EDITOR’S NOTE: In the fourth story in WTOP’s series “Hooked on Heroin: Deadlier than ever,” Jamie Forzato examines why states are putting renewed attention on a life-saving drug.

FAIRFAX, Va. — If Ginny Lovitt had had access to naloxone when her brother overdosed, she might have been able to save his life.

“I was the one who came home and found my brother the day he overdosed and died. At that time, naloxone wasn’t available to the public, so there was nothing I could do about it but call 911 and wait,” the Herndon native said. “I know what it’s like to be in a situation where you need naloxone and [don’t] have it.”

As the heroin and opioid epidemic reaches unprecedented levels in our region, Maryland and Virginia have taken steps to increase public access to naloxone, an opioid reversal drug.

Last November, after declaring a public health emergency, Virginia’s health commissioner issued a standing order for naloxone. Now, any Virginian can walk into a pharmacy and ask for naloxone without a prescription, at a cost of about $120.

The open access to the drug comes at a time when the death toll from fatal overdoses in Virginia has climbed to historic levels. When all of the opioid fatalities are calculated for 2016, officials believe more than 1,000 lives will have been lost — a record for the state.

Recovery advocates applauded Virginia’s decision, but Lovitt said additional steps are needed to curb this crisis to be on par with Maryland, which allows state-certified trainers, like her, to dispense naloxone during their free training seminars instead of requiring people to take a trip to the pharmacy.

As the Virginia and Maryland legislative sessions begin, several bills aimed at expanding access to naloxone will be on the table. And Lovitt has made it her personal mission to teach anyone who will listen about the drug that can bring someone back from the brink of death.

Regret turns into a calling

Christopher Atwood struggled with heroin abuse as a teenager and a young adult. His family enrolled him in several expensive private treatment programs all over the country. Eventually, he finished each one and was released back home.

“Every day that I came home I wondered if I would find him overdosed. And one day I did,” Lovitt said.

On the morning of Feb. 22, 2013, her worst nightmare became reality.

“I walked in and he was lying on his bed and his arm was a funny color … I turned him over and he had been choking … I tried to do CPR but it was too late,” Lovitt said. Christopher was 21.

Lovitt still harbors some regret.

“He was my only brother and I loved him more than life itself. How could I not help him? How could I not cure him? How could that not be enough? And so even though I know I couldn’t save him because this was a battle he had to fight on his own, I’m always going to live with regrets.”

