WASHINGTON — When Paul Pascal first visited Kolker Poultry at D.C.’s Union Terminal Market in 1955, he had no intention of returning.

He arrived in his full Air Force Band uniform to visit his girlfriend’s family business, but was quickly turned off by the inner workings of one of the region’s largest poultry distributors.

“I actually said I’d never come back there, and here I am talking to you today,” Paul said.

Paul not only returned to the city’s wholesale market district, he married into the business, and over the years has become one of the most prominent players in the market’s history and modernization. In fact, he’s come to be known by many as “the mayor of the market.”

From sausages to souvenirs

Paul isn’t entirely sure how the nickname came about, but says it’s likely a result of his efforts in preserving parts of the historic 45-acre district — sometimes called the Capital City Market and the Florida Avenue Market — bound by New York and Florida avenues in Northeast.

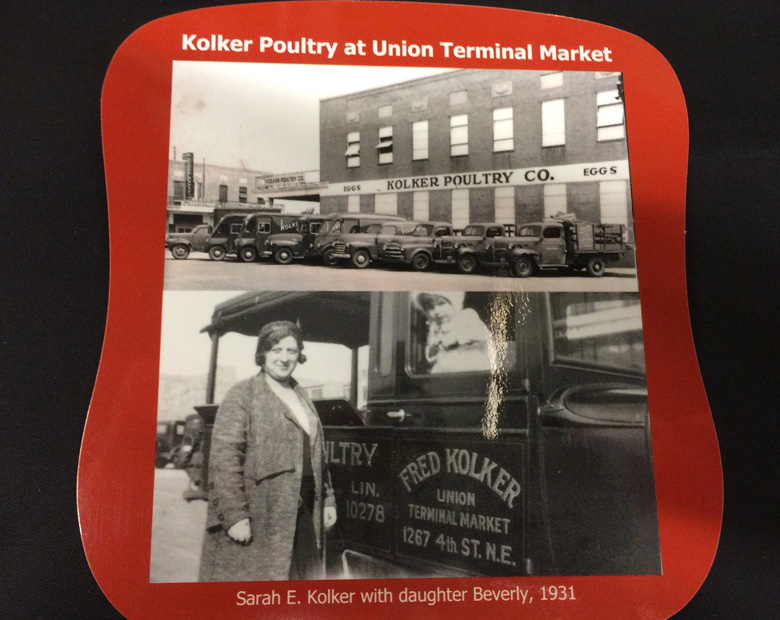

Kolker Poultry was founded in 1930 by the father of Brenda Pascal, Paul’s wife. The family set up its business on the northeast and southeast corners of 4th and Morse streets in the heart of the market area.

“The market was quite an interesting place. Everybody knew everyone,” said Brenda, who also had cousins on both sides of her family own businesses in the wholesale hub of the city.

During the week, distributors would process and sell their products to local stores and restaurants. Up until the early 1960s, the market would open to the public on Saturdays, and vendors would sell their meats, cheeses and eggs.

Paul established his law office at the market in 1966, and quickly became involved in its politics. In his first year, he represented an association of food distributors, many of whom owned businesses at the market.

In the 1980s, then-Mayor Marion Barry wanted to make improvements to the market, including adding dock-level warehouses to make loading and unloading more efficient. (The warehouses in the Union Market area are ground-level.) He tapped Paul to head up his own association of market business owners, of which he eventually became president.

Despite Barry’s best efforts, many of the larger wholesalers, including Kolker Poultry, eventually moved their businesses to larger, dock-level warehouses outside the city. But Brenda’s father held on to his real estate in the market district.

“When that happened, you started getting a potpourri of different types of people,” Paul said about the market, which was predominantly run by Italian, Greek and Jewish families in its early years.

He says Korean, African and Caribbean distributors moved to the market district to launch their businesses, selling everything from wholesale souvenirs to specialty foods from their respective regions.

“So when you go through the market today, it’s quite a mixture of products, and it’s nice to see,” Paul said. “But it was the transformation from ground-level to dock-level that forced the change.”

In 2006, an initiative called New Town was introduced, which essentially proposed to level the entire historic market area.

Brenda, who is passionate about maintaining aspects of the market’s original identity, called the bill “disgusting.”

“I think it takes away the charm and what was there,” she said. “You can build any big building and do anything, anywhere, but the market is a unique place and has always been that.”

In reaction to New Town, Paul reignited his former association from the 80s and “successfully avoided having the market torn down” by making sure private owners secured a significant portion of the market.

“I figured if we could get control of the four corners, they’d never get the 50 percent,” he said.

At the time, the Pascals owned two of the corners, and convinced Bruce Baschuk, of developer J Street Companies, to secure the other two. Edens, a South Carolina-based development company, started buying up properties in the area as well.

“So there’s a whole mixture of major players now,” said Paul, whose family now owns 12 addresses in the market district. “And somewhere along the line, because of my involvement, someone called me ‘the mayor of the market.’”

