This article was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

As they entered 2018, operatives for Gov. Lawrence J. Hogan Jr.’s reelection campaign were blessed to have a candidate with durable popularity, unrivaled political instincts and a robust war chest.

But they still knew he could lose.

Polls that showed the Republican incumbent with astronomical popularity also showed him below 50 percent in hypothetical reelection matchups against a generic Democrat as well as some of the real Democrats who were competing to take him on – a potential danger signal for any incumbent. And Hogan’s people knew that President Trump was going to spark a big backlash against all Republicans – and create a surge of Democratic turnout in Maryland.

When election results came in across the river in Virginia last November, the landscape simultaneously became more challenging and more clarifying: Hogan’s campaign strategists saw exactly how he could lose.

“It helped crack the code,” Jim Barnett, Hogan’s campaign manager recalled in an interview last week. “It helped us prepare for an over-turnout universe.”

Polls had shown the 2017 Virginia gubernatorial election as a see-saw battle between Democrat Ralph Northam and Republican Ed Gillespie – who Hogan championed and campaigned for. The very last polls in fact suggested the momentum was with Gillespie.

But on election night, Northam scored a stunning 9-point win, and Democrats made dramatic gains in the House of Delegates. Their victories were propelled almost exclusively by moderate-to-liberal suburban women – Democrats and independents – who turned out in record numbers. They were angered by Trump’s harsh rhetoric and positions and attached some of the same characteristics to Gillespie and other Republicans, fairly or not.

As a result, Hogan strategists said, they knew their goal for the rest of the campaign was to appeal to key Democratic and key unaffiliated voters – especially women.

“They became the centerpiece for all voter contact,” Barnett said.

A data analytics firm, he said, helped the campaign model the electorate, based on certain voters’ likelihood to vote – and their likelihood to approve of what the governor was doing.

The Hogan forces believed they had a solid base to build from.

Since he had been governor – in fact, even before he was elected in an upset in 2014 – Hogan worked assiduously to project a bipartisan image. Change Maryland, the organization he set up to criticize the policies of his predecessor, former Gov. Martin J. O’Malley (D), and tee up his own campaign, was driven as much by Democrats and independents as by Republicans.

As soon as he was elected, Hogan visited Comptroller Peter V.R. Franchot (D) in Franchot’s office, and the two went holiday shopping together with their wives. At his inaugural address, Hogan went out of his way to criticize political extremism of all stripes.

“Too often, we see wedge politics and petty rhetoric used to belittle our adversaries and inflame partisan divisions,” he said on that snowy January day. “But I believe that Maryland is better than this. Our history proves that we are better than this.

“It is only when the partisan shouting stops that we can hear each other’s voices and concerns. I am prepared to create an environment of trust and cooperation, where the best ideas rise to the top based upon their merit, regardless of which side of the political debate they come from.”

The message wasn’t just reassuring to broad swaths of the Maryland electorate – it also helped Hogan set the tone for his first term. And that proved particularly useful following the presidential primaries of 2016.

“It was almost eerie, because it laid out almost two years in advance what Trump was about,” said Douglass V. Mayer, who was communications director for most of Hogan’s first term before becoming deputy campaign manager for his reelection.

Building the brand

Hogan had a tumultuous but ultimately successful first year.

He won plaudits in most corners for the way he handled the riots in Baltimore City following Freddie Gray’s death in police custody, and he won universal praise for his candor, fighting spirit and good humor following his cancer diagnosis. By 2016, Hogan was working hard to draw contrasts between himself and Trump – skipping the Republican National Convention in Cleveland and writing in his father’s name for president that fall.

Even though he’d clash with Democrats on some policy issues, Hogan was always quick to say he placed a premium on “bipartisan, common-sense solutions,” and would often embrace – some critics would say appropriate – Democratic ideas.

But that charge never concerned Hogan’s strategists. It helped Hogan build a brand – as an unconventional Republican, an anti-Trump, in an era when more and more Republicans were marching in lockstep with the president. Democrats’ efforts to tie Hogan to the bombastic Trump largely went nowhere.

“Everything we did in the campaign was to promote, distinguish, defend and protect that record,” Mayer said.

The voters took notice – and clearly approved. Hogan’s popularity rose to levels all politicians would envy – approval ratings in the 60s and, ultimately, the 70s. For several quarters running, he was the second most popular governor in the nation – behind another Republican in a blue state, Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker, who is considered even less of a partisan than Hogan.

Political campaigns use focus groups regularly. Generally, these are groups of 10-12 undecided voters who meet in a room and discuss, with a facilitator, the issues that are on their mind and the traits they are seeking in a political leader.

To reinforce their outreach to moderate and liberal women, the Hogan campaign devised a focus group on steroids. Beginning in May, they convened 110 women who were generally supportive of the governor but not necessarily committed to his reelection during online chats. The group would meet electronically every few weeks, and after Labor Day, the sessions took place every two weeks.

