EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the third story in WTOP’s series “Hooked on Heroin: Deadlier than ever,” investigating the risk to children and young adults.

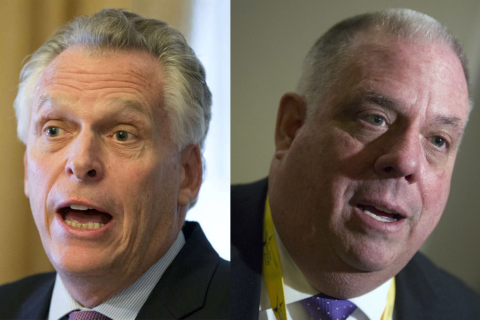

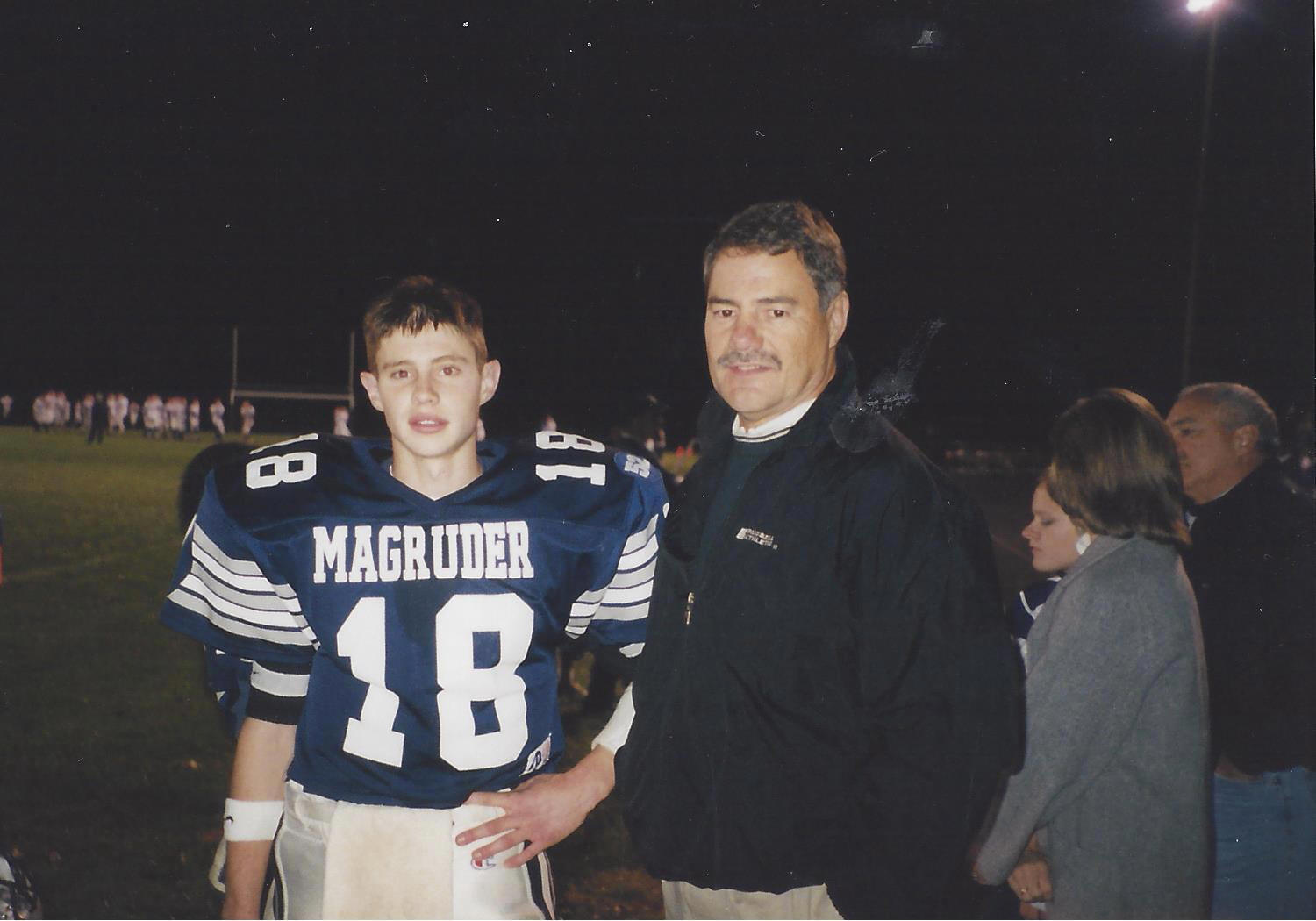

BETHESDA, Md. — A Montgomery County father said he tried everything to help his son, but he may have underestimated the power of his son’s addiction.

