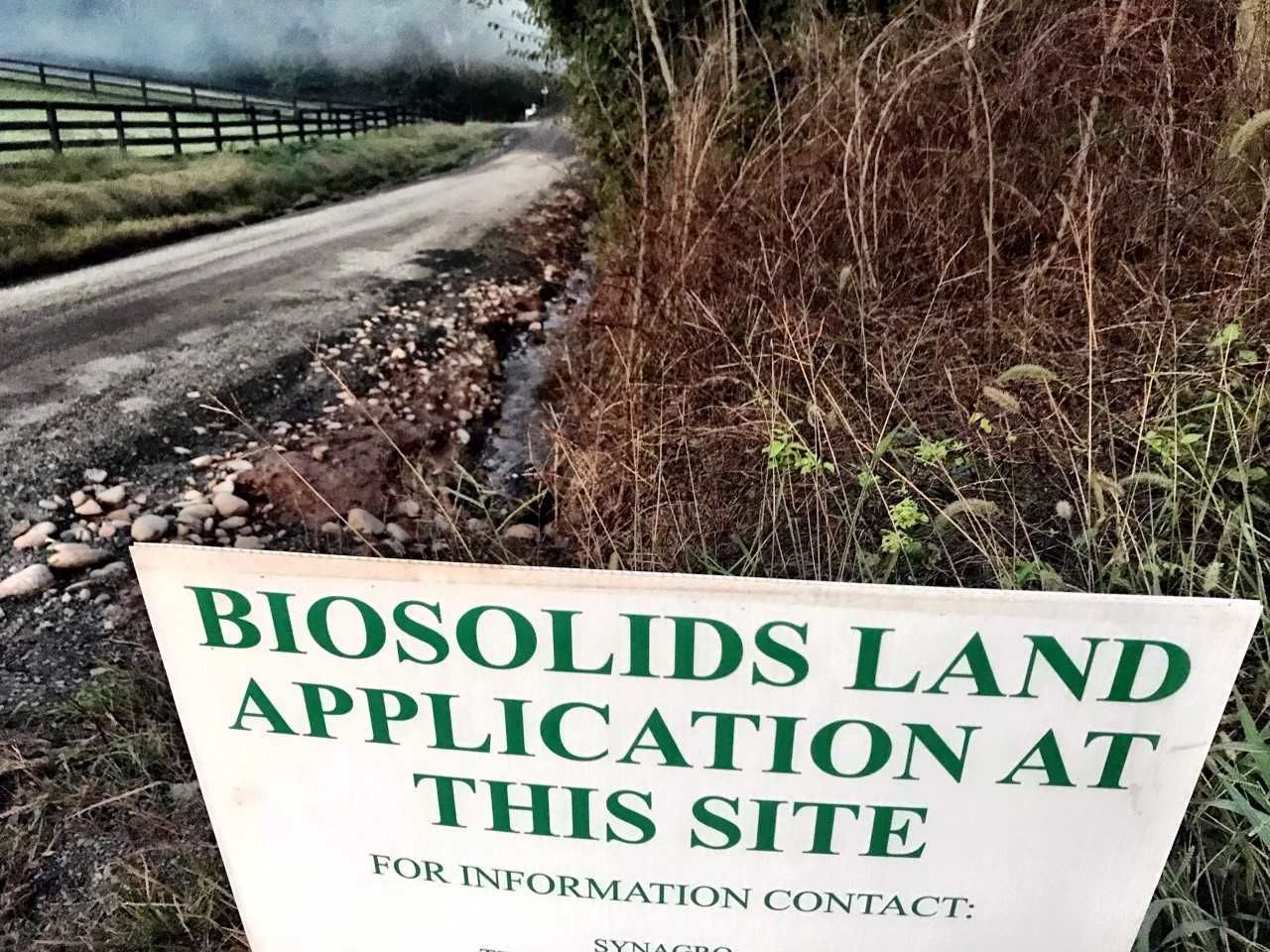

LEESBURG, Va. — The stench of human waste in farm fertilizer has raised complaints from neighbors in Loudoun County and has prompted the board of supervisors to seek how it can have more control over the use of biosolids.

Biosolids are made from treated sewer sludge — the solids and liquids from toilets and drains.

Mike Deeben, of Lucketts, said a neighboring farm on Spinks Ferry Road, recently used tons of biosolids as fertilizer, which is affecting his family’s life.

“The flies were relentless inside the house,” Deeben told WTOP. “We had fly strips all over the house.”

Deeben said he was “held hostage” inside his home, immediately after the September biosolids application because of the odor. He said his dog suffered stomach distress from drinking water from runoff of the treated farm.

In Tuesday night’s board of supervisors meeting, Chairwoman Phyllis Randall expressed disgust at the smell and health risks being posed by biosolids and said the panel would discuss ways for the county to have more control over its usage.

When wastewater arrives at a treatment plant, the solids are separated out and becomes sewage sludge.

According to the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, “Class A biosolids receive a level of treatment that virtually eliminates disease-causing organisms and pathogens.” Class A biosolids can be sold to homeowners and are sold in garden stores.

Class B biosolids receive some treatment, but have higher levels of detectable pathogens than Class A biosolids.

Use of Class B biosolids requires a permit from Virginia’s DEQ.

The Class B biosolids are cheaper, and are used far more often than the cleaner version, according to Virginia’s DEQ. However, between 2008 and 2013, biosolids were used on less than 1 percent of permitted application sites in Virginia, dwarfed by commercial fertilizers.

The agency said Class B standards “are considered to protect human health and the environment as well as Class A biosolids standards when coupled with specific application restrictions, such as distance between land with biosolids and any wells and streams, access restrictions for people and livestock, and certain crop exclusions.”

Dr. David Goodfriend, director of Loudoun County’s Health Department told supervisors that DEQ oversees where Class B biosolids can be applied — at least 100 feet from a neighbor’s property line.

However, according to Goodfriend, setback distances can be extended beyond 400 feet if he, as the local Health Department director, determines it is necessary to prevent specific and immediate injury to a person.

Randall said she wanted to consider legislation that would enable the county to play a larger role in the regulation and usage of Class B biosolids within the county, and requested it be discussed in the board’s next meeting.