WASHINGTON — Last Saturday, yellow tape marked off rectangles in a small area on the National Mall, south of the Reflecting Pool between the Lincoln Memorial and the World War II Memorial. A small hand-lettered flag marked the inside of each space.

Park ranger Susan Philpott, of the National Park Service, said the scene was a “symbolic re-creation” of Resurrection City — the tent city that was home to the Poor People’s Campaign, which she called “the biggest protest on the Mall that nobody’s ever heard of.”

The Poor People’s Campaign was Dr. Martin Luther King’s last dream, and it came into being 50 years ago this week. While his “I Have a Dream” speech of 1963, and the Selma March of 1965, are burned into the country’s memory, mention the Poor People’s Campaign and you’ll mostly get blank looks or dim attempts at remembrance.

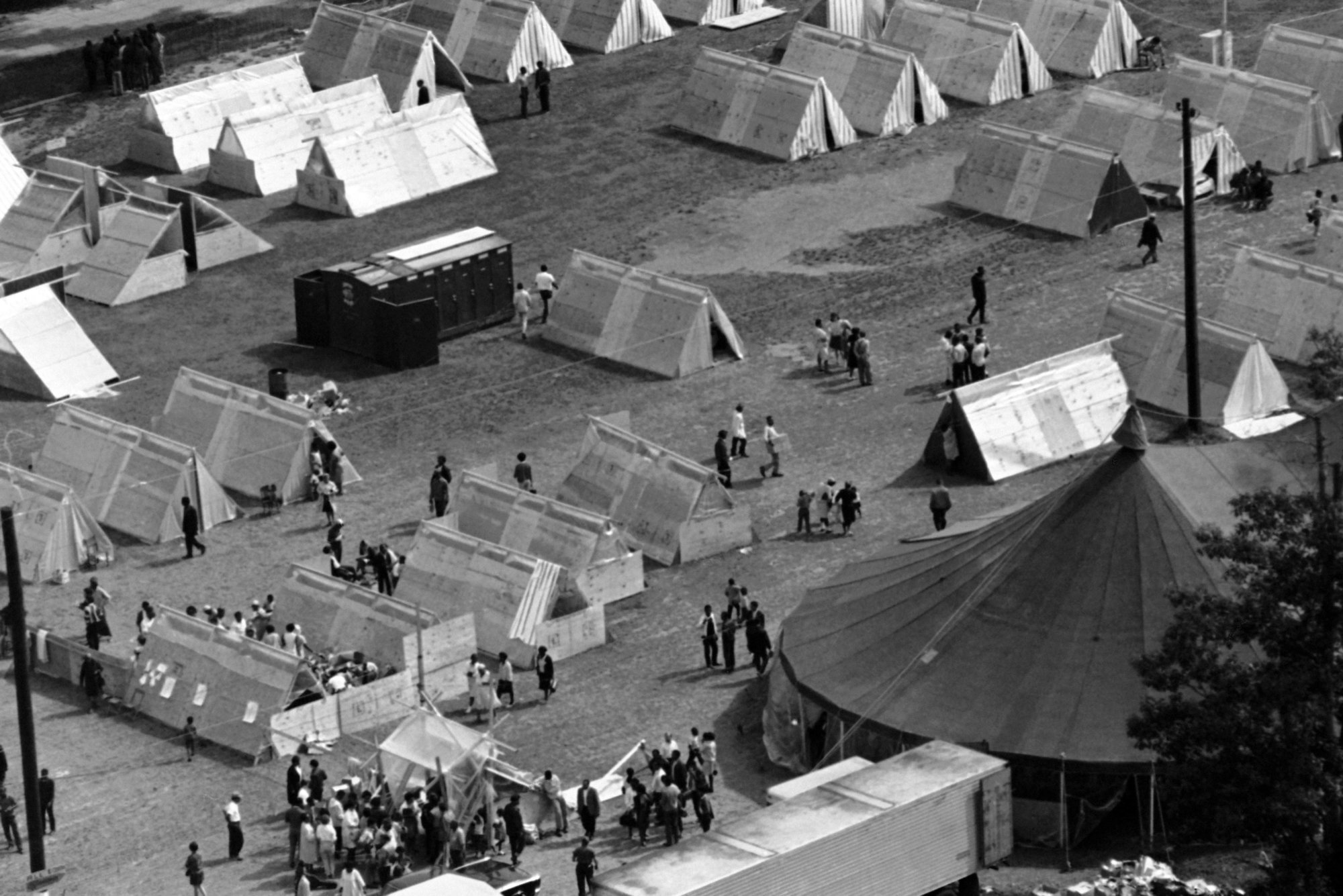

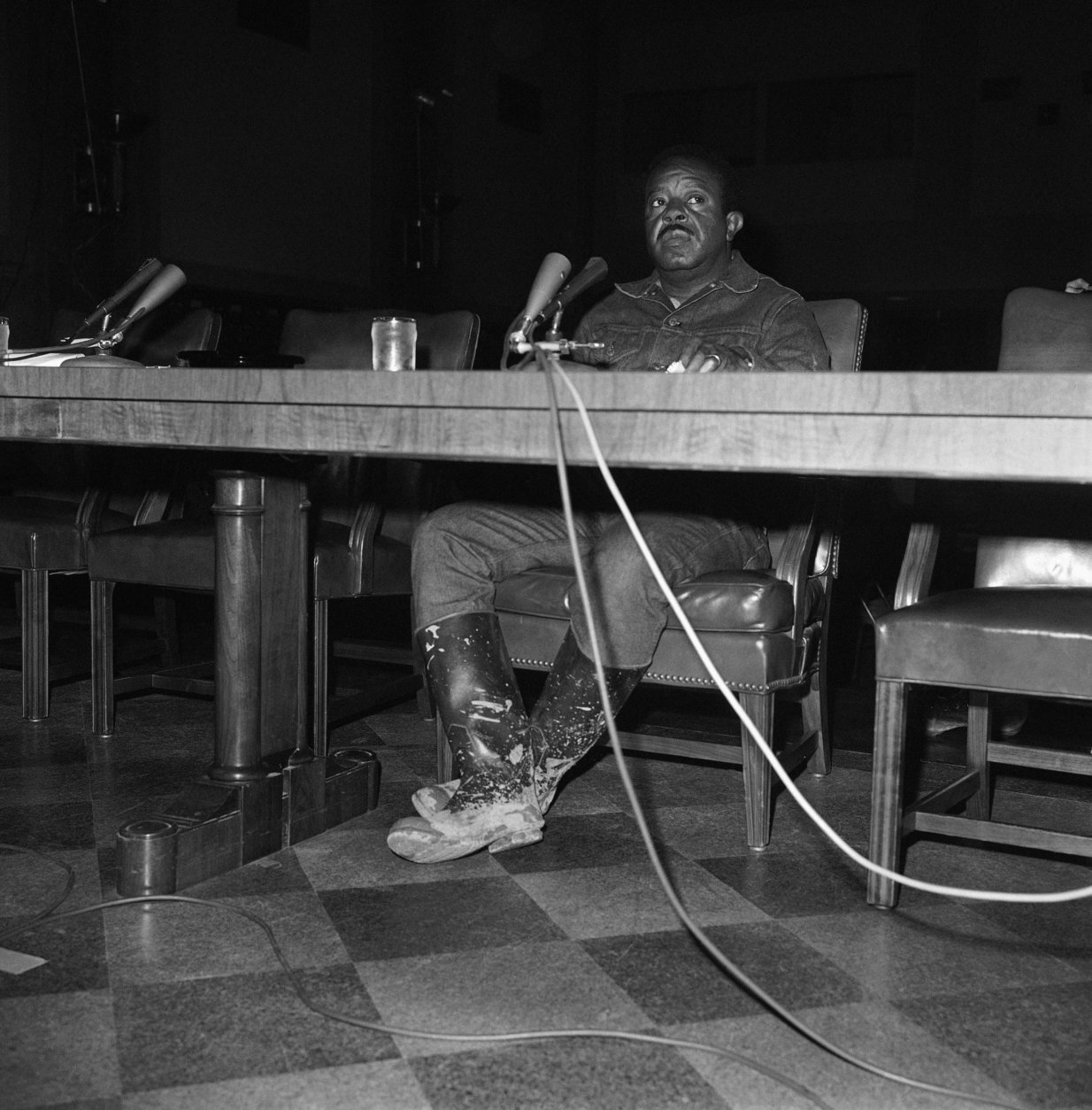

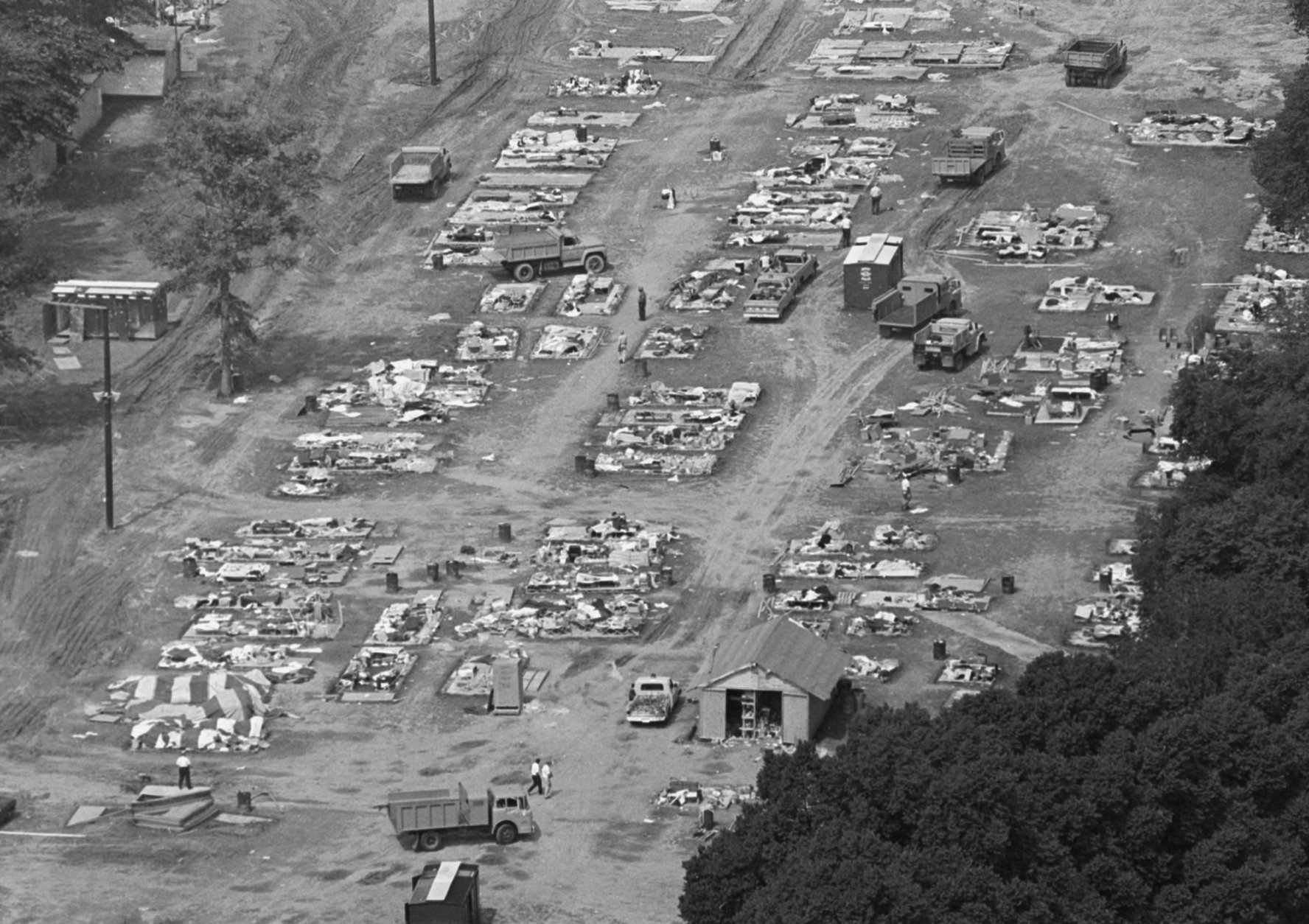

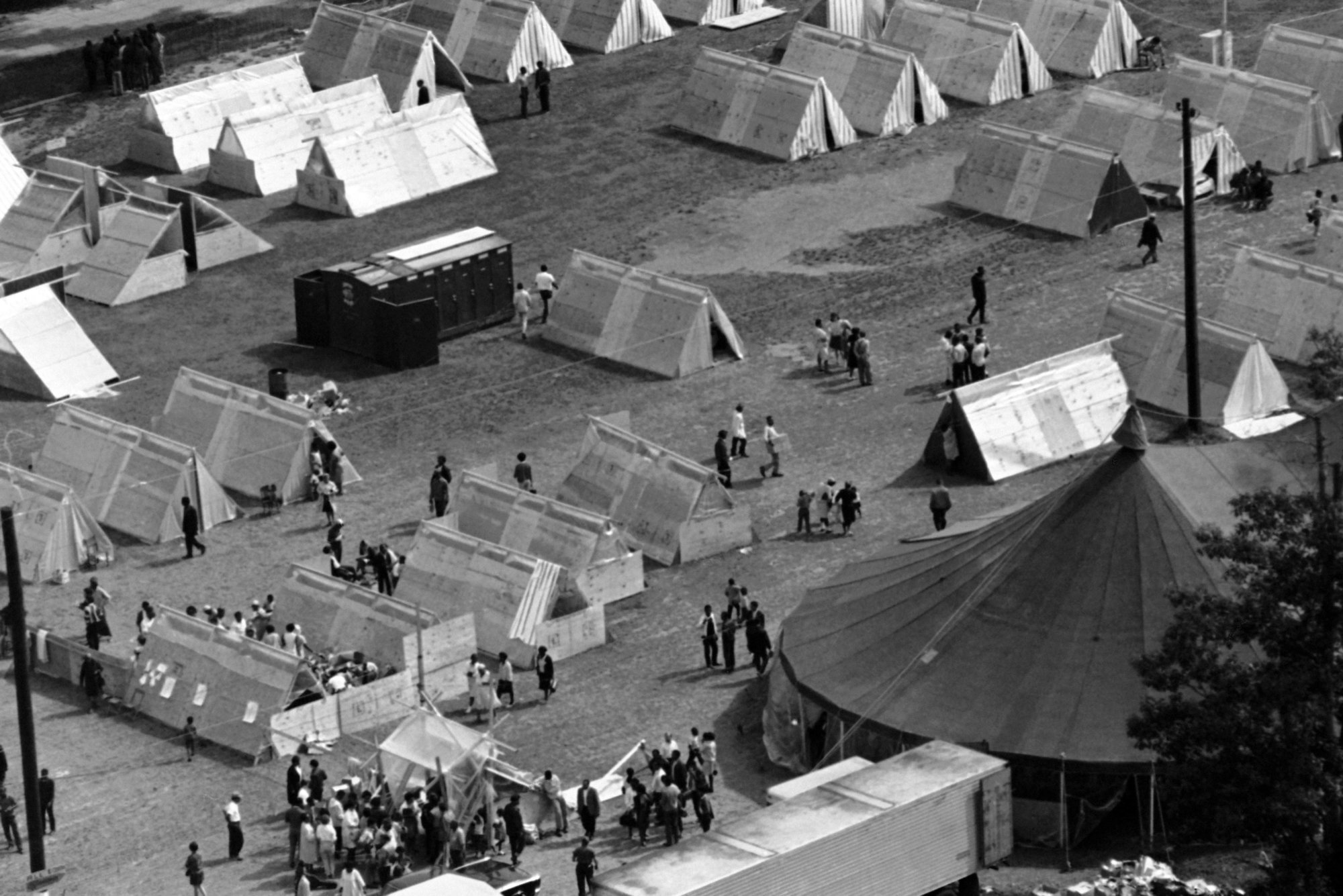

From May 15 to June 24, 1968, an encampment of poor people and anti-poverty activists from all over the country occupied, and lived on, the National Mall just south of the Reflecting Pool between the Lincoln Memorial and what is now the World War II Memorial. They lived in a town’s worth of hastily built tents to provide a living example of protests, solidarity and visibility. The activists were called the Poor People’s Campaign; the encampment was known as Resurrection City.

Visitors passing by on the sunny afternoon were offered packages of tape and flags, as well as instructions on how to mark off the area that each of Resurrection City’s tents occupied. They could also see a visual presentation on the encampment, and hear the history from Philpott and other rangers.