“Parents are clueless. Kids know so much more than the parents do. Parents are in denial and they don’t want to think this could happen to them,” Don Wood said. He admitted he was clueless, too, when his son Donnie first started struggling with opioid abuse. “He was so functional. We didn’t know. We didn’t understand addiction. It was a slow spiral downward.”

Looking back, he said he and his wife should have sought professional help earlier, when his son was in middle and high school. “It is just brutal for parents because you know you are making life-and-death decisions by doing something or by not doing something.”

Don Wood is not alone. More than two dozen other Montgomery County families have lost a son or daughter in the last two years to an opioid overdose.

As Americans stock their medicine cabinets with more and more prescription pills, children are getting caught in the crosshairs. Between 1997 and 2012, the number of children hospitalized for opioid poisonings nearly doubled, according to a December study by the Yale School of Medicine. The data showed toddlers and older adolescents were the most vulnerable. Meanwhile, heroin overdoses in teens jumped 161 percent. Teenage methadone use surged 950 percent.

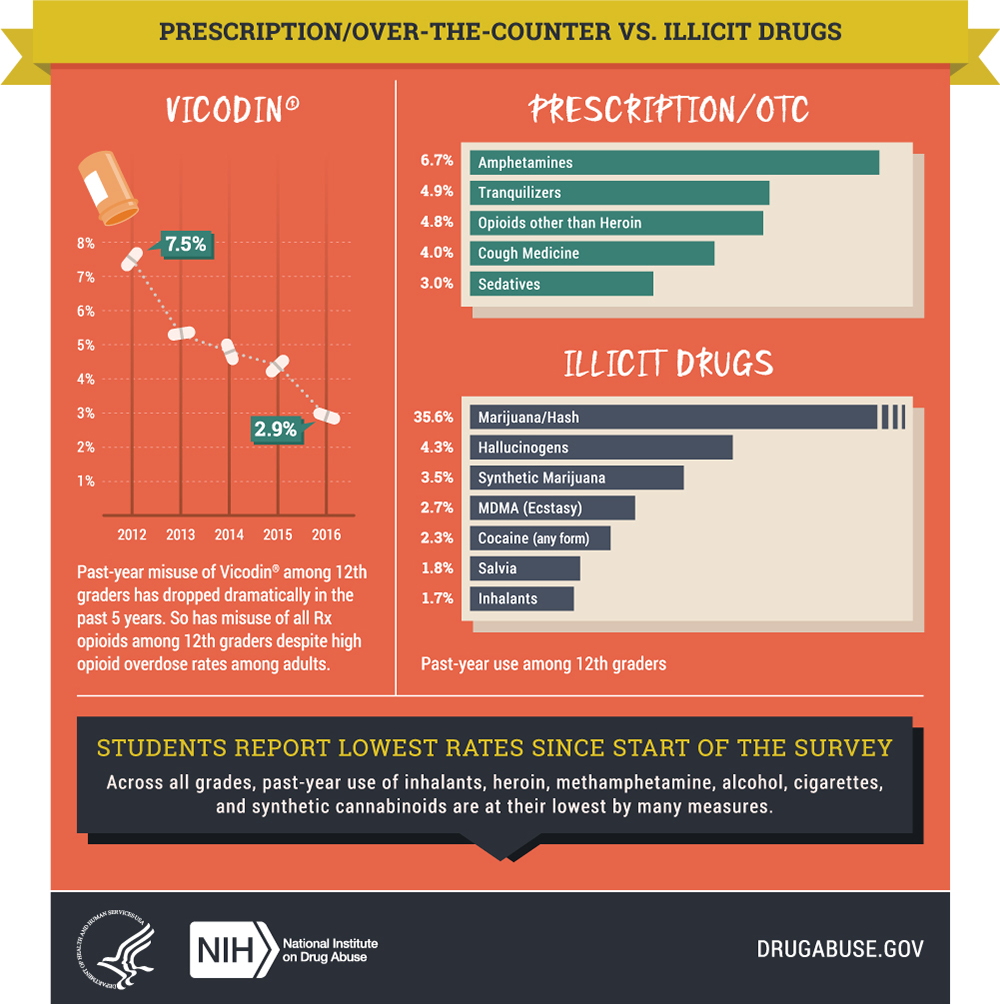

But there is good news. Since that survey, teenage substance abuse has actually dropped overall to its lowest recorded level.

