Maryland’s getting more than $650,000 from the federal government in a plan to prevent disease in wildlife. The effort could also benefit the state’s critical poultry industry, its consumers and public health.

This week, members of Maryland’s Congressional delegation — U.S. Sens. Chris Van Hollen and Ben Cardin, along with House members Steny Hoyer, Dutch Ruppersberger, John Sarbanes, Kweisi Mfume, Jamie Raskin, David Trone and Glenn Ivey, announced that the funding would go to the Maryland Department of Natural Resources to prevent the spread of wildlife diseases, including avian flu.

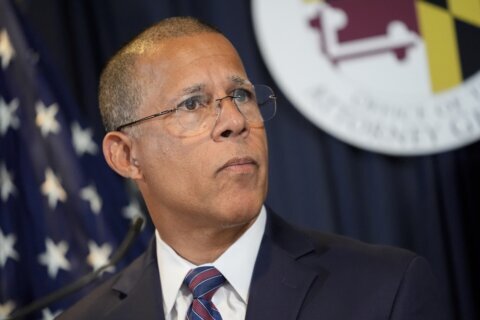

“The work is important,” said Dr. Nathaniel Tablante, a professor of veterinary medicine at the University of Maryland, College Park. Avian flu can “jump” from birds to mammals, he added.

“There is a potential for these types of viruses to infect humans, that’s why we’re being very careful,” said Tablante.

According to the latest report on avian flu nationwide, in May, 837 flocks were affected by the latest outbreak, with 511 being backyard poultry operations. The rest were commercial outlets. Tablante said that meant a total of more than 58 million birds were affected nationally.

The avian flu outbreak that began in 2021 resulted in massive culling of flocks that caused a spike in prices for poultry and eggs. “It has subsided a little bit. That’s why you’re seeing a kind of a stabilization in the prices of eggs,” said Tablante.

Wild birds, specifically waterfowl (think ducks and geese), are “reservoirs” for avian flu said Tablante, and it can be transmitted through their feces.

And that, he said, “creates a problem for backyard flocks, because they’re mostly out in the open air, free range” where they can come into contact with feces infected avian flu. “As opposed to commercial poultry that are enclosed and protected” by being indoors.

“Maryland has been lucky,” said Tablante. “I mean, we have not seen outbreaks in our broiler chickens on the Delmarva Peninsula,” he said, while two egg-laying producers were affected.

In past outbreaks, the spread from wild bird populations to domestic poultry came through “lateral” transmission: a hunter or farmer walking through a field might step on waterfowl feces, then head to their farm without changing their shoes, said Tablante.

That’s why a large part of Tablante’s job is educating poultry producers on “biosecurity measures,” including things like washing down farm equipment — including their vehicles, and wearing personal protective equipment.

With the addition of federal funds just announced, Maryland’s Department of Natural Resources will form a working group to tackle wildlife disease management and partner with the University of Maryland to prevent and develop responses to future outbreaks.