WASHINGTON — A “worst-case scenario” domestic murder-suicide that orphaned three children has Maryland’s top prosecutors debating whether there should be a change in the law to confiscate an accused abuser’s weapons.

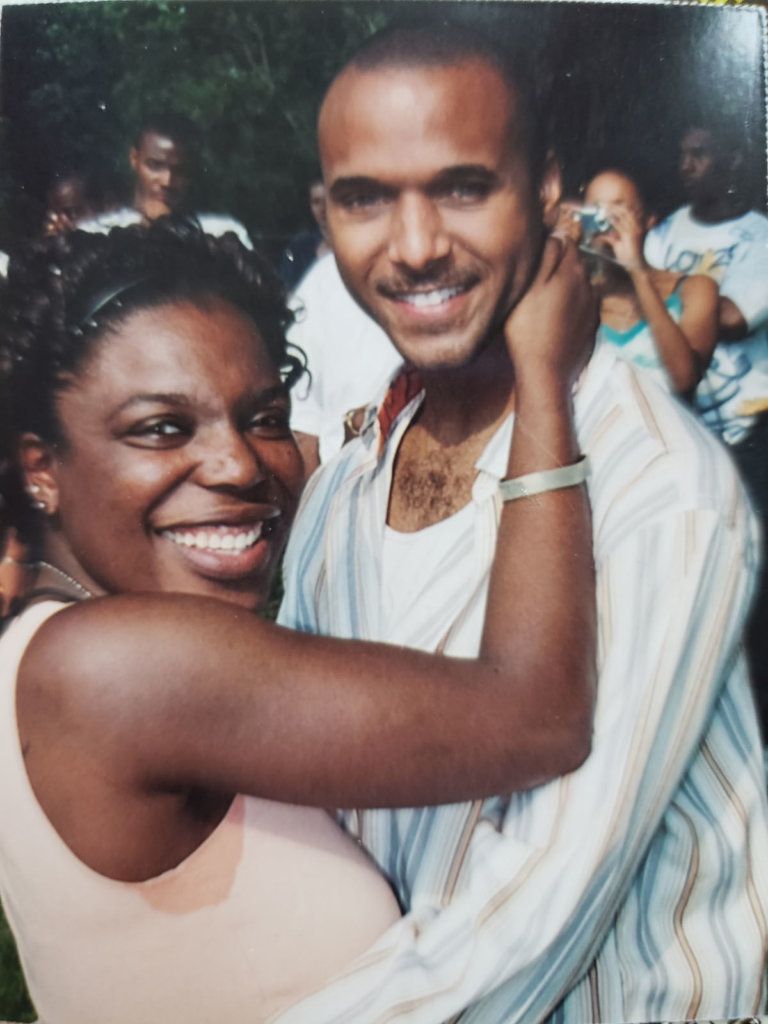

Candace Carnathan’s worst fears were realized on Jan. 27 when the mother became the victim of a domestic murder-suicide. Charles County investigators said her husband, Calvin, shot and killed her just hours after he was served a protective order.

Their 10-year-old son called 911 after his father told him to, he told dispatchers in the emergency call obtained by WTOP in a public information request. His family encouraged WTOP to publish the 911 call, which they believe will highlight the problem of domestic violence.

During the call, the boy told the dispatcher a fact the courts already knew about his family.

Dispatcher: “Does your mom and dad have guns?”

Boy: “Um, I think only dad does.”

Dispatcher: “You think your dad does?”

Boy: “Yeah.”

On her temporary protective order, court documents show, his mother marked in three places that her husband owned a shotgun.

Domestic violence makes up quarter of Charles Co.’s docket

“When a victim says, ‘I need help,’ that’s by far the most volatile time,” said Charles County State’s Attorney Tony Covington. Domestic violence cases, he said, make up a quarter of the criminal docket in his county.

“I agree, as far as taking guns from people in this situation. It’s a temporary thing. It’s absolutely worth it,” Covington said. He went on to reference Calvin Carnathan returning to his home hours after being escorted from the house by a Charles County sheriff’s deputy, who served him a protective order.

“When he comes back after a few hours, he’s clearly demonstrating he’s not going to comply with that piece of paper.”

And without resources to support victims in the middle of the night, more shelters for them to go to or someone the county makes available 24/7, Covington said pulling the firearms from the situation has to happen.

However, there is a question of the alleged abuser’s rights.

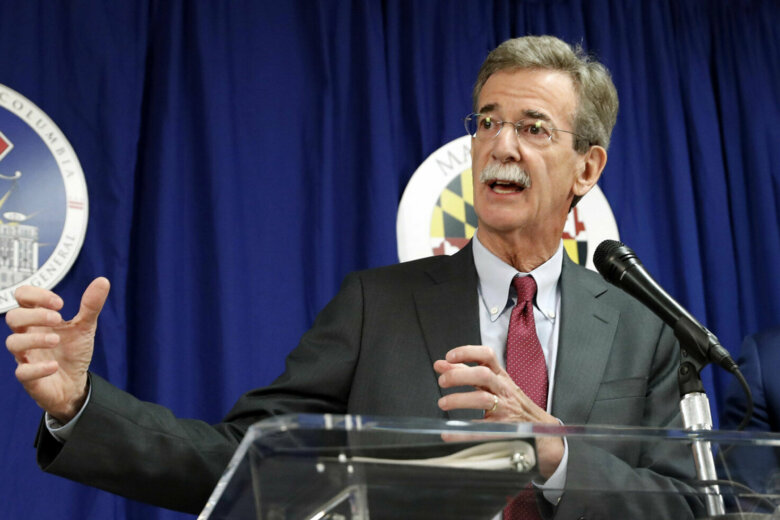

“There needs to be some kind of protections for the accused. But they need to be accomplished quickly, and I think we can do a better job of that in our state,” Maryland Attorney General Brian Frosh said on striking a balance between victim safety and gun owner rights.

The Carnathan’s three children — aged 11, 10 and 7 — have been adopted by their aunt. But their family believes the loss of their parents could have been prevented.

“People don’t just talk about guns in their protective order if they don’t feel like the person is a danger to themselves or to other people,” said Candace’s sister, Sydney Miles.

‘Don’t wait 7 days’

Speaking briefly about the psychology of a domestic violence victims’ tendency to hide the reality of abuse, to protect themselves or their children, Miles believes that there should be more sensitivity given to victims who take the step to seek help.

She said she thinks the law should change so judges must order that known firearms be confiscated from the accused when a protective order is issued, instead of having the discretion to wait and hear from both parties.

“Don’t wait seven days. You don’t know what’s going to happen in seven days. It didn’t even take him 24 hours,” Miles said of her brother-in-law’s actions.

The amount of time between when a protective order is issued and when both parties meet in front of a judge depends on the type of order — temporary or interim — and specific mandates the judge may add.

Covington supports the need for stronger legislation to pull firearms out of a domestic violence situation well before an accuser is convicted. A bill to confiscate firearms from felons convicted of domestic violence offenses is making its way through the Maryland legislature.

However, Covington said, government intervention is needed sooner for victims’ safety.

“The legislative fix is that we should take weapons out of the home, period … and at the permanent protective order hearing where both parties are present, the court can decide whether to maintain the seizure of those weapons,” Covington said.

Mandating a judge confiscate someone’s property — their weapons — based on an accusation of only one party is why the court leaves it to a judge in Maryland to assess if the situation warrants weapons seizure.