And as you think about AI, there’s a lot of hype around this.”

But a number of academics, scientists, intellectuals and environmentalists in Maryland are starting to buy the hype in at least one critical way: AI, they believe, may be able to help protect the world’s land, air and water and could help to mitigate climate change.

“In the last couple of years there’s been a lot of excitement about AI, a lot of fear about AI,” said Joel Dunn, president and CEO of the Chesapeake Conservancy, an Annapolis-based regional conservation nonprofit. “There’s really no doubt that it’s touching every part of our lives…It comes with some controversy as we come to understand how AI will change society as we know it. But what some people may not know is that AI may have the potential to save the planet, including right here in the Chesapeake Bay region.”

The concept is hardly new: After all, WALL-E, a popular animated movie from 2008, featured a robot who traveled a desecrated Earth, cleaning up humans’ environmental messes.

Today, at its most basic level, AI is helping climate scientists and meteorologists with the rudiments of their profession.

“Our ability to predict the weather has vastly improved over the last decade, and a big reason is machine learning,” said Tim Finin, another computer science and electrical engineering professor at UMBC, who, like Joshi, was testifying at a state legislative hearing on AI earlier this summer.

When policy experts talk about using AI to help the environment, they aren’t talking about the latest — and hottest and most controversial — iteration, known as ChatGPT. That’s an AI-powered language model, capable of generating human-like text based on context, past conversations and prior writing samples.

“This AI stuff is not as new as everyone is making it out to be,” said Andrew J. Elmore, a professor of landscape ecology at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, who just completed a project mapping forestland in Pennsylvania, using artificial intelligence.

In a recent conversation with reporters at the state’s Wye Island Natural Resources Management Area, where he announced a new state plan for monitoring the Chesapeake Bay’s health, Gov. Wes Moore (D) said AI may become part of Maryland’s climate solutions strategy.

“Being able to understand the role that AI is going to be able to play…is important, and it’s something our administration is going to move very deliberately on,” he said.

The Chesapeake Conservancy is regularly putting the application to the test. It is perhaps the leading institution in Maryland that’s using AI for climate research and advocacy — though it is by no means the only one. The organization has recently completed two projects that conservancy leaders believe can be extrapolated in unlimited ways. One relied on models the conservancy’s researchers developed to map waterways in discreet areas. The other tracked large solar energy installations and offered predictions for where future solar arrays may be sited.

Last year, using deep computing, conservancy researchers helped the Harry R. Hughes Center for Agro-Ecology on the Eastern Shore compile a comprehensive look at Maryland’s disappearing forestlands and tree canopy. The study resulted this year in the first meaningful forest protection legislation in the General Assembly in decades.

“There’s this acknowledgement that we need to leverage new approaches in technology and financing and application to advance the movement,” Dunn said. “And AI and machine learning are one component of that, and a major component of that.”

Mapping of waterways, of course, is not a new exercise. The National Wetlands Inventory, overseen by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, has existed for decades. The agency produces and distributes maps and other geospatial data on wetland and deepwater habitats and monitors changes in those habitats over time, using photographs, satellite technology and other data.

But at a time when federal and state officials, farmers, ranchers, scientists, corporate leaders and environmentalists cannot even agree on what actually constitutes a body of water — and have been slugging out their differences in legislative debates and through litigation — Chesapeake Conservancy has sought a more aggressive and comprehensive survey. A decade ago, the conservancy created the Conservation Innovation Center, and began raising money to hire scientists to run it.

“That was a conscious effort to leverage emerging technologies, particularly geographic imaging systems and cloud-based computing to help us develop better data to make better decisions,” Dunn said.

When it came to mapping wetlands, conservancy scientists trained a machine-learning neural network model for high-resolution wetland mapping with publicly available data from Mille Lacs County, Minn., a region north of the Twin Cities with abundant lakes and rivers; Kent County, Del., which lies along the Delaware Bay; and St. Lawrence County, N.Y., which is partly in the Adirondack Park and features the St. Lawrence River and several other significant waterways. Using three different technologies (AI, remote sensing data from satellites, and cloud computing), researchers were able to map the waterways in the three counties — including assessing where water bodies had been before they disappeared or were covered up by construction projects — at a very high accuracy rate of 94%.