The modern market

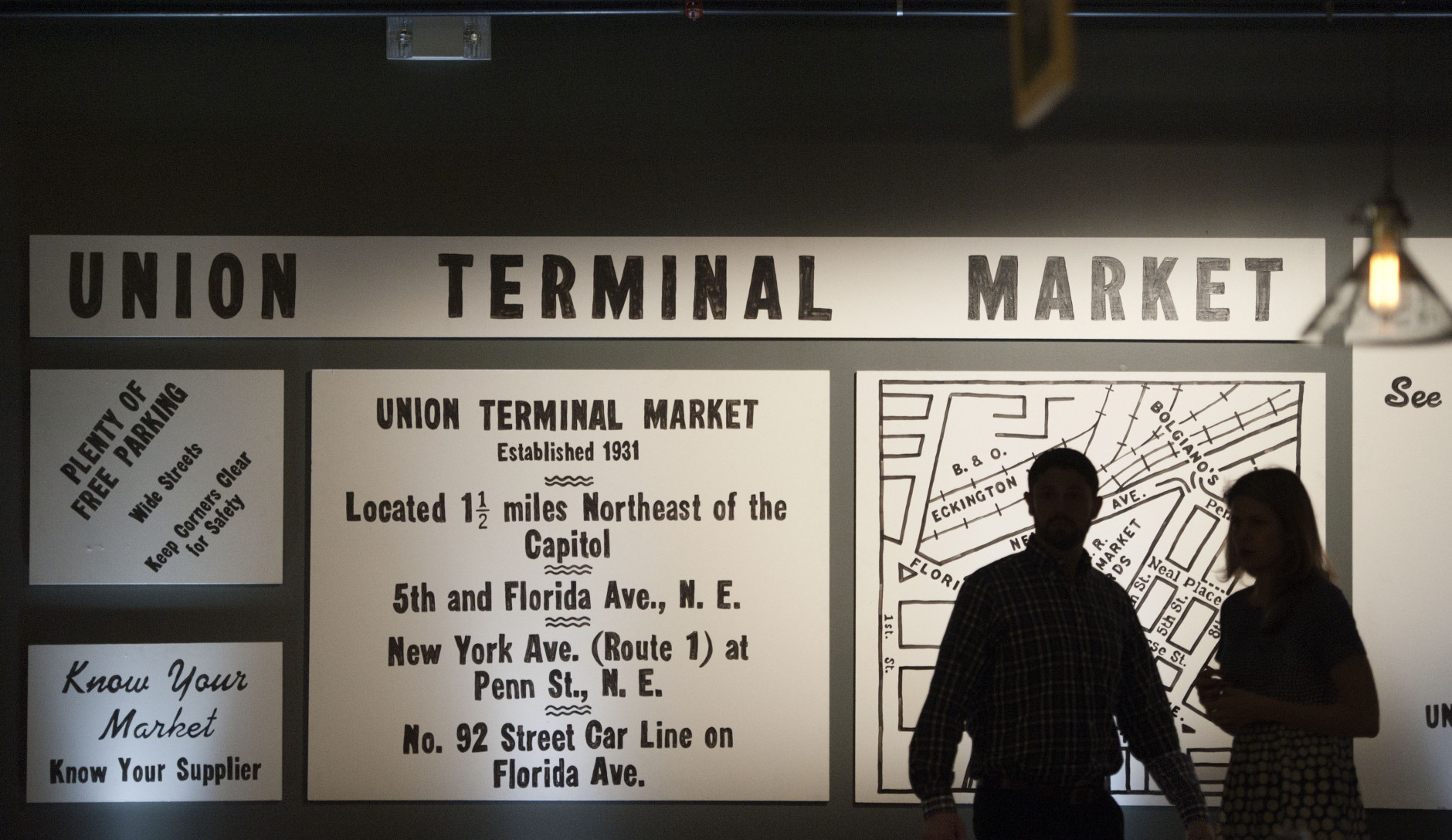

The Capital City Market area witnessed its biggest change in 2012, when Edens opened Union Market, a 25,000-square-foot space that is home to 40 regional and international food vendors in the old Union Terminal Market.

In the past four years, Union Market has become one of the most innovative and celebrated destinations in the city. Bon Appétit listed it as one of the top 5 food halls in the country; the first lady and celebrity chefs have hosted events there.

The success of the revitalized market quickly spawned additional development in the area. Independent movie theater Angelika Pop-Up, Dolcezza’s gelato factory and the upscale Italian restaurant Masseria have opened within blocks of Union Market.

“We love going there. I mean, you go there on a Saturday or Sunday, and you see all of the young families and people walking around. It’s a wonderful thing. It’s a vibrant area now,” Paul said.

In June, Edens broke ground for a 20,000-square-foot Latin market at 1270 4th St. NE, headed by chef Jose Garces. The food emporium will anchor an 11-story mixed-use building comprised of 400 residential units and 30,000 square feet of retail.

Paul says he’s not surprised by the fresh retail that’s moved in — citing similar redevelopment projects in other historic markets in New York, Philadelphia and Portland, Oregon — but he never thought residential units would become part of the market’s culture.

“As long as the millennials keep coming into town, you’ll have it. Because they need places to live,” Paul said.

In the next few years, he predicts more restaurants will come to the area as well.

“Who would have dreamed?” he said about Masseria’s success thus far. “They really are pioneers in terms of fine-dining in the market, and you will see more as time goes on. It’s ideal.”

Brenda says as long as the building’s facades remain as true to the originals as possible, she’s fine with the changes.

“I know the wholesalers aren’t going to come in like they used to and do the things they used to do. I understand that. But I will fight … to keep the original buildings in tact, as they are,” she said.

If her father saw the market today, Brenda says he’d likely “be surprised.” Paul says he thinks the former business owner, who died in 1993, would “love it.”

“He was a progressive, far-thinker. And I think he’d be very happy to see what’s happening,” he said. “I think his goal in raising the daughters and the family was to get real estate and pass it on to the next generation.”

Paul and Brenda Pascal talk about the history of Union Market: