This article was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

This content was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

After Wes Moore made history Tuesday to become Maryland’s first Black governor, the 44-year-old author and former nonprofit executive joined a short list of former Black governors in America, even as he prepares to govern an increasingly diverse state.

After the 2020 Census, Maryland is no longer a majority-white state, with 51% of state residents identifying as non-white.

Todd Eberly, a political science professor at St. Mary’s College in St. Mary’s County, said the state’s General Assembly is currently more than 61% white.

Women in the legislature account for 39%, Eberly said, but the female population exceeds 50%.

“Maryland’s General Assembly, even though it is considerably more diverse than most state legislatures, it still doesn’t reflect the diversity of the state,” he said.

But after Tuesday’s election, the state tallied several firsts when it comes to racial and gender representation in state government: former Del. Aruna Miller was elected with Moore as the state’s first lieutenant governor as a woman of color; U.S. Rep. Anthony Brown will become the state’s first Black attorney general; and Del. Brooke Lierman (D-Baltimore City) is the first woman elected comptroller.

“[For] Marylanders, especially young Marylanders, this will be the first time that they’ve been able to look at the executive branch of the state and actually see a makeup that is more reflective of the state,” Eberly said. “I think that matters in any representative government — for people to actually feel like they are part of that government.”

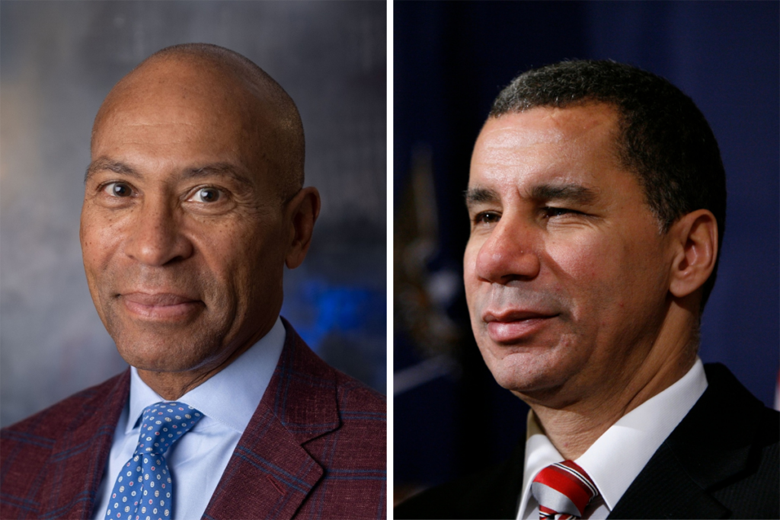

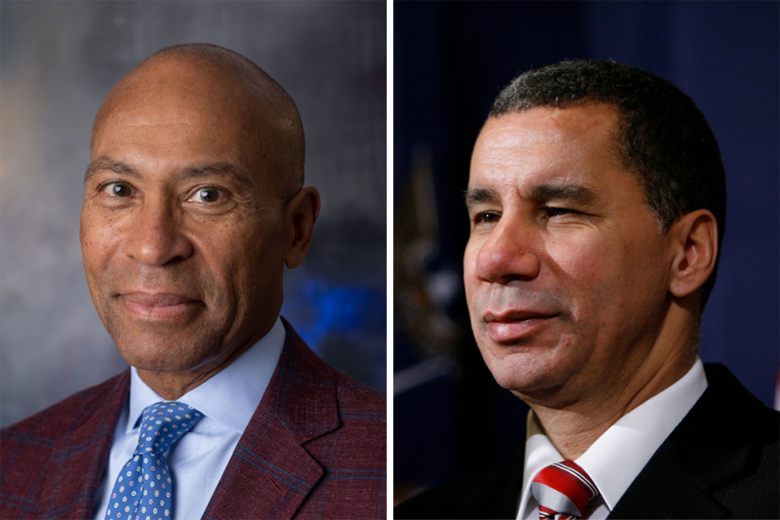

As for Moore, he is only the third Black person ever elected as governor across the U.S.. The first two were Doug Wilder of Virginia (who served from January 1990 to January 1994) and Deval Patrick of Massachusetts (January 2007 to January 2015). David A. Paterson of New York also served as a Black governor when he filled the remainder of the term of former Gov. Eliot Spitzer (D) from March 2008 to January 2011. Paterson had been elected lieutenant governor on a ticket headed by Spitzer, and moved up to the top job when Spitzer resigned in a sex scandal.

For the last 3 1/2 years, Paterson has worked as senior vice president for Las Vegas Sands Corp. The company is working to obtain three gambling licenses in New York.

In February, Patrick was hired as a co-director of Harvard University’s Center for Public Leadership. He’s also a professor of the practice of public leadership at the school.

Patrick and Paterson spoke to Maryland Matters recently to offer some perspective from their time in office and advice for Moore before he takes the oath of office in January as the state’s 63rd governor.