“We feel like people have connected,” ranger Jennifer Epstein said, but she added that no one — outside of the occasional longtime D.C. resident — knew anything about the campaign.

“In many ways,” said Aaron Bryant, of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, “the Poor People’s Campaign gets lost in history. It’s not being talked about as much in the popular culture.”

But for 41 days, Resurrection City was its own town. It had a barber shop, a city hall, a mess tent, a day care — even its own ZIP code. At its height, about 2,700 people lived in the wood-and-canvas tents.

“They came from everywhere,” historian Gordon Mantler told WTOP: Caravans organized by the SCLC and religious, labor and community groups came from the West Coast, the Northwest, the Southeast, New England — all over the country.

While the encampment doesn’t get as much attention as other iconic protests from the late 1960s, a series of interviews with participants and historians shows that Resurrection City’s effects influenced activists for more than a generation, including those who formed Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter and 2017’s Women’s March — whether they all realize it or not.

A broad agenda

In 1967, lawyer and activist Marian Wright was testifying to Congress about the poverty people were facing in her native Mississippi, and she encouraged lawmakers to come down and see the conditions people were living in for themselves. On the trip, Sen. Robert F. Kennedy suggested that a contingent of poor people come to D.C. and bring the same message to the lawmakers’ doorsteps.

King and other activists had the same idea. In January 1968, King announced in a speech, “We are tired of being on the bottom. … We are going to Washington, D.C., the seat of our government, to engage in direct action for days and days, weeks and weeks, and months and months if necessary, in order to say to this nation that you must provide us with jobs or income.”

