Karen Gray Houston can still remember her first bus ride.

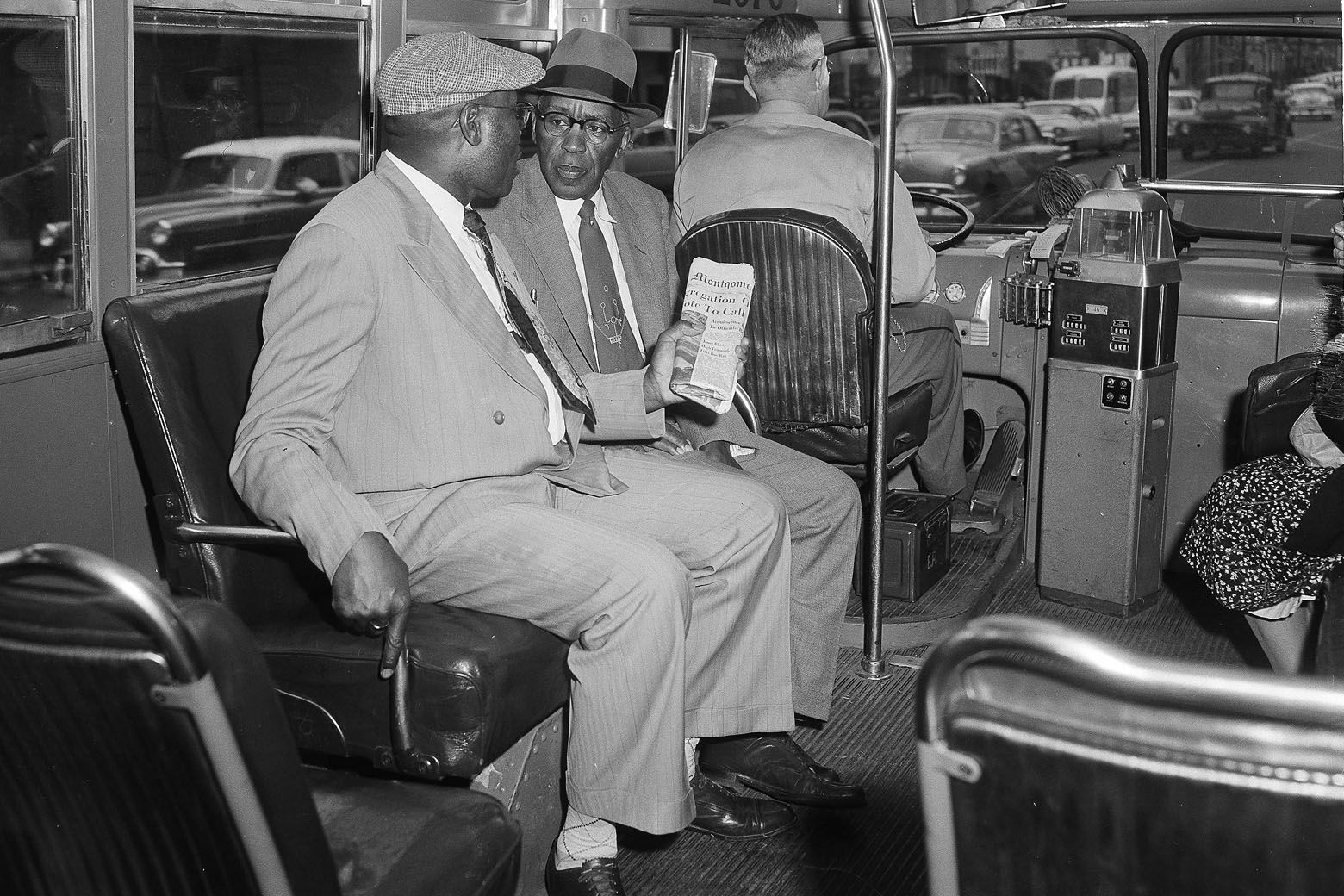

She wasn’t much older than 4, and it was shortly after the end of the landmark Montgomery bus boycott — the exhausting, exhilarating 382 days beginning in December 1955, when thousands of black citizens refused to set foot on the city’s buses in a coordinated, mass effort to break the back of segregation in the heart of the South.

