On the third floor of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in D.C. is a blue and mint-green dress adorned with rhinestones and sequins. The dress was worn by a tennis legend 50 years ago who set out to prove that the “fairer sex” stood on equal footing with men and deserved fair pay.

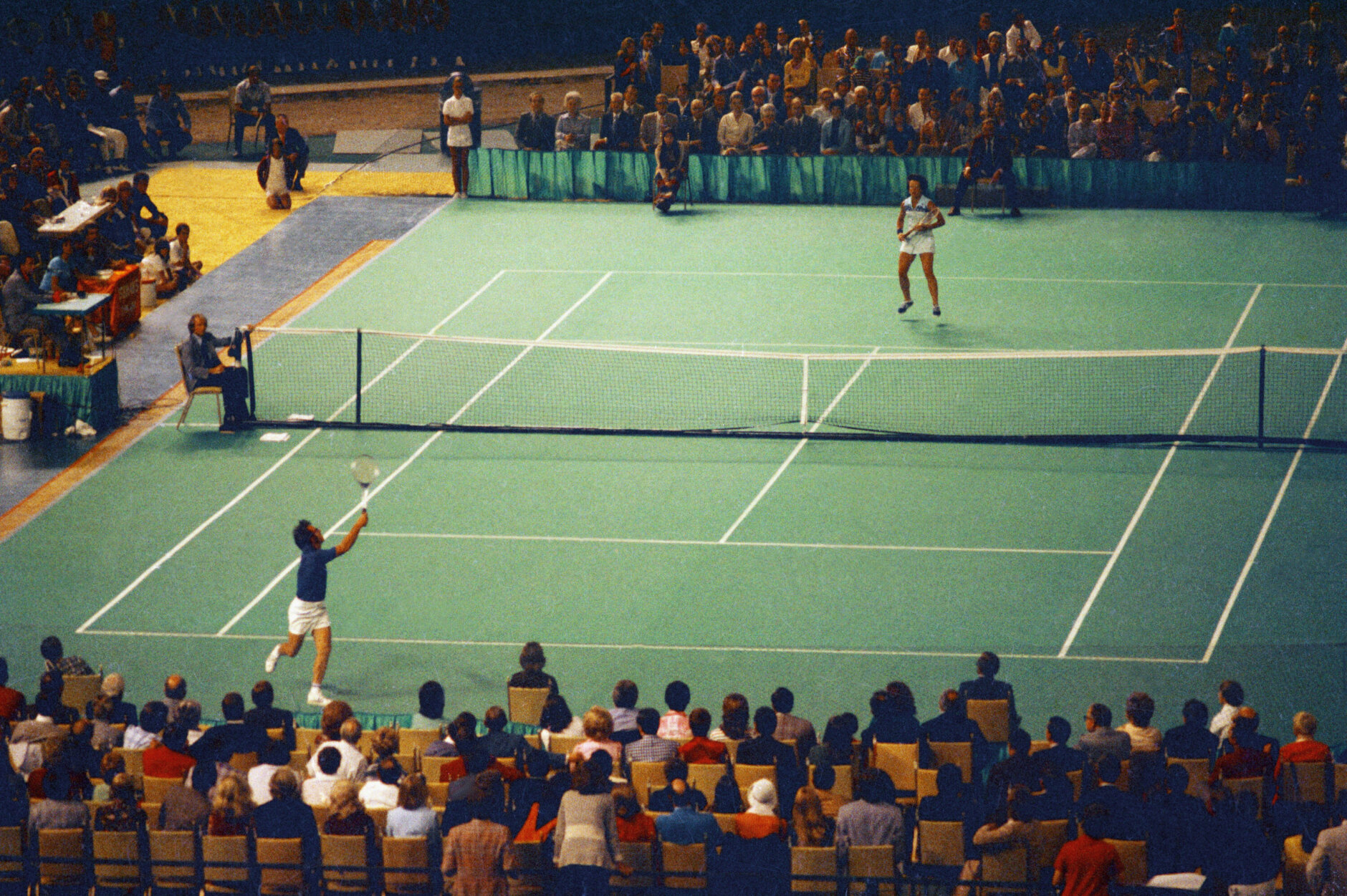

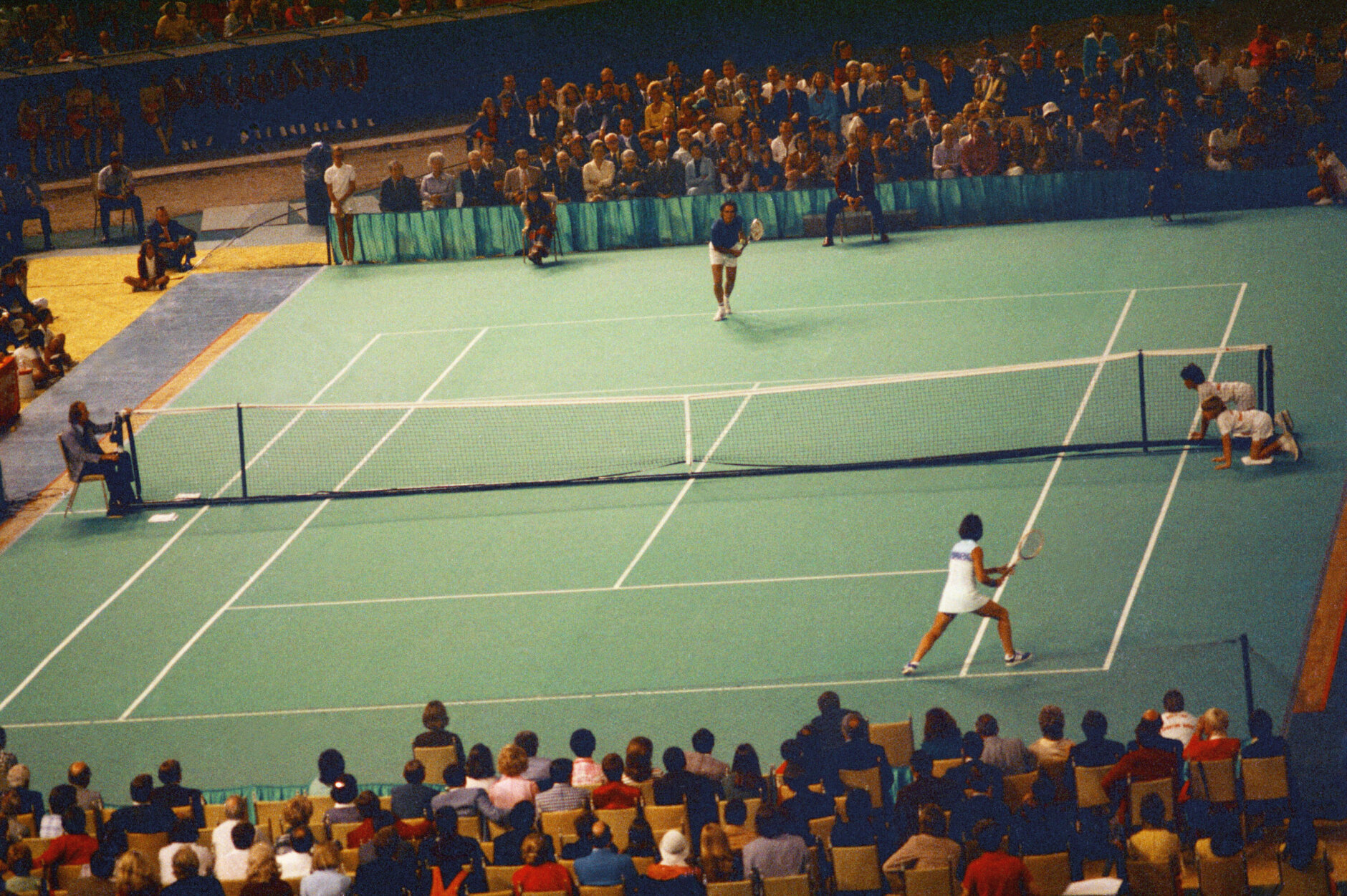

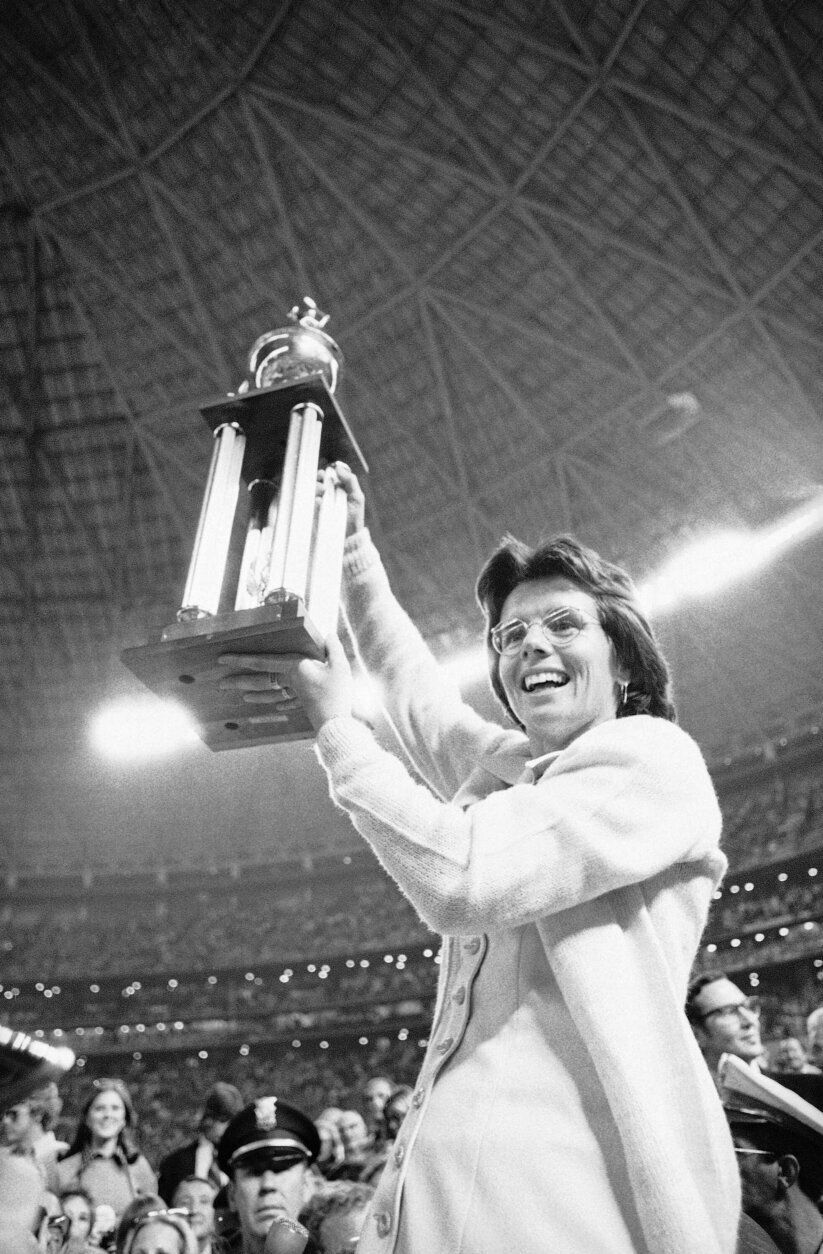