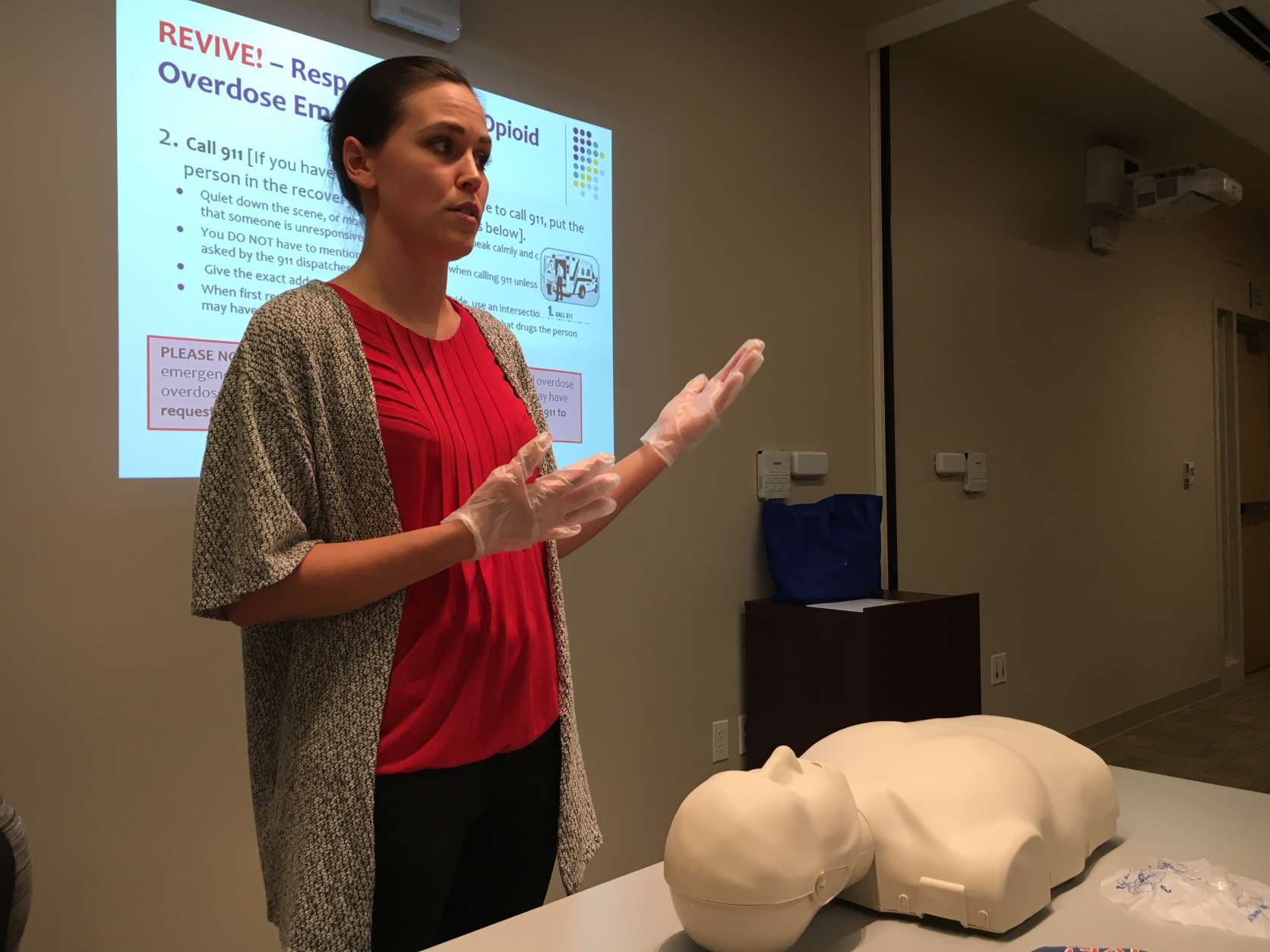

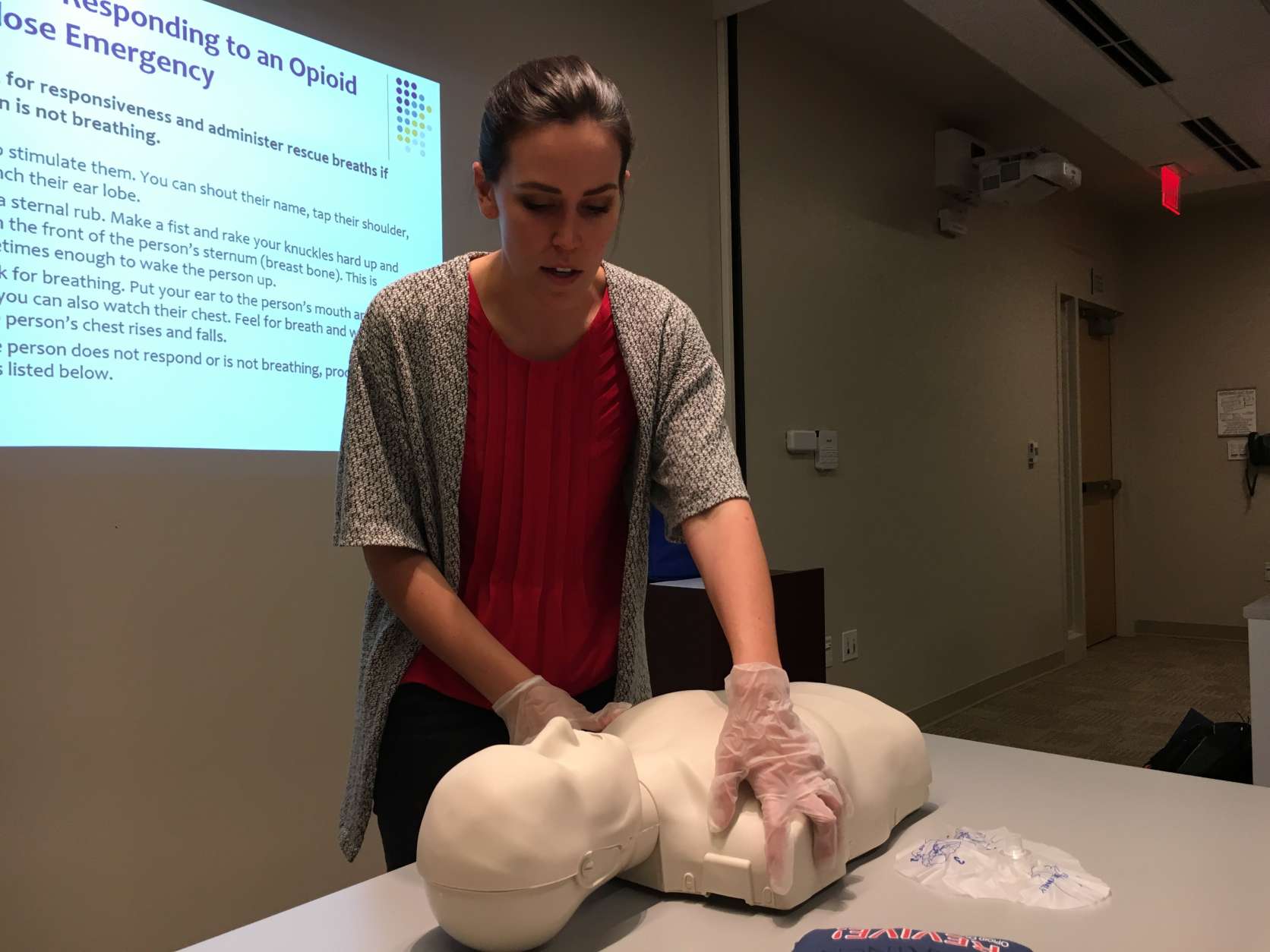

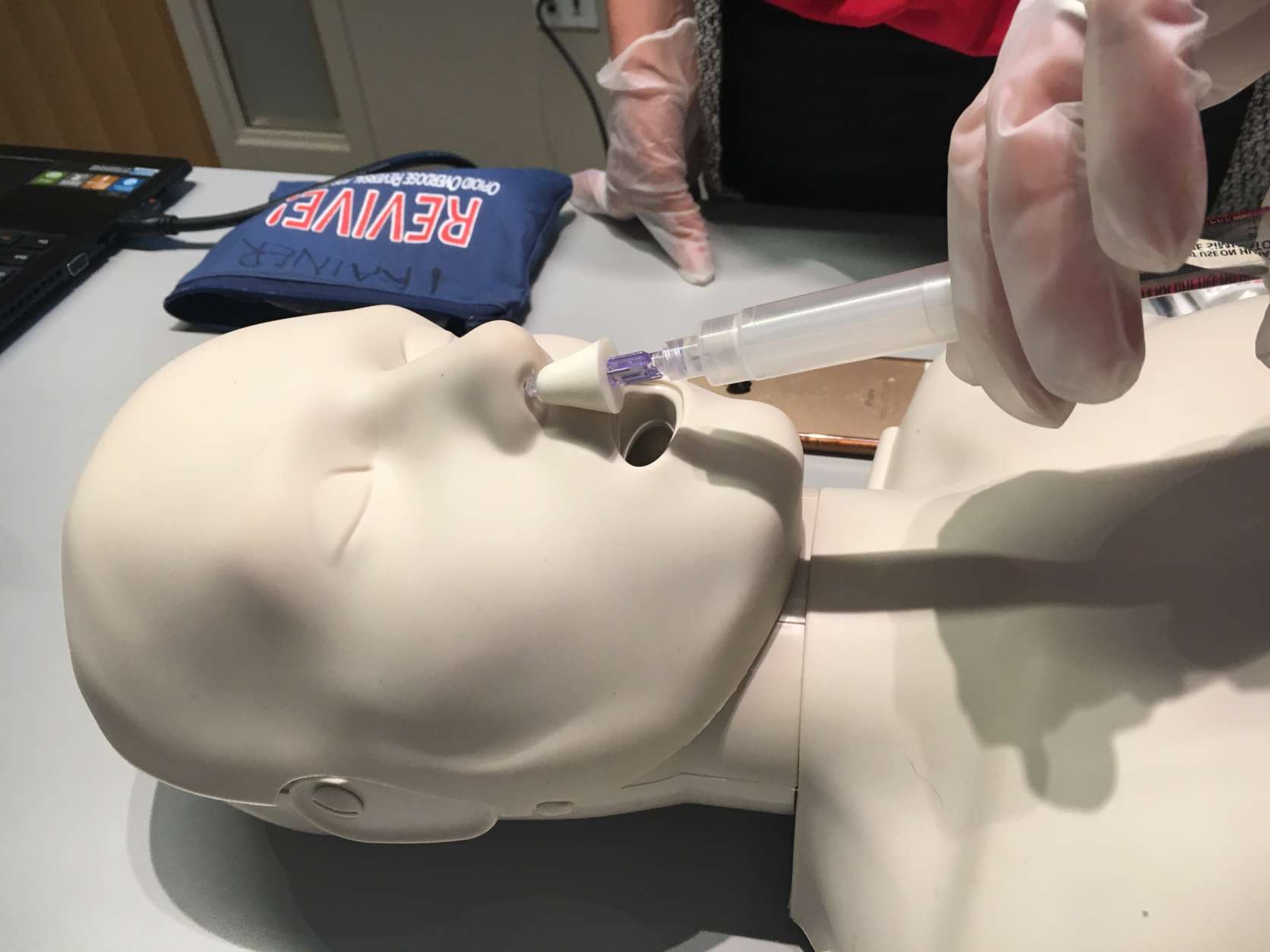

In her brother’s memory, Lovitt started the Chris Atwood Foundation to educate the public and provide resources. The organization partnered with the Fairfax County Community Services Board and the Virginia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services to create REVIVE!, Virginia’s opioid and naloxone education program. She became a certified instructor and now teaches classes on how to administer naloxone.

Since 2015, she has trained more than 200 people who, in turn, saved at least 10 lives. But that barely scratches the surface of the problem. Only a handful of residents attend these classes every month, despite the fact that Fairfax County is home to more than a million people and heroin deaths there doubled between 2013 and 2014.

“We should be seeing a lot more people, so there’s progress to be made to get the word out,” she said.

Naloxone laws

While Virginia’s standing order makes it easier for people to buy naloxone, Maryland and dozens of other states go one step further.

“One of the main ways that Virginia is a little behind, compared to Maryland, is we don’t currently allow REVIVE! opioid overdose instructors to dispense naloxone to their class participants,” Lovitt said.

Once completing the class, the participants then need to buy naloxone at a pharmacy.

“Unfortunately, there are a lot of reasons — logistical, financial, stigma-related — [why] people can’t get it from the pharmacy, or they choose not to. So a lot of people are getting trained and not getting the medication afterwards,” she said.

Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe promised that the opioid crisis will be a focus of this year’s General Assembly. A bill, introduced with bipartisan support, would allow REVIVE! Instructors, like Lovitt, to distribute naloxone directly in their opioid response classes.

Maryland has trained more than 37,000 residents to use naloxone properly.

It’s proven effective in counties all over the state.

“It’s shocking to hear that [in 2015] in Montgomery County, over 40 people overdosed and were saved by Narcan.” In 2016, “that number has tripled,” said Montgomery County Assistant State’s Attorney Steve Chaikin.