He didn’t live to see the Poor People’s Campaign take shape; he was killed April 4 of that year. Resurrection City was delayed, but it went on, with a new group at the head of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference and a wider agenda than anything King had ever attempted before.

By that point, King had been focusing his activism on more than voting and civil rights, to include the thornier, and more pervasive, problem of economic inequality — and not just among black people.

Where King’s earlier civil rights campaigns were black-centered, the Poor People’s Campaign sought to form a coalition among black, Native American, Latino and white people, and to forge a group consciousness on a systemic, national problem.

The Poor People’s Campaign had five core demands:

- a meaningful job at the living wage for every employable citizen;

- a secure and adequate income for all who cannot find jobs or for whom employment is inappropriate;

- access to land as a means to income and livelihood;

- access to capital as a means of full participation in the economic life of America; and

- recognition by law of the right of people affected by government programs to play a truly significant role in determining how they are designed and carried out.

These general goals were fleshed out in 49 pages of specific recommendations targeted at the relevant Cabinet secretaries.

This was an attempt at a fundamental change in attitude toward poverty, but that carried risks: In his 1969 book “Uncertain Resurrection,” Chuck Fager, a former staffer at the SCLC, wrote, “This meant [King] could not any longer center his appeal on values all Americans were, on paper at least, committed to support.” According to Fager, King strategist James Bevel was even more blunt: “There’s nothing unconstitutional about children starving to death.”