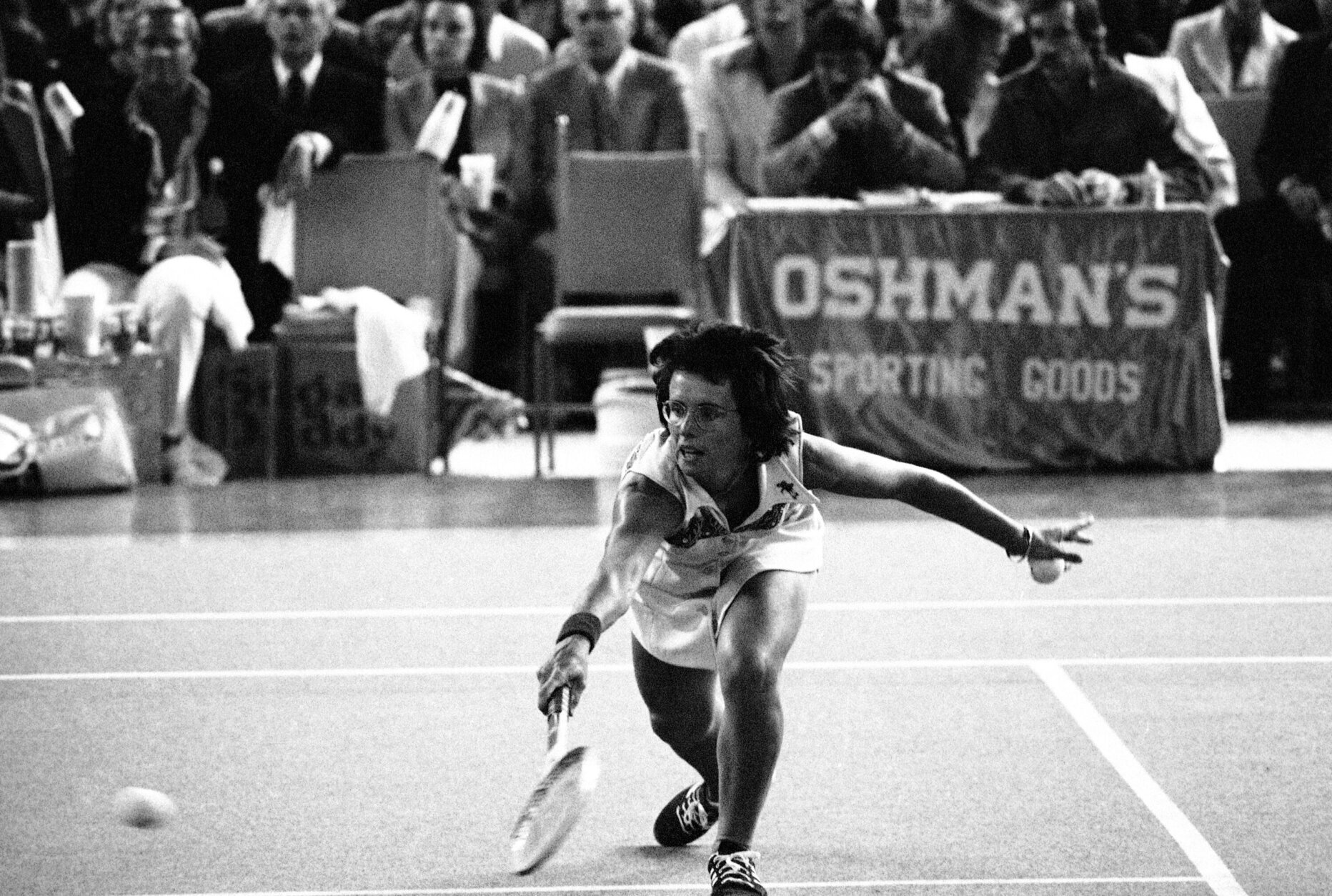

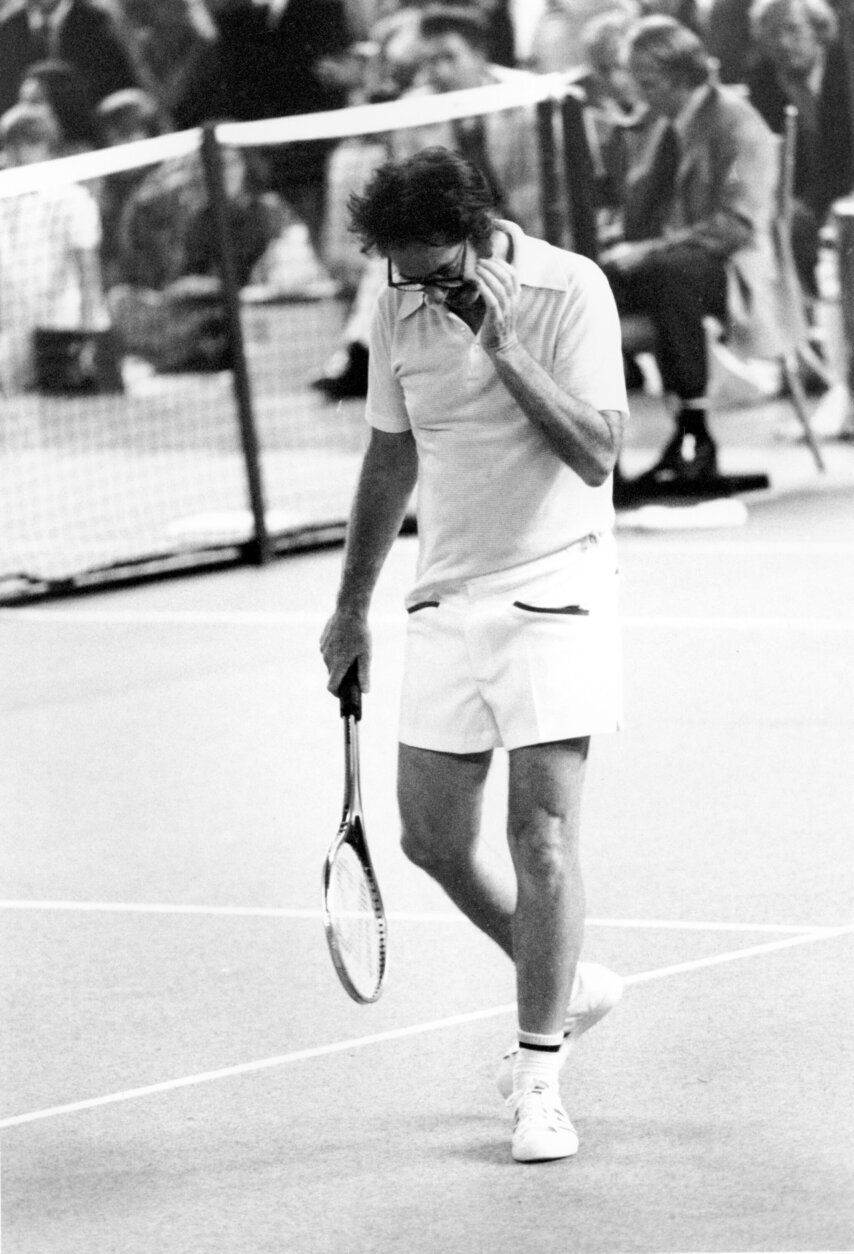

It’s the dress tennis champion Billie Jean King wore during the second “Battle of the Sexes” — an exhibition match on Sept. 20, 1973, between King, then 29, and Bobby Riggs, then 55 years old. King easily won the match in three sets 6-4, 6-3 and 6-3.

Fifty years later, the match still stands as an important symbol of women’s struggle for equal pay, and it is still “one of the most important moments in the history of our sports culture,” according to sports journalist Christine Brennan.

Spectacle or sport

Critics have argued that King, who was in her prime at 29, was not an equal match for Riggs, a former No. 1 and a self-described “male chauvinist pig.”

Riggs threw more fuel to the fire with comments that women’s tennis was night and day compared to the men’s game, but “you can see some pretty legs.”

Although no longer in his prime, Brennan said that Riggs was still a decent tennis player, even at 55.

“Let’s not use that to minimize one of the most important developments in the history of girls and women in sports,” Brennan said.

Riggs had earlier played Australian tennis player Margaret Court in another “Battle of the Sexes” and beat her easily, but he was always “buzzing around Billie Jean, asking, ‘Could he play tennis against her?'” Brennan said.

When Court lost against Riggs, Brennan said that’s when King realized that she would have to take him on — and she would have to beat him.

During this time, King had also been lobbying for equal pay for female tennis players, threatening to not play at all the following year after winning the U.S. Open in 1972, where she earned $10,000 in prize money — $15,000 less that the male winner Ilie Nastase, The Associated Press reported.