From 2012 to 2016, the National Institute on Drug Abuse found a 4 percent drop in the misuse of Vicodin among 12th-graders. Across all ages, the use of inhalants, heroin, methamphetamine, alcohol, cigarettes and synthetic opioids fell. The dramatic decrease might be in part to the revamped education and outreach programs now available in local schools and communities.

But everything changes after high school.

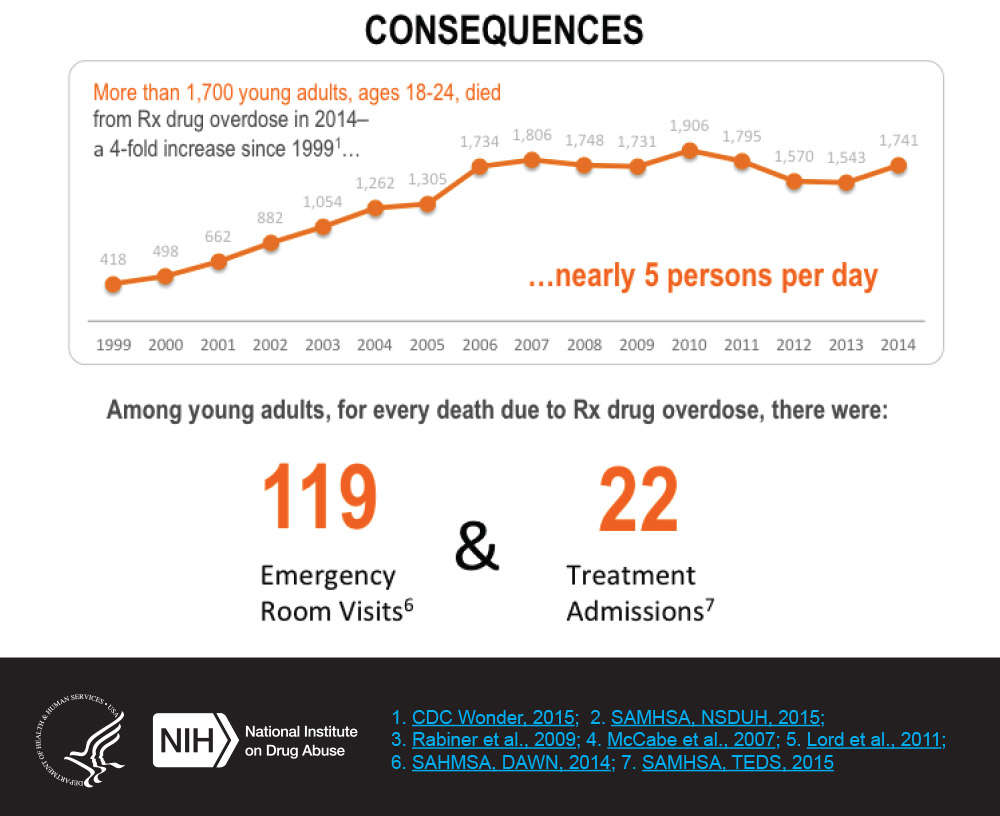

Young adults, ages 18 to 25, are the biggest abusers of prescription and opioid painkillers.

‘What do you do?’

Wood and his wife helped their son go through two rounds of short-term drug rehab. They let him move in with them. They kicked him out. They supported him financially into his early 30s. They gave him ultimatums.

But despite their repeated attempts to get him on the right track, at age 32, Donnie overdosed on Tramadol, a synthetic opioid painkiller. When Wood found his son’s lifeless body on his bed, for a split second, he felt a wave of relief.

“Just a tremendous sense that he’s at peace. We’re all at peace,” Wood’s voice quivered. “That lasted for a brief second. I just felt it wasn’t him. He’s not there. He’s somewhere else. That was just his shell.”

Of course, that moment was immediately followed by an overwhelming sense of grief that continues to this day.

Wood knows being a parent of a child with substance abuse disorder can be confusing and lonely.

“Everybody’s trying to find that line. What do you do? You want to help because you’re the parent. You want to help fix this. They are your child. You brought them into the world,” Wood said as his eyes filled with tears. “You’re responsible for them. You’ve raised them since they were little babies. So you want to fix this.”

When speaking to parents and teenagers about opioid addiction, he reminds them that it can — and does — happen to families like theirs. He advises parents to search their children’s rooms and cars if they suspect a substance abuse problem. Controlling medications within the home is critical.

“You want them to grow and develop, and be all they can be. But on the other hand, you want them to be alive and not addicted,” he said.