A city rises

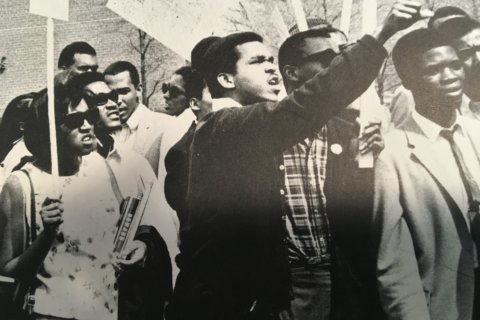

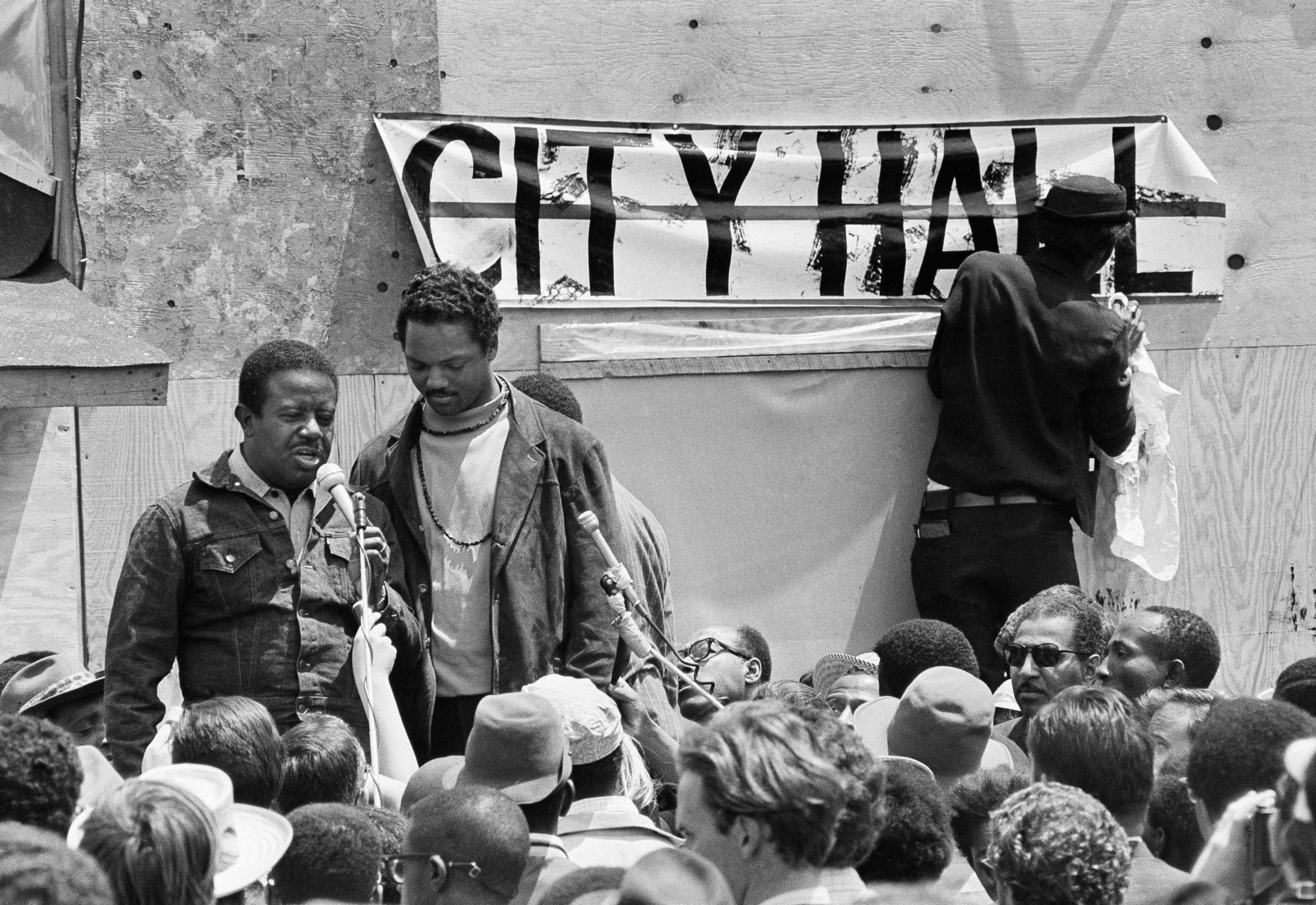

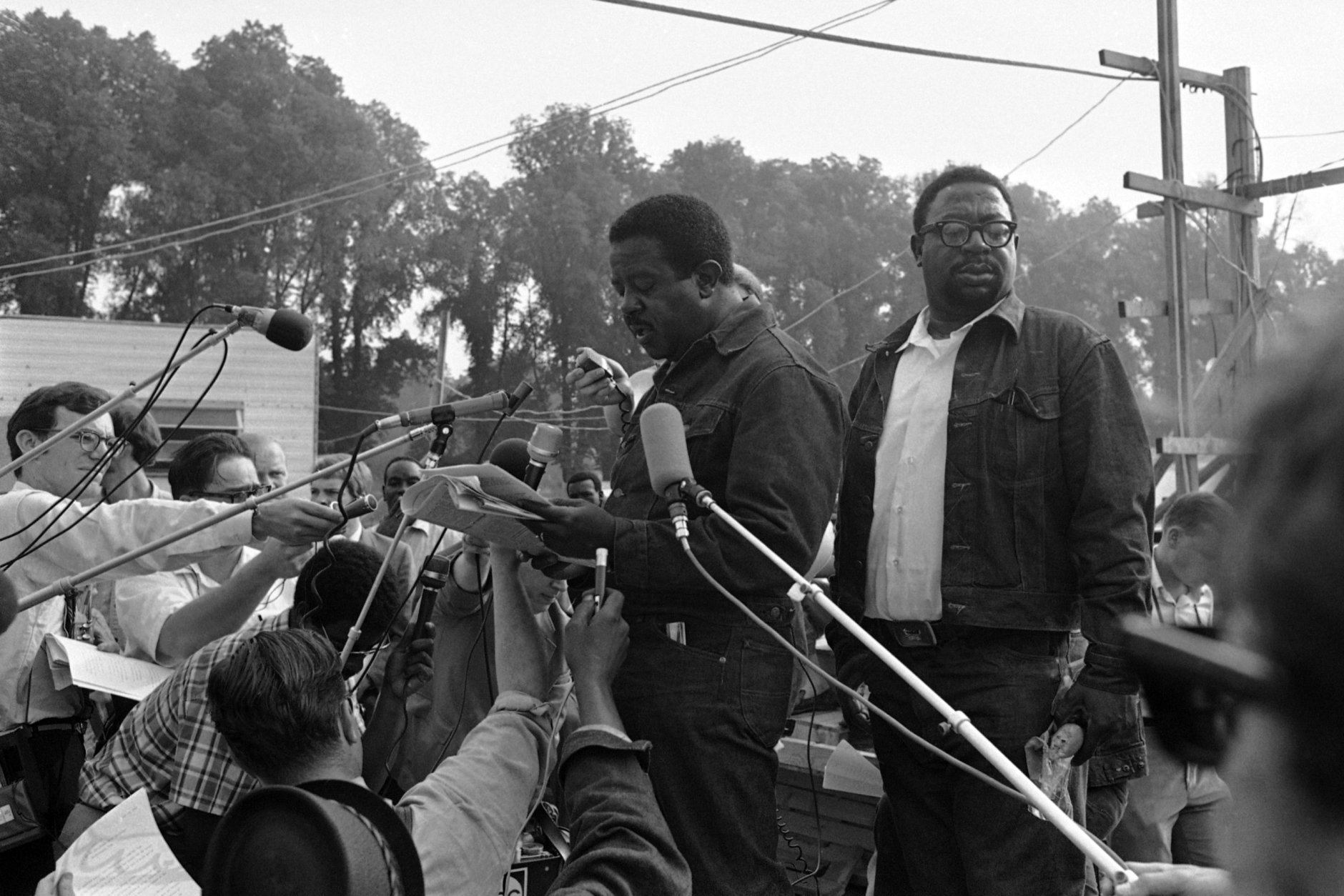

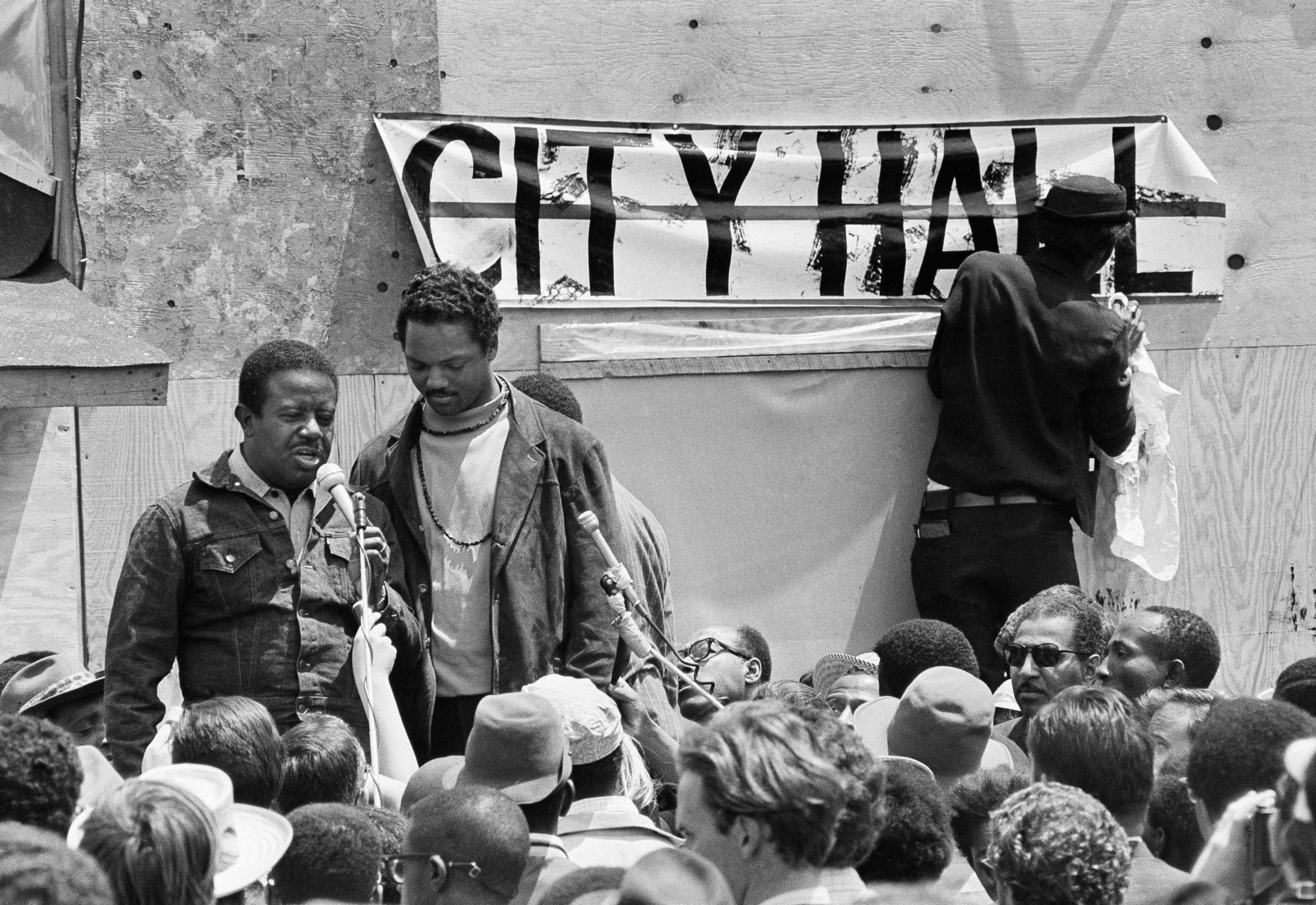

Ralph Abernathy, who succeeded King as the leader of the SCLC, drove the first nail into one of the tents on May 13, at the tail end of a Mother’s Day march in Washington. The Rev. Jesse Jackson served as manager of Resurrection City.

The tents were a marvel of quick, simple, practical design. University of Maryland architect John Wiebenson designed them not only for sturdiness but also for ease of construction, knowing that unskilled volunteer labor would be doing most of the work. He tweaked the design to see “how long it would take to build a tent, how many people were needed to build a tent and how fewer people can build a tent in less time,” Bryant said.

Laura Jones, who came to Resurrection City as a 19-year-old, said the agenda was somewhat dizzying: “There were issues I wasn’t even aware of,” including Native rights. “There were so many issues and so many different groups,” said Jones, who is white, that “there wasn’t even a clear consensus on what the demands were.”