Houston’s family had a car, so they didn’t usually ride the bus. But on that day, there she sat, perched in one of the first rows, alongside her two younger brothers and her mother.

“After the boycott, Mom took us on the bus and sat us in seats in the front of the bus,” Houston recalled, “so we would know what it felt like to be Negroes who did not have to sit in the back.”

The story of the bus boycott is a familiar piece of civil rights lore.

But Houston — a veteran reporter in D.C. who spent 20 years at Fox 5 and, before that, several years as a reporter and anchor here at WTOP — has an uncommon connection to the events that galvanized the civil rights movement.

“For me, this is personal. This is a family story,” Houston said in an interview about her debut memoir, “Daughter of the Boycott: Carrying on a Montgomery Family’s Civil Rights Legacy,” published May 5 by the Chicago Review Press.

Houston’s father, Thomas Gray, was an activist who worked tirelessly during the protest sparked by Rosa Parks’ arrest — he was part of an elaborate carpool operation to help people avoid taking the buses.

And her uncle, Fred Gray, who became known as the “boycott lawyer,” defended Parks and several other women whose mistreatment by city authorities would lead to the Supreme Court case that overturned segregation on the city’s bus lines.

After retiring from her reporting career in spring 2014, Houston spent years researching and writing the book — even temporarily moving back to her birthplace of Montgomery, Alabama — trying to uncover untold stories of ordinary people who kept the movement going, and to finally learn the full story of the heroism in her own family.

“To me, this is a tribute to my father and my uncle for what they did that opened up doors of opportunity for me and for countless other people,” Houston said.

Before the boycott

Houston’s book begins with a little-known event several years before Parks’ famous stand.

In 1950, still a decade and a half before the Voting Rights Act was signed into law, Houston’s father led a public battle against police brutality that culminated in a march of black veterans through downtown Montgomery to the courthouse to register to vote.

The demonstration was sparked by the police killing of Hilliard Brooks, a childhood friend of her father’s and, like Thomas Gray, a World War II veteran.

In August 1950, Brooks was boarding a Montgomery bus.

“Admittedly, Hilliard was a little drunk and disorderly, and the bus driver called over a police officer,” Houston said.

“By then, Hilliard had gotten off the bus, but when the police officer came over, something happened, there was some sort of dispute between the two of them — and even witnesses can’t agree on exactly what happened — but the police officer pulled out his gun and shot Hilliard Brooks, who died later in the hospital.”

The white officer’s bullet also wounded two passengers on the bus. Later, some witnesses disputed the police officer’s account of why he fired on Brooks.

“When my father found out about it, he flew into a rage,” Houston said.

He sent off letters to city officials demanding the officer be prosecuted. Instead, a police review board ended up clearing the officer.

“So my father started a protest,” Houston said.

The protest drew hundreds of demonstrators — mostly other veterans, Houston said.

They were wary of being arrested for loitering, a tactic police used to shut down demonstrations. So they marched with a purpose.

“They went downtown to register to vote,” Houston said. They carried signs reading, “Ballots will stop bullets.”

It was an incredible act of bravery during some of the darkest days of the Jim Crow South.

“That was five years before the boycott, but it set the stage for it,” Houston said.

“I mean, this was about an incident involving somebody trying to get a ride on the bus, and how people were being treated just for taking the daily ride to work.”

Lost in the shuffle of history

Five years later, Rosa Parks’ famous refusal to give up her seat to a white passenger would trigger boycott and, ultimately, jump-start the civil rights movement.

Houston’s uncle, Fred Gray — only the second black lawyer to ever set up practice in Montgomery — defended Parks in court on a charge of disorderly conduct.

Gray had gone to law school up North and came back home with the intention of, in his words, “destroying everything segregated I could find,” Houston writes in the book.

But it was actually one of his earlier cases, involving a young woman named Claudette Colvin, that eventually made its way to the Supreme Court and overturned Alabama’s bus segregation laws.

“My uncle had just rolled out of law school. He was about 23 years old, and this was his first civil rights case,” Houston said.