Scaring them straight

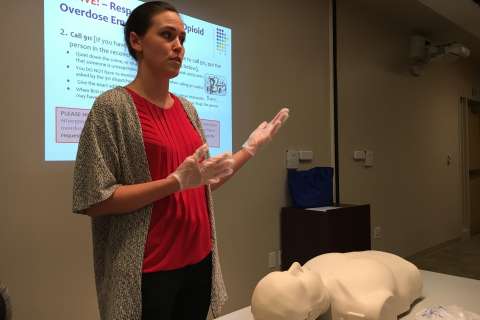

As heroin and painkiller deaths rise, local law enforcement agencies are pushing to tackle school drug education in a new way.

Instead of just teaching children to resist peer pressure, like the 1980s-era “Just Say No” campaign or the D.A.R.E. program, officials are showing students the real-life consequences of opioid addiction.

Anne Arundel County Police Chief Tim Altomare wants an age-appropriate graphic curriculum.

He believes middle schoolers should see photos of the abscesses in a heroin addict’s arm and high schoolers should see a dead body after a fatal overdose.

“I’d rather have their sensibilities offended for that brief period of time than have them become addicted to heroin and end up on the slab in the morgue,” he said.

The county’s new Not My Child program brings speakers from the police department and treatment coordinators from Pathways Alcohol Drug Treatment Center to families with school-age children. It’s open to anyone — even if you don’t live in the county.

Montgomery County’s Speak Up, Save a Life presentations shows high schoolers a documentary with firsthand accounts of heroin abuse. Survivors share heart-breaking stories of loss. Prosecutors, such as Assistant State’s Attorney Steve Chaikin, educate students about a new law which stipulates that anyone who calls 911 at the scene of an overdose will not face misdemeanor drug or alcohol possession charges.

“The government has a compelling interest to protect the lives of many rather than prosecute somebody for possession of alcohol or drugs or paraphernalia,” he said. “The new law is a game-changer.”

Kids and sports

One sports injury or surgery could start a downward spiral for vulnerable kids who don’t have the tools or maturity to manage painkillers themselves.

Opioids are becoming more accessible to everyone, and particularly for teenagers, the physiological aspects of addiction can be life-changing.

Altomare cautions parents to think twice about filling a prescription for painkillers for their child, because once the prescription runs out, heroin becomes a much more attractive and inexpensive temptation for an addict.

“When a kid who had knee surgery takes 30 OxyContins out of a doctor’s office, it’s a problem. It’s absolutely a gateway … It becomes much easier for someone fighting this fight to get two gel caps of heroin for $20 than it does to get an 80 mg OxyContin for $80 or $100,” Altomare said.

Second Lt. James Cox III, a supervisor for the Fairfax County Organized Crime and Narcotics Division, has investigated cases where children have stolen their ill grandparents’ fentanyl patches to sell on the street or take themselves.

“The youngest (opioid addict) I’ve seen so far is 14 years old in Fairfax County,” Cox said.

In 2015, the FDA approved the use of OxyContin for children between 11 and 16 years old, primarily for pediatric cancer patients, but the risk of abuse is high.

A recent Yale study found opioid overdose cases in teenagers ages 15 to 19 increased 176 percent, and heroin poisonings jumped 161 percent, between 1997 and 2012. Young adults are also at risk. Prescription painkillers were responsible for a 165 percent increase in overdoses among that age group.

“Listen to your children. If they’re suffering, seek help. Don’t hide from this. If we avoid this problem, it’s resulting in death,” Chaikin said.

The youngest victims

Childhood hospitalizations involving opioids such as Vicodin and OxyContin have spiked nearly 300 percent in recent years, according to a Yale School of Medicine study.

“They’re eating them like candy,” said lead researcher and Yale fellow Julie Gaither.

From 1997 to 2012, the number of poisonings poisonings toddlers jumped more than 200 percent.

Even babies are not immune from the crisis. As the problem grows, local hospitals are changing the way they respond to newborns suffering from opioid withdrawal. New research shows babies born with an addiction increased fivefold between 2000 and 2012.

The Children’s National Health System, in Virginia, has worked to treat the smallest victims with a new protocol in the three NICU centers: Mary Washington, Sentara Woodbridge and Virginia Hospital Center. Each newborn is assessed for their risk and a score is calculated based on the severity of their condition.

In Maryland, standardizing care and treating infants experiencing withdrawal has been a priority for the state’s 30 birthing hospitals. The Maryland Patient Safety Center has, over the past year, created the Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome Collaborative to tackle this issue. The initiatives aim to standardize the treatment plan for babies and decrease the time they stay in the hospital.

Read more on Thursday as the series continues: How states are getting lifesaving overdose-reversal drugs into more hands.