“It wasn’t necessarily to persuade these women to vote for the governor,” Mayer said. “It was more to keep an eye on the state of the race, to see what was influencing voters like that.”

One surprising thing the campaign discovered was that Hogan’s claims that he had make record investments for education didn’t necessarily resonate. But at the same time, the women didn’t believe or embrace Democratic nominee Benjamin T. Jealous’ promises to boost public school spending and give teachers a substantial raise.

“They don’t believe what anybody says about that issue,” Mayer said.

Sizing up Jealous

Hogan campaign strategists did not feel supremely confident, following the Democratic primary for governor, which Jealous, the former NAACP president, won over more experienced politicians with surprising ease. Jealous had put together a solid combination of minority and progressive white voters, fueled by organized labor and the Maryland remnants of Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders’ political operation. He won 22 of the state’s 24 jurisdictions in the primary. An independent expenditure campaign, unaffiliated with Jealous’ operation but funded by labor and out-of-state progressive donors, also helped.

“This was no slouch,” Mayer said.

“Clearly, given the national environment, you’re nervous,” Barnett added.

Unlike some of the other Democratic candidates, who had records in public office to scrutinize, Jealous was a bit of an unknown, which made it harder for the Republicans to plot strategy against him.

“We’ve got to figure out what to do with this guy,” Mayer recalled the governor’s campaign team thinking. So they dug into his campaign promises – like Medicaid for all, a $15-an-hour minimum wage, and greater school funding – and tried to calculate what they’d cost.

The Hogan campaign prepared a four-month plan for television advertising, carved into two-week segments, that began almost immediately after the June 26 primary. Some were biographical spots about the governor. Others focused on certain issues. Others highlighted the cost of Jealous’ campaign promises, by the Hogan camp’s calculations.

Those spots, along with Republican Governors Association TV ads blasting Jealous as untested, risky and unreliable, helped define the Democratic nominee to a broad swath of voters who hadn’t been paying much attention to the election up until that point. To the amazement of Hogan’s team – and most everyone else following the race – the Republican ads basically went unanswered for more than two months. The Jealous campaign did not start airing ads until well after Labor Day, and even then he was on the air far less often than Hogan.

Jealous also suffered some self-inflicted wounds – dropping an F-bomb on a Washington Post reporter at a news conference, declining to attend the popular Maryland Association of Counties summer conference in Ocean City, stumbling during an MSNBC interview. None was fatal – or even registered much with the public. But they did keep the Democrat’s campaign off-balance, and they kept the chattering classes chattering.

Over and over during the course of the general election, Hogan’s team members would ask themselves: Who won the day? Who won the week? Who won the month? They rarely tallied any losses.

Fretting Kavanaugh

Barnett said the inflection point for him came in late August, when the latest campaign finance reports showed that Hogan had about $9 million in his campaign account compared to just $250,000.

“I didn’t know what it was going to look like,” he said. “It was going to tell us what the trajectory of the rest of the race was going to look like.”

At that point, it became difficult for the Jealous campaign to reverse the narrative that it was broke and outgunned. What’s more, polling showed that Hogan was getting close to a third of the Democratic vote and close to a third of the African-American vote. That suggested to Hogan’s advisers that he could survive a blue wave.

Even so, the campaign had one last mini-scare – and it had nothing to do with the race itself. After the bitter political fight over Supreme Court Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh’s confirmation in late September and early October, Barnett said he worried whether there would be fallout among women voters that would scorch the governor.

But the Kavanaugh confirmation seemed to motivate and mobilize voters across the political spectrum, and the Hogan team came to realize that their candidate would not suffer any consequences.

“Voters are a hell of a lot more sophisticated than talking heads give them credit for,” Mayer observed.

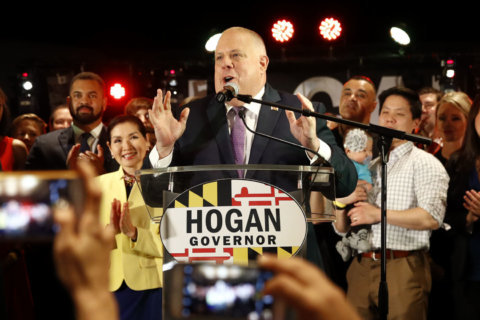

And from them on, the Hogan campaign felt reasonably secure, despite some last-minute jitters that affect even the most well-oiled campaigns. But in the end, those were unfounded: Even with a blue wave across most of the state, Hogan prevailed by almost 12 points – becoming the first Republican governor to win reelection in Maryland since 1954.

“Everything we did on the campaign, everything the staff did in the governor’s office, none of the tactics would have mattered worth a damn if the governor hadn’t established his own strategy and a brand from the outset,” Mayer said.

Postscript: On Election Day, the 110 liberal and moderate women the governor’s campaign regularly convened split evenly between Hogan and Jealous.