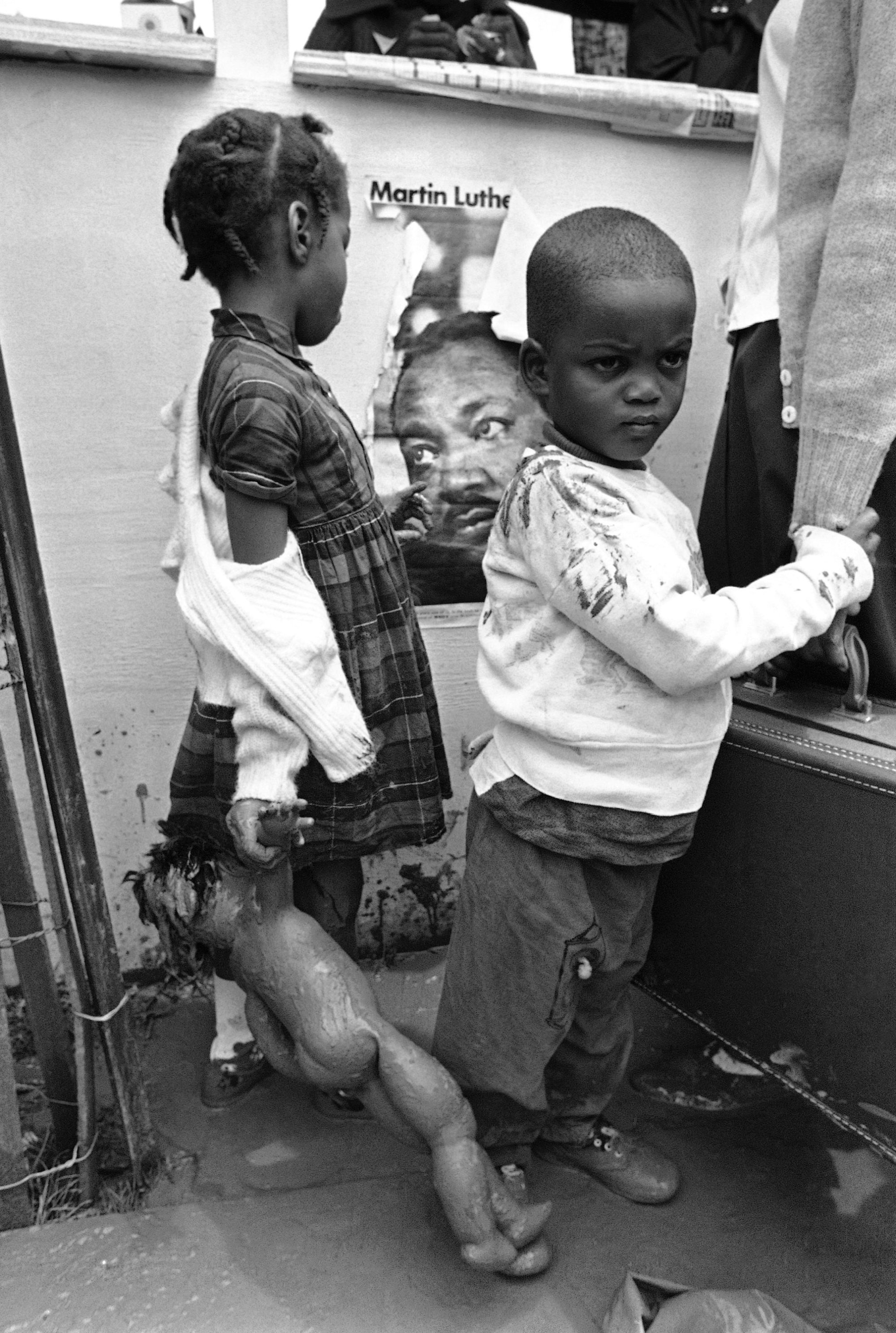

It rained more than half the days Resurrection City was up. In late May, a storm knocked down the dining hall and forced the evacuation of about 1,000 people; on June 12 and 13, around 2 inches of rain fell. “It was mud and rain and very uncomfortable,” Jones said.

The newspaper accounts of the time, especially in the Washington Evening Star, as well as Jones’ memories, paint a picture of an occasionally miserable, occasionally dangerous place. The papers contained virtually daily accounts of violence perpetrated by Resurrection City residents on passing tourists, media members and, occasionally, one another. Jones said now that “I don’t think [reports of violence were] overblown. I did not always feel safe.”

Three men tried to steal her camera one night “and scared me considerably. There was violence.” Some of the people behind the violence were rounded up by the organizers and sent back to their hometowns, “but that fear was certainly there.”

Still, she’s glad she went. “I realized that I had more skills than I thought I had, and more ability to not only document things I believe in, but use my voice and talk about them.” She spent most of the time in the encampment talking and listening to activists from all over, and through those conversations, “I started realizing what I thought, and what I wanted to say.”

A chance to speak

After King’s death, there was an emphasis on reaching out and helping to heal the wounds of the black community, especially in D.C., after the rioting that followed his assassination.

“At the time,” said Noel Lopez, a cultural anthropologist who works for the National Park Service, “there was an openness to coming up with different approaches at racial reconciliation.” (One of those approaches was the Summer in the Parks series, which brought activities and arts to D.C.’s parks and, Lopez said, helped create a generation of go-go and rock musicians in the District.)

It’s hard to imagine an open-ended, residential project like Resurrection City getting a permit nowadays. The original application for 36 days was approved, Lopez said, but “there was no formal idea of what [it] was going to look like, because no one had done that before.”

That said, President Johnson and his administration were against the idea, Mantler said: Even though Johnson had seen his share of poverty growing up in the Hill Country in Texas, “he thought it was a terrible idea, and he was concerned about violence breaking out.”