Colvin was a 15-year-old Montgomery girl who had refused to give up her seat on a bus and was arrested — nine months before Parks.

However, leaders in the burgeoning civil rights movement hesitated to rally around Colvin as their cause célèbre after she became pregnant that summer.

“They didn’t think that a pregnant, unwed mother should be the face of a test case of segregation,” Houston said. “So Rosa Parks got more attention.”

Colvin’s story has only recently emerged from the shadows. In her book, Houston recounts interviewing the reclusive Colvin at her home in New York City, where 60 years later, she has begun “demanding what she sees as her rightful place in history.”

Still, Colvin and the cases of the three other women who made up the landmark case that outlawed segregation on the city’s buses — Aurelia Browder, Susie McDonald and Mary Louise Smith — are not yet household names.

“Those other women have been sort of lost in the shuffle of history,” Houston said.

“People don’t think about them. They think about the narrative about Rosa Parks being tired on the bus and refusing to get up that day.”

Untold stories

Houston said that when she was growing up, her father and uncle rarely discussed their famous civil rights battles. She likened their reticence to that of men who come home from war.

“My uncle and my father hadn’t really conveyed a lot of what they had done as activists and as lawyers, so I had to go and find out some things,” she said.

Houston began working on the book after retirement from Fox 5 in the spring of 2014, after two decades in front of the camera.

She knew memories were fading and many people who lived through the movement’s early days weren’t getting any younger.

“If I wanted to tell the story right, I needed to get to the people as soon as possible,” she said.

Her father — who had followed in his brother’s footsteps, becoming a lawyer and working to challenge housing segregation before becoming an administrative law judge in Alabama — died from cancer in 2011. But not before Houston and one of her younger brothers spent hours interviewing him about his activism — interviews she saved on tape.

Fred Gray is still living, and still practicing law in Montgomery.

He still goes to the office most days, Houston said, and in December, around the time the bus boycott celebrates its 65th anniversary, he’ll celebrate his 90th birthday.

As Houston worked on the book, she decided to temporarily move back to her grandmother’s home in Montgomery to conduct research and interviews — to be closer to the story.

She joined a local civic organization called One Montgomery, where she hoped to make some contacts.

At one of the first meetings she attended, she introduced herself to members of the group. She told them she was working on a book about the boycott and was looking for people to interview.

“Even before the end of the meeting, a woman at my table leaned over and said, ‘You’re going to want to talk to me, because my father was Clyde Sellers'” — the intransigent police commissioner during the bus boycott who did everything he could to prevent integration from happening.

In the book, Houston also recounts the story of a white Methodist minister, Ray Whatley, who was part of an interracial group of ministers who met in the basement of Dr. Martin Luther King’s Dexter Avenue church during the early days of the movement.

He was exiled from his church in Montgomery for preaching about integration, Houston said.

“These are little-known stories,” Houston said. “People don’t know about these people. You will hear some names you’ve never heard before and discover some people who should have gotten more credit than they did for their unsung actions during those turbulent times.”

Taking a deeper dive

As a veteran journalist, Houston knew how to get people to open up — and how to tell a good story.

In a career spanning more than four decades, she covered the Reagan White House for outlets including NBC and ABC Radio and became a familiar figure in local D.C. news — including a seven-year stint as a reporter and anchor at WTOP in the 1980s and 1990s.

But there were still more lessons to be learned.

“Sitting down to write a book is actually, I learned, nothing like reporting the day-to-day news,” she said. “You’ve got to take a deeper dive.”

Overall, Houston said she hopes her book “fills in some blanks” in the famous story of the Montgomery bus boycott.

“I think the biggest takeaway is that extraordinary results can come from the efforts of ordinary people,” Houston said.

“I mean, there were 40,000 black people who lived in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955. And for the most part, none of them rode the buses for 382 days. A lot of planning went on behind the scenes that people don’t know about.”

Karen Gray Houston is hosting several book discussions via Zoom to discuss her memoir, including one May 14 at 7 p.m., where she will be interviewed by former WUSA anchor Derek McGinty for a Zoom event hosted by the Metropolitan AME Church in D.C. Details will be available via Houston’s Twitter account.