“It’s pretty unusual for an organization of our size to have that level of integration,” said Mike Evans, Chesapeake Conservancy’s senior data scientist. “It puts us at the forefront of what conservation organizations are doing.”

The study results were published in the Science of the Total Environment, an academic journal, which gave the Chesapeake Conservancy researchers a great deal of satisfaction and peer-reviewed validation. And the scientists believe what they found in the three counties can be extrapolated to the entire Chesapeake Bay region. They have shared the results with the leaders of the Chesapeake Bay Program, the regional partnership of federal, state and local officials that has been working on Bay clean-up for the past four decades.

“It’s a great example of how you can leverage better data to make better policy,” Dunn said. “The wetlands are like the kidneys of the Chesapeake Bay. They’re crucial to maintaining and restoring critical parts of the bay. So we’re really excited to add this tool and data to the decision framework for the community moving forward.”

‘The technology exists to map this data in ways we couldn’t do before’

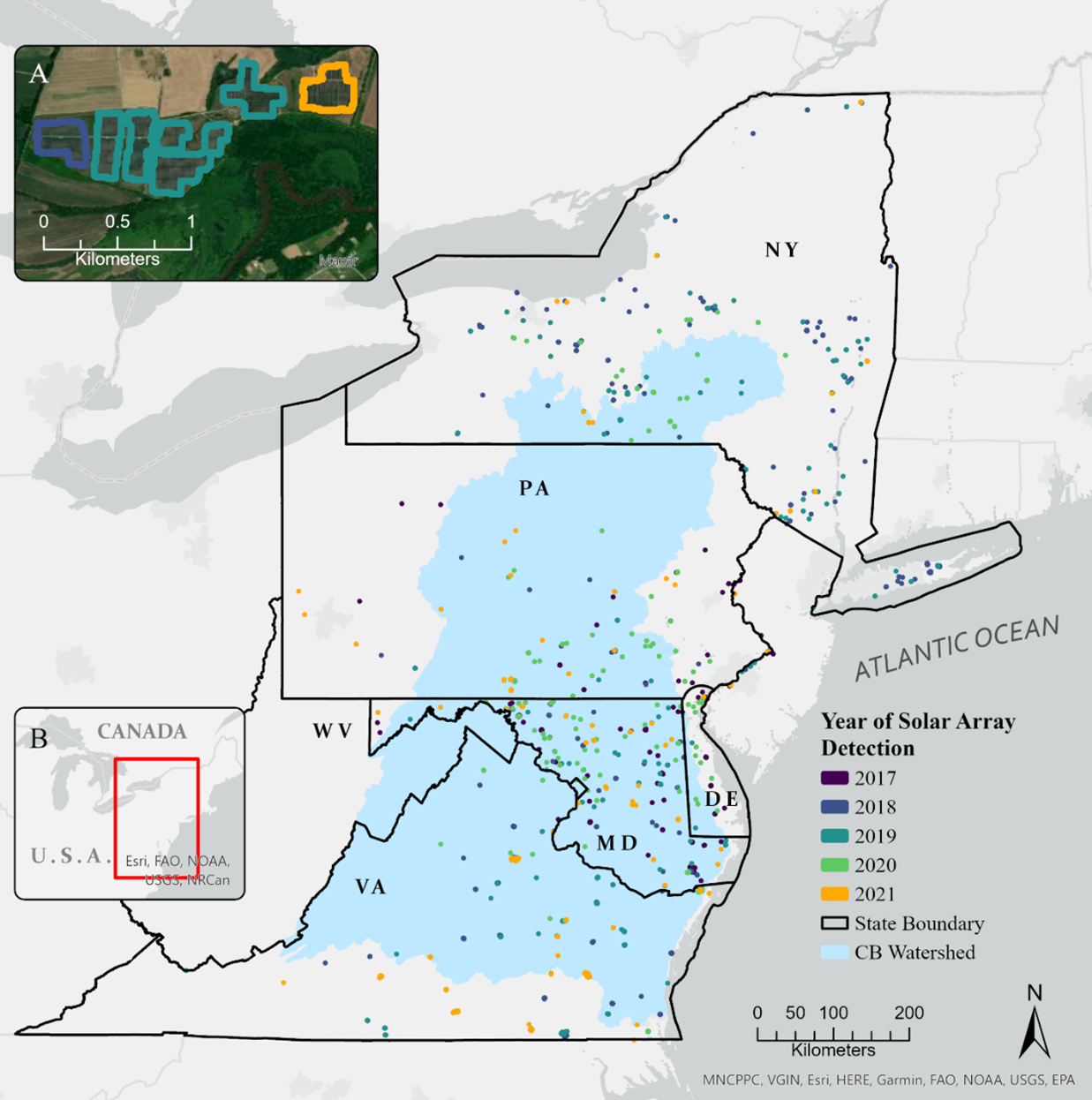

The Chesapeake Conservancy solar array study sought to map where big solar installations have been placed throughout the six Bay watershed states — Maryland, Virginia, Delaware, West Virginia, Pennsylvania and New York. Using the AI technology was essential, conservancy leaders said, because it’s hard to distinguish solar arrays from bodies of water and runoff on impervious surfaces on standard satellite images. So the AI mapping enabled researchers to not only see where the solar installations are, but also to project where they are likely to wind up in the future. The results were published in Biological Conservation, a scientific journal.

“It was a challenge that lent itself to the strengths of AI so it made a lot of sense,” Evans said. “There’s this need for the data. The technology exists to map this data in ways we couldn’t do before. So that is really a nice example of the sweet spot where AI can really make a difference in the conservation space.”

Evans presented the conclusions at a clean water conference in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, earlier this year. He said some conservation leaders were dismayed seeing the projections that a number of large solar projects are inevitably going to wind up on land that environmental groups are trying to protect.