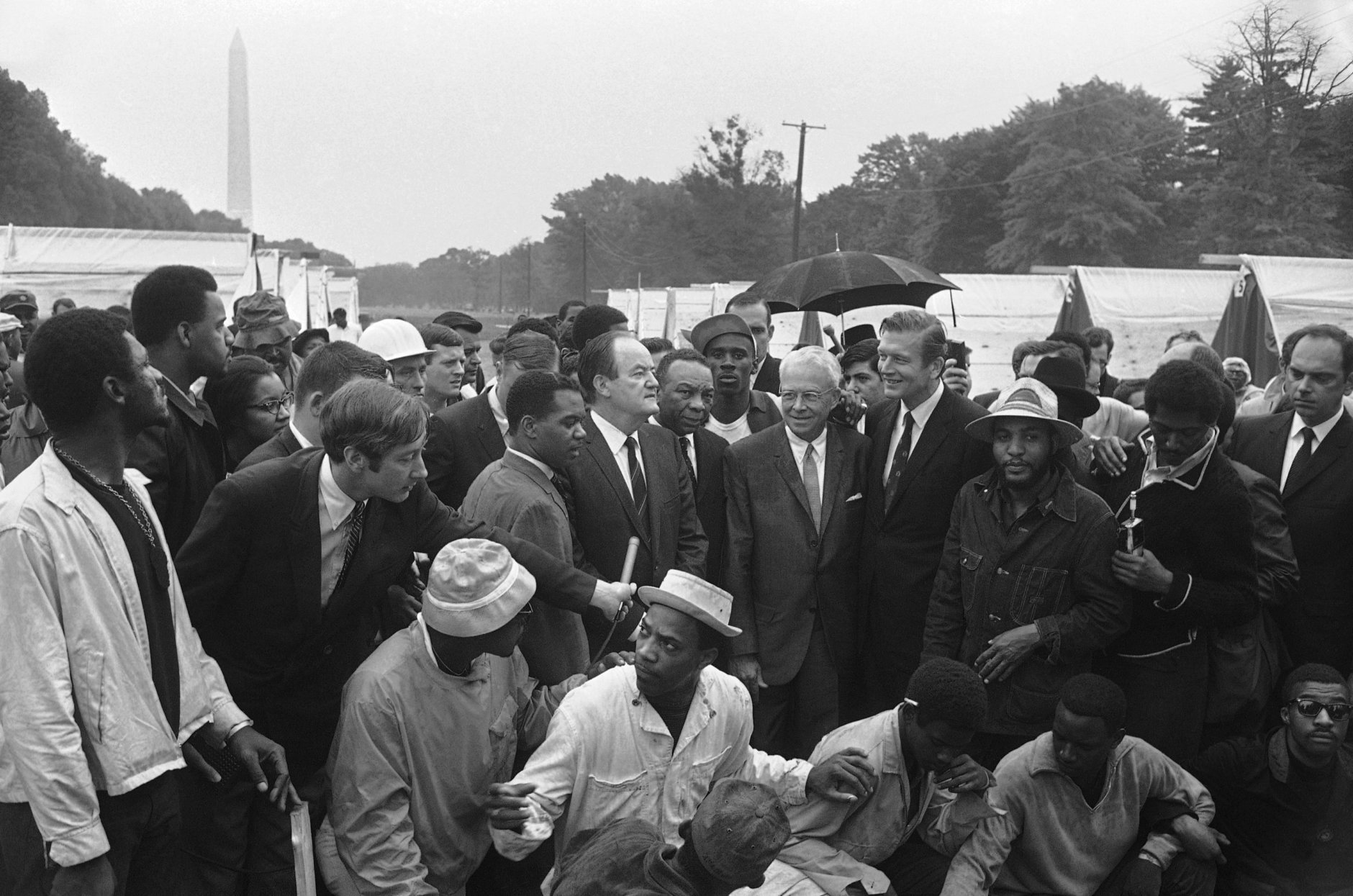

While the encampment served as a home base for protests and demonstrations that fanned out into the city, including at the Supreme Court and the Department of Agriculture, senators and congressmen visited Resurrection City regularly; so did Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who predicted during his visit that it was “going to produce results … I think we can learn a lot here.”

That attitude wasn’t universal: Sen. John McClellan, a Democrat from Arkansas, called the march “a premeditated act of contempt for and rebellion against the sovereignty of government.” Sen. Russell Long, a Democrat from Louisiana, said, “When that bunch of marchers comes here, they can just burn the whole place down, and we can move the capital to some place where they enforce the law.”

May 29 was one of the most incendiary days of the Poor People’s Campaign, when a demonstration at the Supreme Court resulted in dozens of arrests as protesters were accused of breaking windows. A contingent of mostly Latino protesters was attacked by the D.C. police as they headed back to the Hawthorne School, where many protesters also stayed.

The crowning moment of Resurrection City came June 19 — the unofficial African-American holiday Juneteenth — when up to 150,000 people met on the National Mall for Solidarity Day, which included speeches by Coretta Scott King; King’s successor, Abernathy; and a passel of activists from all over.

The original permit for Resurrection City had expired, and the extension had only a few days left. Abernathy, however, told the crowd, “I don’t care whether the Department of Interior gives us a permit to stay on in Resurrection City. I received my permit a long time ago … from God Almighty.”