Just a year prior to the “Battle of the Sexes,” President Richard Nixon had signed the Education Amendments of 1972, legislation that prohibited sex-based discrimination in school programs that received federal funding, commonly known as Title IX.

Brennan said that with Title IX then only recently signed, women’s and girls’ sports and “any sense of equality and opportunity for girls and women in sports was really hanging by a precarious thread.”

“While Title IX and the ‘Battle of the Sexes’ really had nothing to do with each other, they also had everything to do with each other,” Brennan said.

‘Glued to the television set’

“We sometimes forget that women were not allowed to vote until 1920,” said Eric Jentsch, curator of entertainment and sports at the National Museum of American History. “So the ‘Battle of the Sexes’ took place a little over 50 years from that, a time when many were continuing the fight for equal opportunities in all aspects of life, whether in school, the home, or in the workforce.”

Jentsch said the “Battle of the Sexes” put some of these struggles on the tennis court, before the eyes of millions of viewers.

Brennan was just a teenager in Toledo, Ohio, when the match took place, and she said she remembers sitting on the couch in the family room and “everyone’s just glued to the television set.”

“It was the first time I’d ever seen a woman [on] equal footing with a man in a sports event. First time I’ve ever seen a man and a woman being treated equally on a stage, whether it’s sports, politics, anything in our society,” Brennan said. More importantly, it was the first time she had ever seen a woman beat a man in anything.

“It wasn’t a meaningless exhibition. It was one of the most important moments in the history of our sports culture,” Brennan said.

“Pressure is a privilege” has been King’s motto, and it’s also the title of the book she wrote with Brennan, who said that King felt the pressure of the event.

“But she also said it was a privilege for her to be able to have that opportunity to carry that mantle and to easily defeat Bobby Riggs in three sets,” Brennan said.

King was also referring to the opportunities to lead and to change society, which are not easy things to do.

“There’s a lot of pressure on your shoulders; there are people expecting things from you and be able to thrive during that time is obviously the trait of a champion,” Brennan said.

More work ahead for equal pay

In 2023, the U.S. Open marks 50 years of giving out equal prize money to its women’s and men’s champions — the first sporting event in history to do so, according to the US Open website. It credits King for being the pioneer in demanding equal pay for players.

“No individual has done more to secure equality for female athletes than Billie Jean King,” Brian Hainline, USTA chairman of the board and president, said in a statement.

Other sports have been slower to follow. The U.S. Soccer’s men’s and women’s national teams just last year signed historic collective bargaining agreements over equal pay, The Associated Press reported. And the NBA and the WNBA is not even close, Brennan said.

Brennan credits, in part, the effects of Title IX for the U.S. soccer agreement.

“The men on the U.S. national team decided they would give up some money, so those women could have equal pay,” Brennan said.

Men raised in the age of Title IX who have grown up alongside girls or women playing in the same court or field, have a greater sense of respect for girls and women playing sports, Brennan said.

“We have raised these young men now to understand that women deserve equality. And they were the one that advocates for it. And so those are Title IX males in every sense of the word,” Brennan said.

There is more work still ahead.

As Brennan put it, “Today is the greatest day to be a woman in sport, until tomorrow, and then the next day and the next day.”

One of the things Brennan wants to see more of is women coaching women. She also said that while Title IX has had great impact in some areas of the U.S. in the last 50 years, there are places where it can still grow and influence the development of athletes.

“Do a much better job of making sure that everyone is getting the opportunity to play sports, every girl in high schools, whether they be well-off areas in the suburbs or underserved areas, whether that be in rural areas or in urban areas,” Brennan said.

And when people see King’s dress at the Smithsonian, Jentsch said, the museum hopes to convey, first and foremost, that representation is important.

“Entertainment and sports can help everyday people see themselves in the world around them and that our history can help us understand and contextualize current issues and debates around difficult topics like race, gender and identity,” he said. “We also want to convey that our experiences around sports and entertainment can bring us together and participate in these conversations.”