“You could hear some grumbles in the audience,” Evans recalled, “because people didn’t like seeing their area lit up as a high probability solar place, and my comment is, ‘If you don’t like how this map looks, good. Now is the time to do something about it.’ This is what we think will happen if the status quo continues.”

Moving ahead, the conservancy is in the early stages of a project that’s using AI to map the biodiversity of the Chesapeake Bay region. Kumar Mainali, a data scientist who is heading the research, said the group aims to track the distribution of hundreds of species — and pinpoint suitable habitats for each species throughout the region, “so that we can manage and conserve them efficiently.”

“To do anything, first we need the data about the species,” Mainali said.

The AI will enable researchers to home in and observe smaller species, using a resolution that’s 1,000 times finer than conventional mapping.

“It’s a multi-year project,” Mainali said. “I have completed modeling about 10 species so far.”

Mapping Pennsylvania forests and the undersea world

Chesapeake Conservancy researchers aren’t the only people in Maryland using AI to make environmental inquiries.

Elmore, the professor at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science Appalachian Laboratory in Frostburg, just finished his project mapping forestland in Pennsylvania, but it has yet to be published. UMCES was hired for the job by the Natural Resources Conservation Service, a division of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which is interested in managing forests to maximize bird habitat.

Elmore said the state of Pennsylvania does a good job of keeping track of where forests are harvested on public land, but struggles to monitor what is taking place on private lands. UMCES researchers used photos and data taken from airplane radar and combined it with what was known about logging activity on public lands to hypothesize what’s been happening around the state.

“It really helped that the state kept such great training data” on public lands, Elmore said. The researchers’ basic conclusions: “People on private lands in some cases follow best practices, but in other cases, they don’t. On some private lands they’ll just come along and harvest the most valuable trees.”

Eventually, UMCES wants to model the bird habitat itself in the Pennsylvania forests.

“We want to know where the birds are, but what we really want to know is where the created habitat is,” Elmore said. “The goal eventually is to give people tools to know what is the best treatment you can get for bird habitat.”

