WASHINGTON — For most people, one wrong step at the wrong time might lead to a sprained ankle at worst. Cedric King took one wrong step and woke up eight days later, half a world away, and without his legs.

It was 2012, and King was a master sergeant who was 17 years into his Army career and well into his second six-month deployment in two years after spending 2003 in Iraq. “Long story short,” he said, leaving out the machine-gun fire that was raining down on him, “I end up stepping on 30 pounds of explosives and it ripped both of my legs off.” His right arm and hand were injured too.

“To be honest with you,” King, 41, told WTOP recently, “that’s where the story took a turn for the best.”

“Now I’m not saying having legs is a bad thing, and not having legs is a good thing. But for me personally, that was my reckoning moment. That’s the moment where I felt like things came together for me … forced me to find out who I really was on the inside, and find out how strong and courageous I could be under some serious circumstances.”

King said he had to adopt that mindset if he wanted to survive.

“But the other part of it is, you have to find out who you are,” he said. “There are so many people out there today who are powerful beyond belief but just haven’t figured out who they are and how strong they are because life circumstances provide them with safety.”

As King or any other soldier can attest, there’s no safety in combat. But he’s learned how to channel the adversity he still faces every day into something that makes him stronger and causes him to “love deeper.”

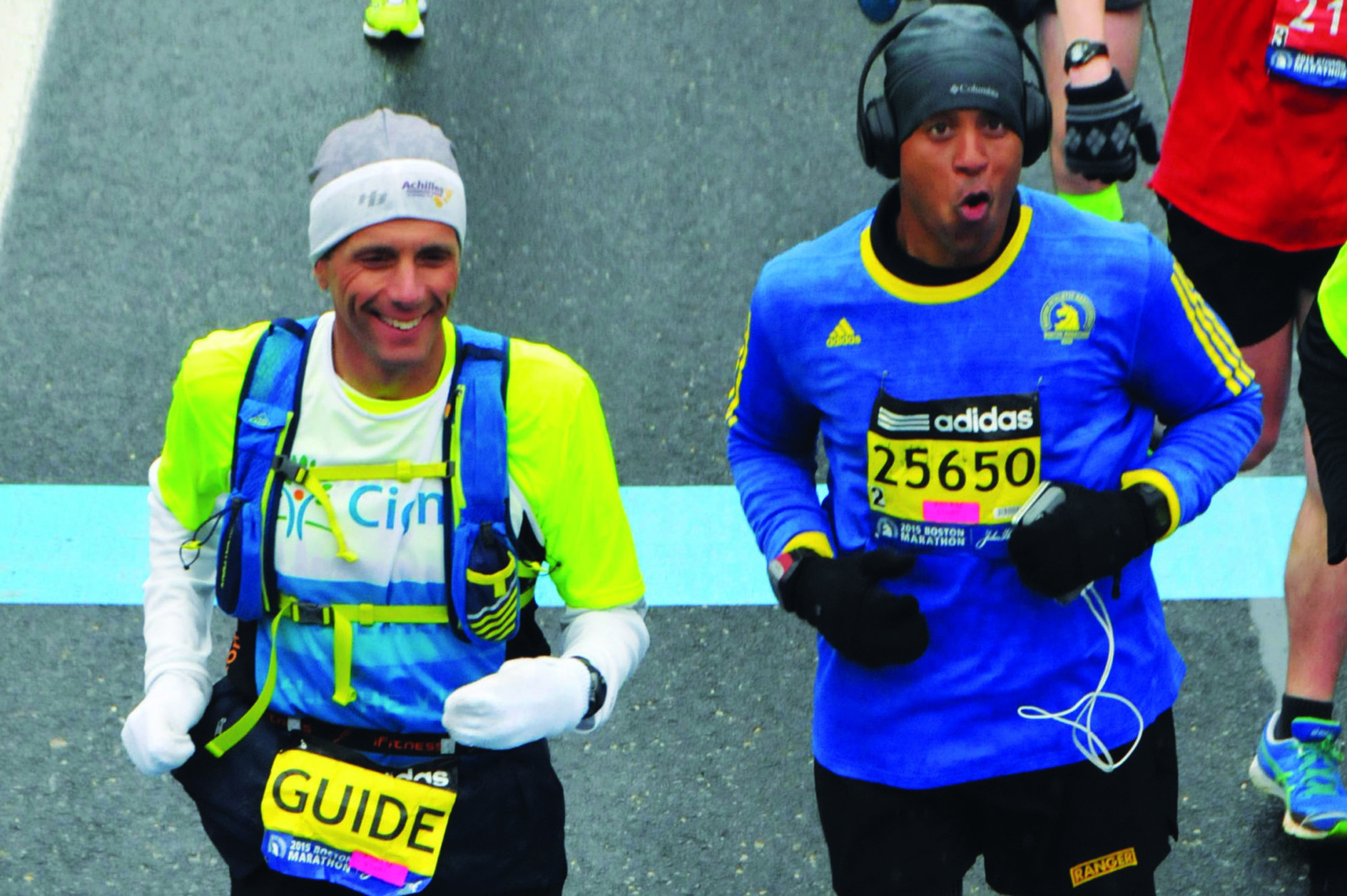

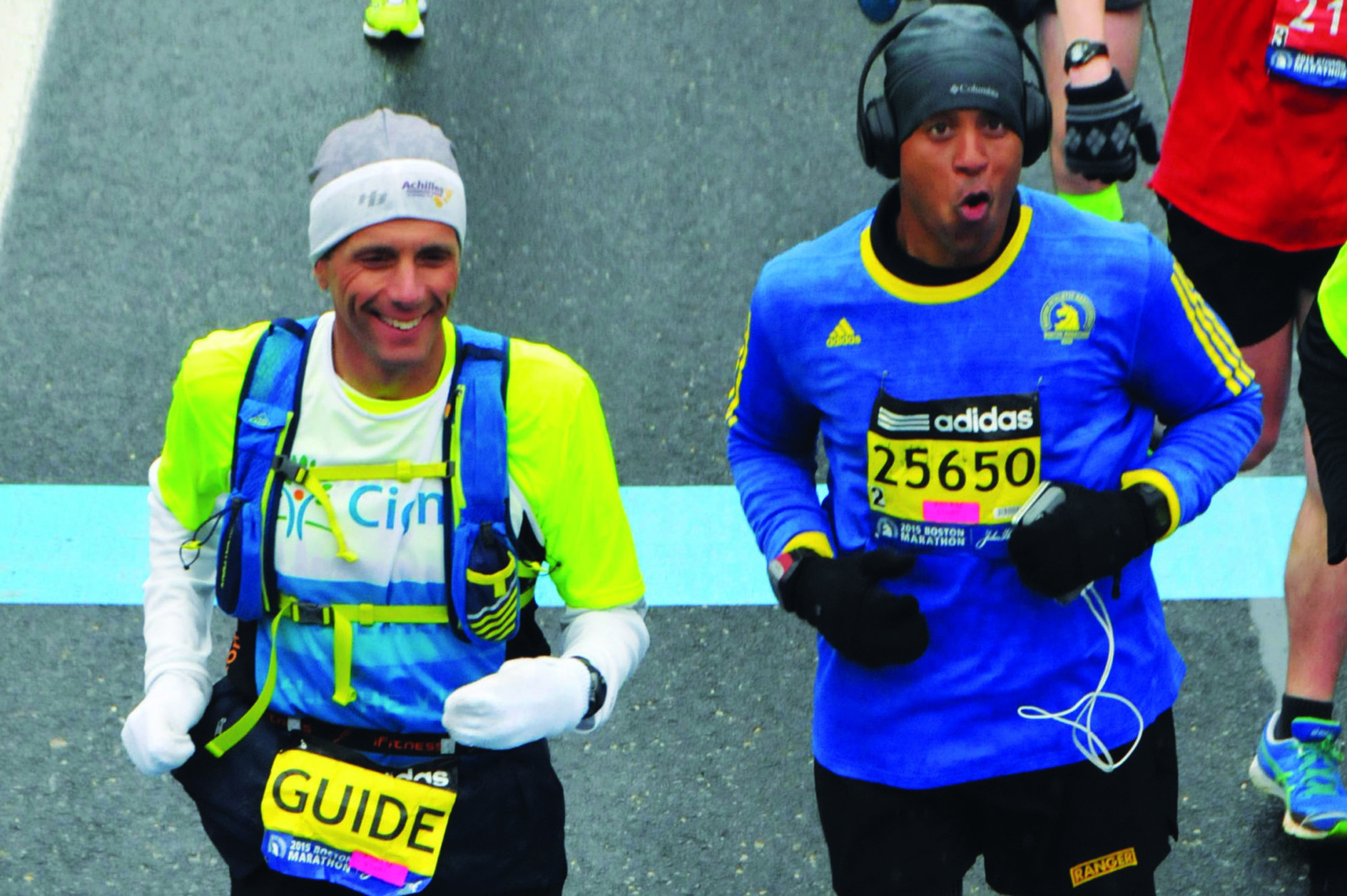

King won’t be running the full Marine Corps Marathon this weekend. This time around he’ll be hooking up his prosthetic legs to run the MCM 10K, though he has run marathons and even climbed mountains since losing his legs. He’ll be joined by friends, some of them also wounded veterans, who have formed what’s known as a “micro community” with him. It’s a group that, during the toughest of times, helps each other to rally ahead in dark moments.

‘Every step is closer’

“We’re not going to be running it any different,” King said. “I say it like that because there’s a struggle for each of us. For me, my struggle is the legs. For somebody with legs their struggle may be the heat, or their struggle may be the distance, or whatever it is. We’re all runners.”

He pushes through by keeping in mind that “every step is closer than the last step…

“I look at it as, it’s one step at a time and that’s something that everybody can do. I can always put one prosthetic in front of the other. Forget about the long game. Forget about the distance…

“You may not be able to imagine another mile. But you can imagine another foot step. And if you can imagine another foot step, then guess what? Continue to do what you can do.”

That type of thinking, he acknowledged, has allowed King to move ahead with his life as well as racing. But it took years of rehabbing in Bethesda to get there — years in which he had to relearn a lot of things he called “the basics” — stuff he’d been doing since he was an infant.

“Doing things like learning how to walk again, and learning how to write again, and learning how to run again … learning how to drive again,” said King, “I had to learn how to do all over again in those three years.” He was in his mid-30s, so the difficulties and failures involved in the process wounded his pride as well, and you can hear the lingering frustration in his voice sometimes.

“It is really tough learning how to walk and climb stairs again when you could do it effortlessly,” he conceded. “Maybe the toughest part was falling down all the time with the prosthetics. I think that was really the toughest part. Walking and falling down and having everybody look at you and help you back up, and falling down again and again. That’s — that can be mind-numbing. It can be a lot more than what a lot of people sign up for.”

‘Get back up’

Today, Cedric King goes around giving transformational speeches meant to encourage people to get back up again. That can be the hardest part.

“What I found is, it’s not the falling down that really breaks your heart. It’s the effort to get back up,” King said.

And since he’s run races on prosthetics before, he knows he’ll probably topple over and take some stumbles along the 10K track.

“If you stay down a second more than you have to, it has a tendency to keep you down longer than what you anticipated,” said King. “The falls — you’ve got to hurry up and get back up again,” he said with a snap of the fingers.

It’s at this point in the conversation that you start to wonder whether he’s still just talking about the race.

“You’ve got to hurry up, even if you don’t feel like it … you’ve got to get back in the game of life. Because if you take just a second more than you need, I’m telling you, you’ll be there a lot longer than you planned to be. And I know that, I know that. I’m speaking from experience right now…

“You’ve got to get back up as soon as possible. Even if you don’t feel like it, even if you don’t think there’s anybody that cares, you owe it to yourself to get back up. That’s what learning to walk and falling, and learning to walk and falling, and falling and falling and falling again, has taught me.”