Meanwhile, the District has been much slower to adopt laws aimed at increasing access to naloxone. Until recently, friends or family members who may be in a position to help a person experiencing an opioid overdose could not obtain naloxone. Now, under a new law that goes into effect this year, doctors or pharmacists in D.C. will be able to write them prescriptions.

Combating the stigma

Now that the drug is available without a prescription in Virginia, officials hope more people will purchase it for themselves or loved ones who are dependent on opioids.

But Lovitt said the stigma is hard to overcome.

“People are afraid to go to the pharmacy counter and ask for this medication in public, because that would constitute admitting that they have a problem with addiction, or that their loved one does,” she said.

And the stigma extends to treatment and recovery facilities such as sober living homes, which don’t always stock naloxone.

“In recovery homes, there are a lot of people who are very early on in their recovery, and unfortunately, that means that they are at a higher risk for relapse. That means these places are the perfect spot to have naloxone and [it’s] really necessary to get it there.”

Lovitt said many private facilities don’t have a naloxone protocol in place, because it might send a message to family members that this is a place where a loved one can come to relapse.

A tool, not a cure

Naloxone, also available under the brand name Narcan, is a wonder drug that gives someone a second chance at life. But Second Lt. James Cox III, a supervisor for the Fairfax County Police Department’s organized crime and narcotics division, said it can also be a crutch.

“It can be the godsend and it can also be the biggest nightmare,” said Cox. “Now we have reports that drug dealers are actually giving their customers Narcan with their heroin.”

Lovitt said one of the myths surrounding naloxone is that the drug enables people to continue abusing drugs.

“When somebody is addicted to opioids and they’re given naloxone, it puts them into immediate withdrawal and it is pretty acute withdrawal. They do not want to have naloxone used on them,” Lovitt said.

But most experts agree that although naloxone saves lives, it doesn’t put people on a path to recovery and it is not a cure.

“What we need is a lot more availability to treatment, because otherwise, individuals who are saved from overdosing are going to continue to use the drugs and may overdose again. So we’re just forestalling the problem instead of actually trying to address it,” said Warren Bickel, director of the Addiction Recovery Research Center at the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute.

Bickel emphasized that addiction is a chronic disorder and that long-term treatment should be the top priority.

“Imagine the outcomes that you would see if you took other chronic disorders, like Type 2 diabetes or asthma, and just treated it for a short period of time,” Bickel said. “It would be nothing but a medical disaster waiting to happen. Short-term treatment for individuals with opioid dependence, [addiction] to heroin or prescription opioids, is better than nothing. But it’s not really going to address the problem.”

Out of death’s grasp

The Anne Arundel County Police Department was one of the first in the region to train and equip officers with naloxone kits, under former Chief Kevin Davis in 2014.

“If we did not have naloxone, our fatal overdose numbers would be double what they are. And they’re double what they were last year anyway,” said Police Chief Tim Altomare.

He called increasing access to naloxone a “no-brainer,” and said first responders are “using it every day, probably multiple times a day in the county.”

Police often arrive to the scene of an overdose faster than the fire department, Altomare said. And when it’s a heroin overdose, time is the greatest factor determining whether someone lives or dies.

Gina Chen was an Anne Arundel County firefighter and paramedic for nine years before she joined the police department as an officer. She has administered naloxone several times, most recently in May, when a woman overdosed on heroin.

Chen was the first person to respond. “When I got there, a 19-year-old female was lying in the street and her friend was screaming hysterically.”

The overdose victim carried naloxone with her, but her friend didn’t know how to administer it. Chen noticed that the woman was barely breathing and that her lips were turning blue.

She acted quickly, and within a minute, the woman began to regain consciousness. If left untreated, the woman would have succumbed to cardiac arrest. But it wasn’t the first time she come so close to death. Her friend said she had overdosed before.

In Friday’s final story of this series: Lawmakers and advocates face off over what should be done to end the heroin epidemic.