UMCES will turn over its data to the Natural Resources Conservation Service, but will also offer the federal government options for how to best preserve, protect and extend bird habitat in Pennsylvania, based on what the researchers found.

“The opportunities are pretty wide open if we can identify those situations that are really valuable and unique for mapping conservation,” Elmore said.

Meanwhile, a Johns Hopkins University professor has recently brought his longtime expertise using AI to study the ocean floor to classrooms and research institutes in Baltimore.

James Bellingham is a pioneer in the field of autonomous marine robotics who has led research expeditions from the Arctic to the Antarctic and is now executive director of Hopkins’ Institute for Assured Autonomy. Bellingham has spent decades developing and employing autonomous underwater vehicles for research, through high-level positions at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution on Cape Cod and at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute in California, among other institutions.

Bellingham said research of marine life and weather conditions has always been years behind the ability to probe what takes place on dry land or in the sky, calling the conditions miles beneath the ocean’s surface “an observational challenge.” Much of what takes place in the ocean is opaque to most satellite systems and opaque to radio frequency, he said.

Bellingham and his colleagues have developed autonomous vehicles that can spend up to six hours at a time on the ocean floor, collecting data. But what they’ve discovered over the years is that transmitting information from the sea floor to the surface is a major challenge. Initially, they would bring the vehicle up to the surface and spend six hours downloading the information it had collected. But they came to realize that given the volatile conditions at the bottom of the ocean, by the time they were able to observe the data they were no longer doing so in real time.

“We did a terrible job, though it was better than anything else you could do,” Bellingham said. “In the ocean, it takes a long time to get stuff to work.”

What Bellingham and his collaborators have developed more recently is an autonomous vehicle with communications systems capable of transmitting data to researchers at the surface in real time, likening the process to sending and receiving text messages. What they’re attempting to measure is how conditions at the bottom of the sea are affecting the biology and chemistry of the ocean, the life that currently exists there — and vice-versa. It’s a less obvious and visible aspect of climate change.

“They’re beginning to tease apart how these organisms are being shaped by the environment they’re in and how they’re shaping the environment,” Bellingham said. “Some people think we’re moving to an ocean that doesn’t exist today. There’s a zillion hypotheses for what might happen.”

A legislative response?

At a recent conference of state environmental regulators in Washington, D.C., AI was a frequent topic of discussion. Amanda Lefevre, the deputy commissioner at the Kentucky Department for the Environment, said environmental work “is a really good application” for AI.

“You can run lots of scenarios, thousands of different scenarios, in thousands of different ways,” she said. But she also joked about the technology’s prevalence. “I may not have a job in two months.”

Colby Manwaring, vice president of Innovyze, a tech company in Portland, Ore., that develops software for water infrastructure companies, told the state officials that in his view, AI can only go so far in deconstructing environmental conditions and challenges.

“We don’t always need AI,” he said. “We always have a lot of analytics tools and planning and operational tools. AI can help optimize some of that.”

Manwaring said that AI can’t, for example, tell someone how much it’s going to rain on any given day because forecasts can only be so precise.

“Incomplete data is a fact of everyone’s life,” he said. “It’s never as complete as you want.”

And AI continues to raise fears in society and is drawing more scrutiny from lawmakers across the country, inspiring 80 separate bills in state legislatures across the country this year, Quinn Laking, a University of Maryland School of Law student who has been researching AI for the University of Maryland Center for Health and Homeland Security, testified at a legislative hearing recently.

“It’s definitely the new hot topic,” she said.

Maryland is no exception. The legislature’s Joint Committee on Cybersecurity, Information Technology, and Biotechnology, held the first of two public hearings on AI in late June. It was a general survey about the applications of AI, with an array of experts and scholars speaking. The committee’s co-chairs, Sen. Katie Fry Hester (D-Howard) and Del. Anne Kaiser (D-Montgomery), said the panel would discuss potential legislation for overseeing AI in the state at a hearing in October.

“It’s past time for there being some kind of legislative framework,” Kaiser said.