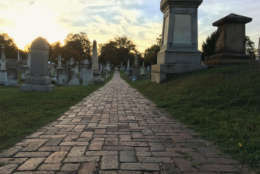

WASHINGTON — Walk around downtown D.C. and throw a stone and you’re likely to hit a historic landmark. But outside the National Mall’s well-traveled paths and its famous monuments and museums, you’ll find another surprising source of art, architecture and history: D.C.’s centuries-old cemeteries.

“I think that cemeteries are forgotten about for their beautiful works of art as well as their beautiful landscapes and just their pastoral, peaceful qualities,” said Anne Brockett, an architectural historian in the D.C. Office of Historic Preservation, who researches the history of D.C. burial grounds.

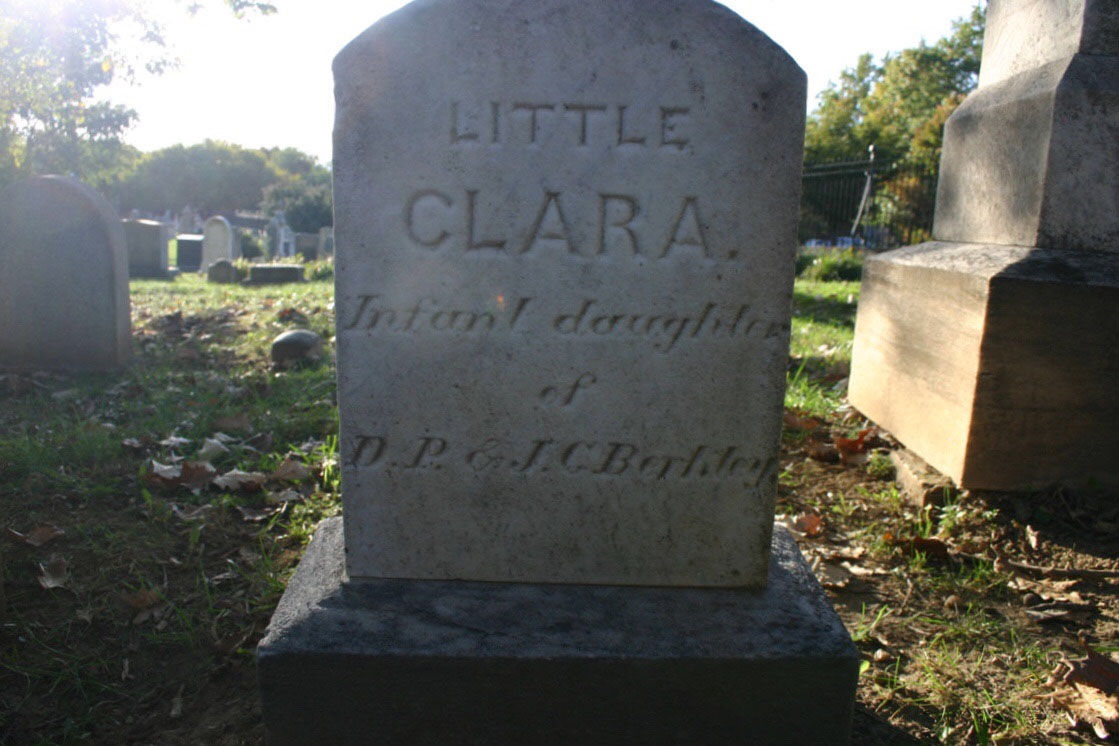

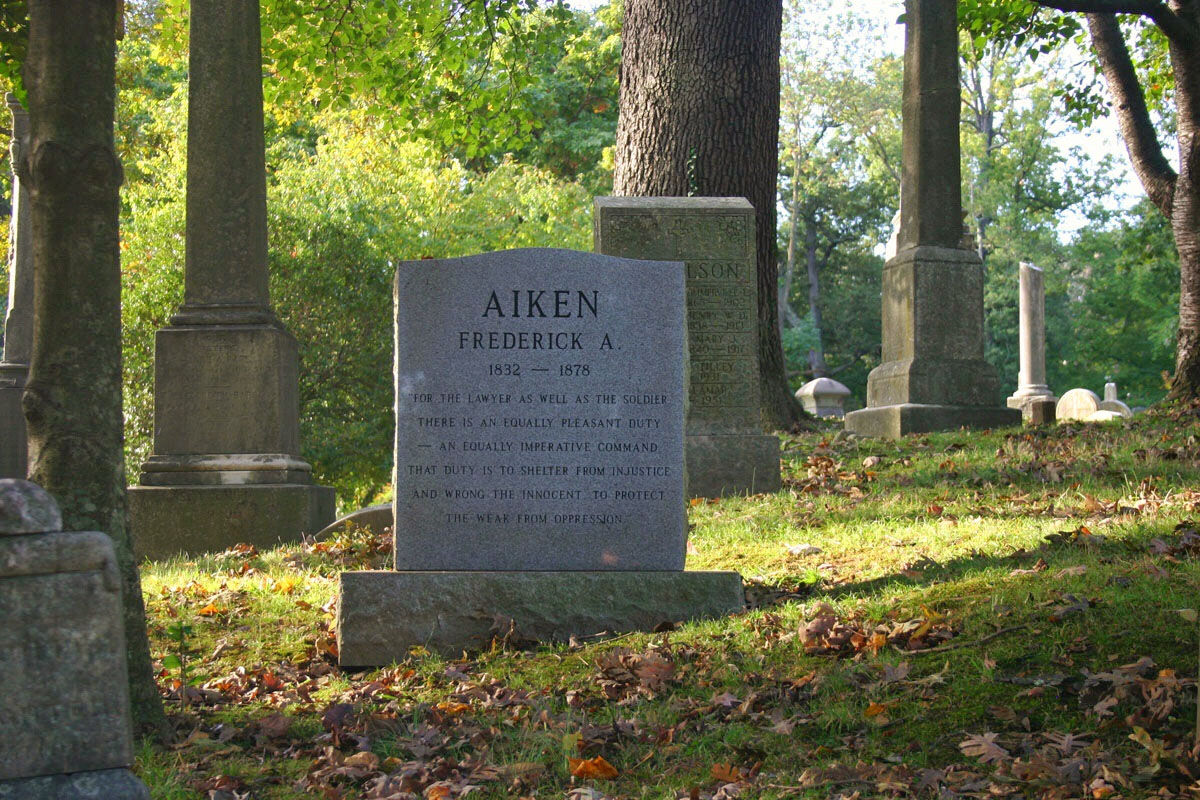

There are about two dozen cemeteries still standing in D.C. — both active and historic — ranging from relatively small plots of land to expanses of meticulously manicured greensward. And the grave markings that dot them range from modest headstones engraved with simple messages to magisterial monuments designed by world-famous architects and sculptors.

Still, despite the wealth of funerary artifacts on display, the full history of D.C. cemeteries may be largely hidden.

Back before D.C. was established, and the area was essentially pioneer territory, burials were held in churchyards or in family plots.

Landscaped lawns and stately rows of marble headstones these were not.

They were overcrowded, unorganized, sometimes unsightly and believed to be unsanitary, Brockett said. By the middle of the 19th century, space was at a premium — bodies in graveyards were literally piling up on top of each other. So, in 1852, Congress passed a law forbidding new burial grounds within the boundaries of the original Federal City.

With the passage of the new law and the creation of new public cemeteries on the city’s outskirts, thousands of graves and grave sites were dug up and moved — a process that continued well into the 20th century to make way for expanding development.

All told, more than 100 family cemeteries and small burial plots that were once recorded in the District have been essentially “lost to time,” according to the historic preservation office.

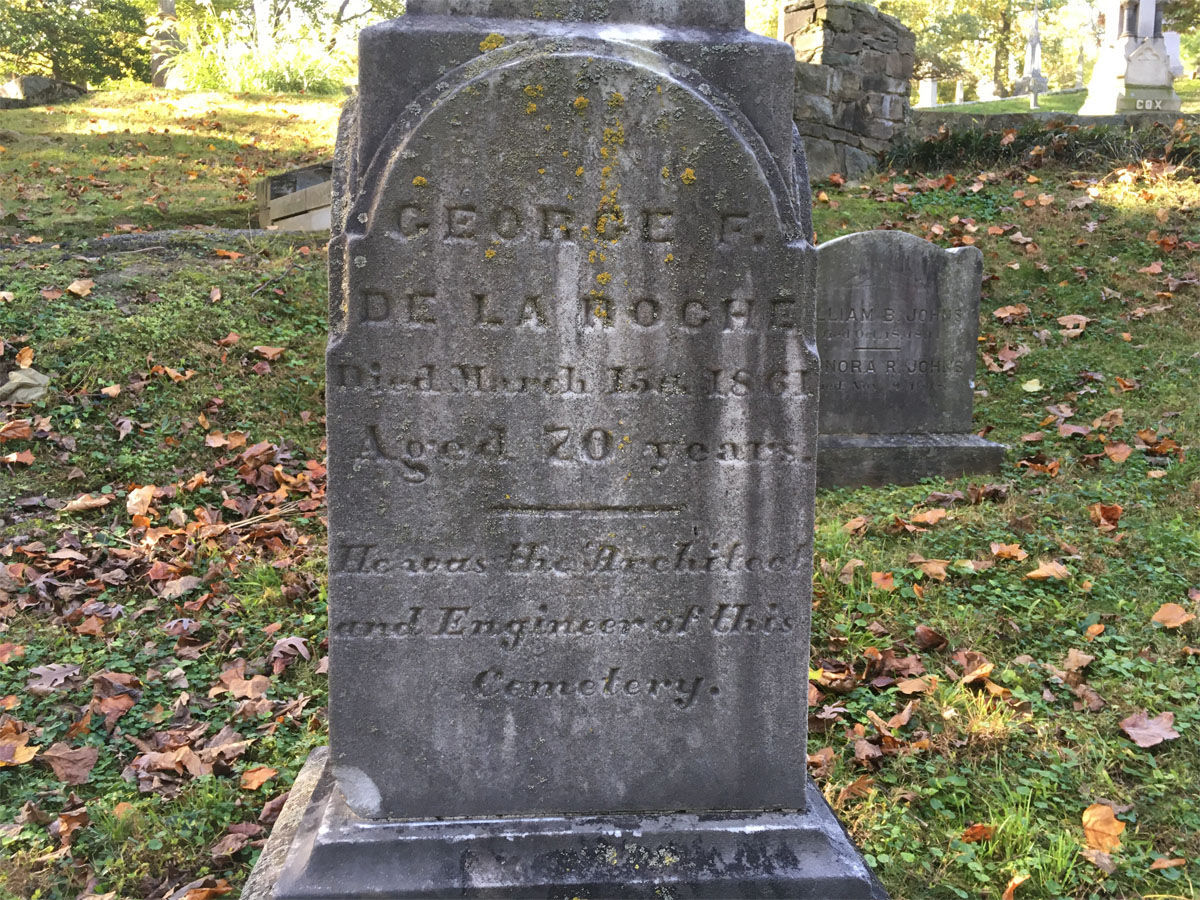

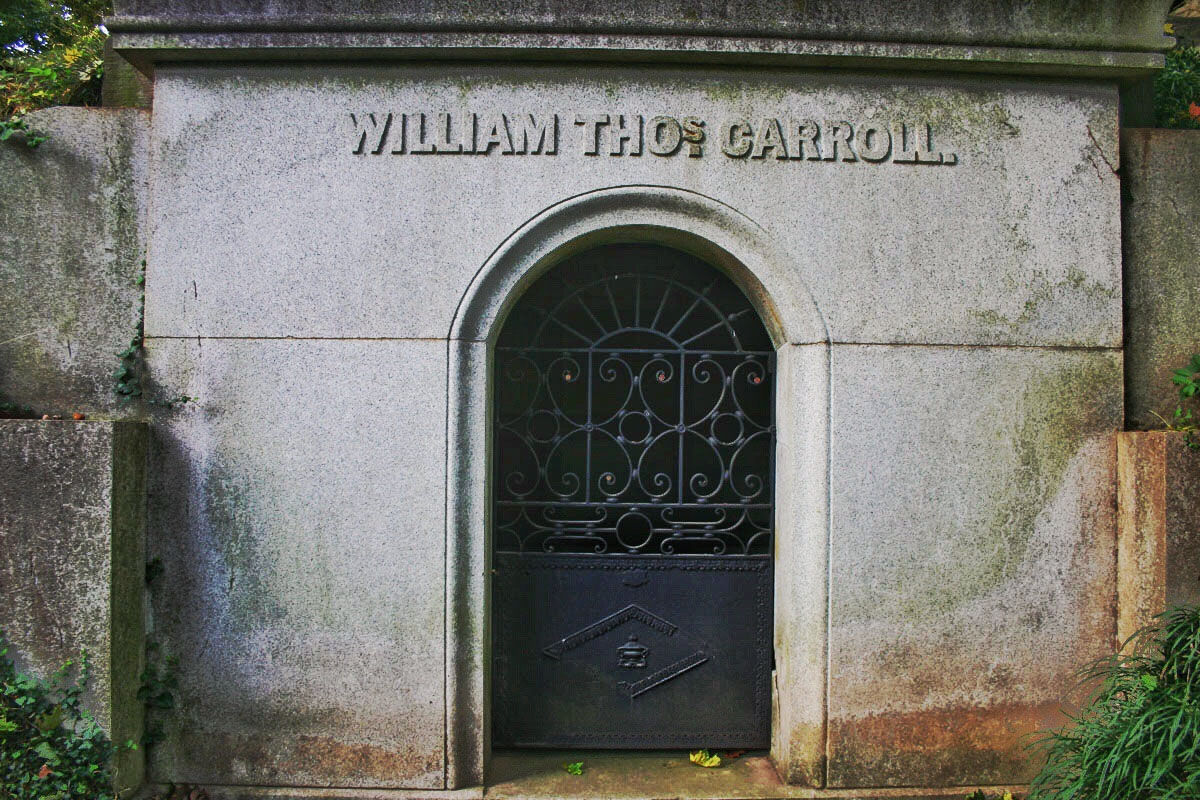

The legislation cracking down on D.C. burials also coincided with a movement to re-imagine cemeteries as a beautiful urban parks. The so-called “garden cemetery” movement has its Washington exemplar in Georgetown’s Oak Hill Cemetery. Set on a hill overlooking Rock Creek and rolling over 22 acres, the cemetery features meticulously designed terraces and winding paths.

Oak Hill is rife with Civil War history. A grief-stricken Abraham Lincoln frequently visited the cemetery as the war raged on to visit the grave of his 11-year-old son, Willie who was temporarily interred in a mausoleum there after dying of Typhoid fever in 1862.

“Lincoln would come here and open the casket and hold the body of 11-year-old Willie in his arms,” said George Hill, president of the Oak Hill Cemetery. “Willie had been embalmed, so it’s not quite as gruesome as you might think. But I think that symbolizes the way people felt about the dead. They were unwilling to give up and let the dead go quietly.”

Some cemeteries rich in history have gone unrecognized and even neglected.

At the Mount Zion/Female Union Band Society Cemetery, which sits on three acres of land tucked away behind a row of Georgetown townhomes, many of the grave stones are broken and jagged.

The cemetery began as a churchyard burial ground for Mount Zion, the oldest African American congregation in D.C. Later, the Female Union Band Society, a cooperative benevolent society of free black women, many of them former slaves, pooled their money together to purchase nearby land to serve as a burial ground for their members.

The cemetery’s pre-burial vault — a small brick structure built into the side of a steep hill on the cemetery’s northern edge — has long been reputed to have been a way station on the Underground Railroad.

But the cemetery fell into disrepair after the last interment in 1950. A halted preservation effort in the 1970s beautified some of the landscape but left grave markers piled up in haphazard rows. There are now new efforts underway to restore the historic cemetery.

Maintaining historic cemeteries that no longer support active burials — and, consequently, for which there is no source of income — is often a struggle, Brockett said.

Weather and erosion take their toll, causing graves to sink. Rain washes out landscaped hillsides, making the ground unsteady. And falling tree branches can damage historic markers.

“So it’s an ongoing battle with Mother Nature to try and keep cemeteries looking cared for,” she said.