Wilder, 91, a distinguished professor at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, couldn’t be reached for comment.

‘Takes some time getting used to’

Patrick, 66, said he’s known Moore for 10 years, dating back to Moore’s time as executive director of the Robin Hood Foundation, an anti-poverty nonprofit organization based in New York.

Besides being Black, they share other similarities. Both were married with children and never held an elected office prior to voters choosing them as their state’s leader. Patrick had served in government as chief of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division during the Clinton administration.

Moore’s two children are 8 and 11 years old.

When Patrick campaigned for the governor’s office in 2006, both his children attended college out of state. His wife was a partner at a law firm.

Moore will have one substantial benefit that Patrick did not: he will have access to the governor’s mansion in Annapolis.

“There is not a governor’s residence [in Massachusetts],” Patrick said. “We had a house to manage and that was on our own. There is a governor’s residence in Maryland, so that may free up some time for Wes to focus more on his official duties.”

During his time as governor, Patrick said some residents wanted him to respond to local issues usually overseen by municipal leaders or other elected officials.

“There was a different level of expectation among the Black community because I was Black and because we ran a campaign that was very close to the ground,” he said. “That’s just one of the expectations that might be facing Wes.”

He told a short story about a Black mother from Roxbury, Mass., whose son died due to gun violence. The victim’s family asked Patrick to come out and offer support. He did visit the family and now they “have become quite close.”

Patrick said balancing his personal and public life also took some getting used to.

“It’s really hard. It’s hard to go out and be left alone. People were respectful. They were very sweet. They wanted to come up and photograph with us. It’s not like you could escape and have a date night in total privacy and anonymity,” Patrick said. “It takes some getting used to.”

He recommended focusing some policies within the governor’s office onto existing areas of interest or causes important to Moore’s heart.

During Patrick’s second term in 2011, he established Project 351, a youth leadership organization that focused on community service in which young people traveled to Boston once a year to celebrate the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. holiday.

The program remains in effect today, and recently eighth-grade students from all 351 municipalities in Massachusetts came to Harvard University to begin work as local ambassadors for their communities.

“I think the idea of community service is incredibly important for the served and the servant,” he said. “Service is not just something you do, but who you are. There are limits to the direct fund-raising you can do, but calling attention to those issues and showing up for their events while you’re in office were things that I tried to do. I’m sure Wes will be called on to do as well.”

‘Wouldn’t have this problem’

Paterson, 68, said he read Moore’s book, “The Other Wes Moore” after a recommendation from his sister-in-law.

“His story is just so unique and his commitment to second chances for people…he has a chance to be one of the great governors, leaving out that he’s a Black man,” Paterson said.

Paterson grew up in politics: His father, Basil Paterson, was a prominent Harlem politician who served several key roles in New York state and city government and was also the first African-American elected vice chair of the Democratic National Committee. David Paterson spent 20 years in the state Senate before being elected lieutenant governor, and was the top Senate Democrat for several years.

Both Paterson and Moore share some celebrity status.

Paterson’s claim to fame came during an appearance on NBC’s “Saturday Night Live” in 2013 when actor Fred Armisen portrayed Paterson, who’s also legally blind.

During the skit, Paterson said, “You have poked so much fun at me for being blind that I forgot I was Black.”

“’Saturday Night Live’ lampooned me every week. The guy would walk into doors. Hold maps upside down. It was really degrading,” Paterson said. “My staff wanted me to laugh along and go on the show. My point is that there a number of African Americans and a number of people who are disabled. While people are laughing, internally, they actually think this is how disabled people are.”

Moore will likely face acts of racism, but Paterson said it helps to consider someone’s motivation in those moments.

Paterson recalled once stepping off a plane and a security guard asking him where was the governor — three times.

“Then it hits him, ‘Oh, you’re the governor?’ ‘Yes, for the third time,’” he said. “I didn’t see this as racist. He just wasn’t used to seeing a Black governor. This is something that hasn’t happened in the regular course of business. If this was the regular course of business with at least five of the 50 governors are Black, or even a Black woman, then we wouldn’t have this problem.”

In terms of raising a family while serving as governor, Paterson said his wife worked for the insurance industry and his daughter attended college while he was in office. His son, who was 14 at the time, was most affected.

Paterson recalled a time when his son was with some friends at a pizzeria and disputed a bill.

“One of the other kids says to the general manager, ‘You better listen to him because if you don’t, his father may shut your pizzeria down,’” he said. “The owner of the pizzeria goes to my son’s school, to the principal’s office, and complains about my son. …How is my son going to know what [his friend] is going to say? It was totally out of line.”

In protection of his son, Paterson said he traveled to the pizzeria with four state police officers.

“I have to admit, this is the only time I did it when I was governor,” he said. “I said to the owner, ‘If you ever treat my son that way again, I will shut this shack down.’ I turned and walked out.”

The advice for Moore as a parent: “You want to protect your kids. They are going to grow up in [public life]. Make sure they are safe.”