The end

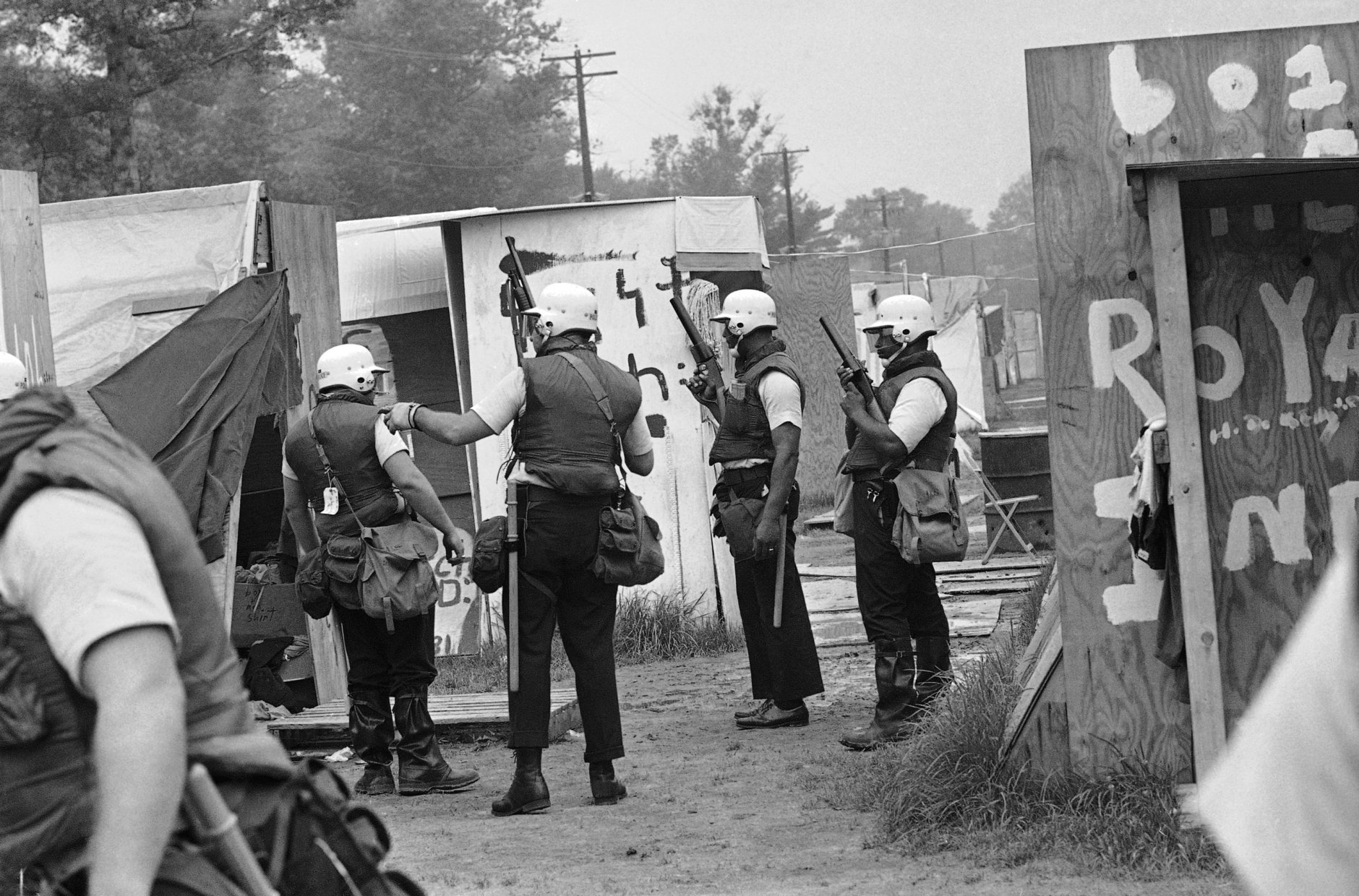

But on June 24, about 16 hours after the final extension of the permit expired, Resurrection City was broken up by about 1,000 police officers with tear gas. By this time, the population had shrunk from 2,700 to about 500. Abernathy and some of the other leaders were arrested in a protest near the Capitol.

Even some of the organizers thought it was time to wrap it up. Organizer Hosea Williams said: “I want to thank the government for getting us out of it. … [Now] we can focus on the real problems with Congress for instance, instead of wasting half our energy trying to keep kids from throwing rocks.”

The arrest of Abernathy and other leaders of the march was planned in advance with the authorities, said D.C. historian Sam Walker, author of “Most of 14th Street is Gone: The Washington, DC Riots of 1968.” But not everyone got wind of the plan, and a repeat of the rioting that plagued the District in the wake of King’s assassination loomed again, Walker said.

A contingent of the Resurrection City occupants had nowhere else to go. Many weren’t from D.C., so they literally didn’t know where they were. They wound up at 14th and U streets in Northwest, known as the center of the District’s black community — and the epicenter of the previous month’s violence.

“And they were annoyed, at least, that their leaders had been arrested,” Walker said. “So there were some demonstrations; there was some breaking of windows in stores.”

The previous month’s unrest was set off by an unexpected incident; this situation came from a planned series of events, at a time when the authorities were already on edge. A large contingent of police and National Guard troops were quickly moved in, Walker said: “They fired off lots of tear-gas grenades, and that quickly broke up the protests.”

The journalist I.F. Stone wrote at the time: “Resurrection City is supposed to have been a mess. I found it inspiring. It reminded me of the Jewish displaced persons’ camps I visited in Germany after the war. There was the same squalor and the same bad smells, but also the same hope and the same will to rebuild from the ashes of adversity. To organize the hopeless, to give them fresh spirit, to see them marching was truly resurrection.”

What was accomplished?

Bryant is walking through the “City of Hope” exhibit, which he curated and is housed at the Smithsonian Museum of American History. The walls include pictures and artifacts from the six-week Resurrection City demonstration — even a room with a looped recording of the sound of rain falling on visitors’ heads.

The Resurrection City encampment can be credited with a few immediate changes, mostly regarding food stamps and nutrition programs, but it was never going to capture the public’s imagination as the 1963 March on Washington did, Bryant said.

That’s for several reasons: So much of the country, and so many of the organizers, were in mourning for King; the campaign continued for six weeks, without the kind of sound bite that King might have provided, and it was less an appeal to the conscience of the country than an appeal to the slow, grinding process of Congress.

Mantler said it helped forge a generation of activists through the 1970s and ‘80s by bringing together people who had more in common than they might have otherwise realized. “There were these opportunities for building relationships and individual conversations that are often lost when we think of social movements,” he said.

“We look at the big rallies and marches and we think, ‘Well, that changed the policy.’ But what’s most important … [is] that folks meet other people, who have a different background than they do but have come to some similar conclusions, and are able to share ideas and stories and experiences with each other that they’re able to take home, wherever home is.”

Tim Wright, an educator who gives walking tours of D.C., added the Resurrection City site to his repertoire after seeing the exhibit, saying that the Poor People’s Campaign provides an object lesson in the unromantic work of getting things done. The March on Washington, King’s assassination, even the rioting in D.C. that came afterward, take up “a lot of educational space,” he said. “But, to me, what’s most important is, what happened after the assassination? What is the legacy of King? And I wanted to shine a light on that.”

A modern-day Poor People’s Campaign is being held May 14 through June 23 — this time, the end date has been set on purpose — in locations all over the country, focusing on issues such as income inequality, criminal justice, military spending, voting rights and more.

Bryant said that modern-day protest movements such as Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter take a lesson from the original Poor People’s Campaign whether they know it or not — the importance of what Wright calls “taking up space.”

It’s an old-style protest technique, and Bryant fears current protesters don’t grasp its importance. “I think activism and mobilization is extremely different now, particularly with social media. Social media helps people to mobilize more quickly, but it can also hinder perhaps, because you can be an activist from the comfort of your living room. With a movement like this, you have to actually be out on the ground.”

The current groups, he said, have done “a really good job of mobilizing … but then, without some sort of other organization to keep the conversation going, you have to wonder what are the next steps.”

By working face-to-face like the Resurrection City movement did, Bryant said: “You share a culture, and then you sort of become part of the same culture. … [And then] you have a stronger commitment to one another.”

Laura Jones said that mainly what she remembered doing was listening and learning. “I spent quite a bit of time just listening to people’s stories and talking to people. … Some of the people who were there had never been out of their counties, never mind in the big city of Washington, D.C., in a shack behind the White House.”

Most accounts of Resurrection City, she said, paint it “as if it were a complete failure. And there were some things about it that failed. But the fact that it survived for six weeks, and there were literally thousands of people who were involved … even the longevity of the attempt to draw attention to the concerns that people had is a remarkable thing.”