The Rev. Barbara Brown Taylor was attending a seminar one day when someone asked her a question that she hasn’t been able to forget.

“What is the story you are working on that doesn’t have an ending yet?”

Taylor gave one answer that day but today she has another: The story she can’t quite figure out is her own.

On the surface, Taylor led a life that most people would envy. She was a widely sought-after speaker whose sermons were compared to “literary gems.” Her books made the New York Times’ best-sellers list. One made the cover of Time magazine. She appeared on Oprah Winfrey’s “SuperSoul Sunday” show. Strangers approached her in grocery stores with reverence and awe.

But something happened to her as her reputation spread. She found herself drawn to “someone else’s rose.” She began to see beauty and truth in other people’s religions. And she became so disillusioned with her own that she “could not look it in the eyes.”

Taylor once called herself a “detective of divinity” for her ability to collect evidence of God’s genius. But her spiritual wandering made her feel at times as if she was guilty of a crime.

“The fear rose up from a more primitive part of my brain that had been taught to fear a jealous God’s wrath if I did not love him and him alone,” Taylor says.

This was the plot complication she faced in her story: What do you do when you’re the superstar preacher, but you fall in love with other faiths more than your own?

Easter morning would help give her an answer.

A voice for anxious times

A story about doubt may seem like an odd topic for an Easter weekend. The traditional Easter message is one of triumph: Jesus conquers death and sin through his resurrection. But this is a tough Easter for many Christians. Many don’t feel so triumphant.

Christianity is in crisis. Catholics are losing faith in church and clergy because of an ongoing sexual abuse scandal. Mainline Protestant churches are splitting apart over issues such as gay clergy. There are now more Americans who claim no religion than there are evangelicals and Catholics.

When the Notre Dame Cathedral recently erupted in flames, some saw it as a sneak preview of the church’s future in the US. They warned that American churches are heading toward collapse. They envision a post-Christian future like Western Europe’s: rapidly emptying churches and soaring cathedrals that no longer speak to people.

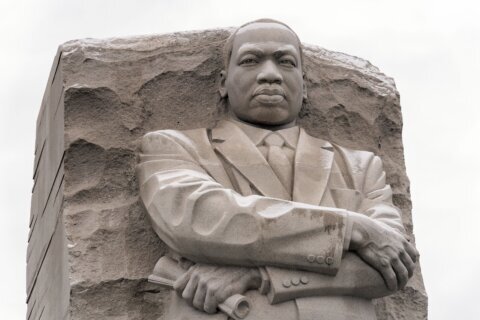

Few, if any, contemporary Christian leaders speak to the spiritual restlessness of this time like Taylor. In her books “Leaving Church” and “Learning to Walk in the Dark,” she always seems to be in motion — leaving one spiritual rest stop for another exit down the road.

She has “near perfect pitch” for speaking to people’s fears without leaving them hopeless, says the Rev. Thomas G. Long, another celebrated speaker. He was recently selected, along with Taylor, as one of the 12 most effective preachers in the English language in a prestigious preaching survey.

“She has such powerful gifts of language and narration that her readers and hearers find their own questions and concerns coming to expression in ways that prompt them to say, ‘Yes, yes that’s what I feel,”’ Long says.

Why Taylor is scared of true believers

What Taylor is feeling on this recent afternoon is hungry. It’s lunchtime when she receives a visitor at her secluded farm in the northeast Georgia mountains.

Now 67 with a mass of dazzling white hair, Taylor motions to a spread in her kitchen that she’s prepared for her guest.

“Deviled eggs, good turkey sandwiches,” she says pointing to the food. “You eat the rest because I’m not going to.”

Taylor’s farm looks as picturesque as a postcard: rolling meadows, mountains looming on the horizon, a sprawling porch decorated with swings and cushions. She even has a small writing cabin near her house where she goes to work without distractions.

One of her dogs greets the visitor at her farm’s entrance with a few desultory barks. Then he trots away to frolic in a meadow. He has plenty of company. Taylor has two horses, two dogs, four cats, 11 guinea hens and more chickens than she can count.

She shares the farm with her husband, Ed. They married in 1982, a year before she was ordained as an Episcopal priest. Fourteen years her elder, he was never intimidated, she says, by a woman in a clerical collar.

“We’ve both been stung when people shake my hand and completely ignore him,” she says. “He doesn’t travel with me much for that reason, and it’s a great relief to me that he doesn’t because when I come home from a trip, he’s there like the pool of fresh water at the end of a dusty road.”

Taylor has been traveling a lot lately to promote her latest book, “Holy Envy.” It describes what she calls the “shock of meeting God in so many new hats” when she taught a course on world religions at Piedmont College, a liberal arts school in north Georgia.

The book carries on Taylor’s tradition of what she calls, “saying things you’re not supposed to say.” She takes on questions that annoy some Sunday school teachers: Is Jesus the only way? Are all religions alike? If I love Buddhist meditation, can I still call myself a Christian?

The book has attracted plenty of praise. Book critics and journalists tend to love Taylor’s work. Time magazine once said that her writing “rivals the poetic power of C.S. Lewis and Frederick Buechner.”

Yet her critics often react just as strongly to her work.

Some say she waters down Christianity’s core beliefs with a self-indulgent theology of “happy faces and pumpkins in the sky.” Others say she should add some social justice to her message — try less poetry and be more prophetic.

But others say her message is needed more now than ever. After Taylor spoke at Concordia College-Moorhead in Minnesota, Jacqueline Bussie, director of the Forum on Faith and Life at the school, said more Americans need to get a dose of holy envy.

The US is the most religiously diverse nation in the world, but “in this country you can graduate college and still have no clue about the religious practices, world views, and history of billions of people,” says Bussie, author of “Outlaw Christian.” “This is negligence.”

In person, Taylor is playful, expressive with her hands and self-deprecating. But her voice rises in exasperation when she recounts how some Christians depict her as an outcast pastor.

She calls them the true believers.

“True believers are among the meanest people I’ve ever met,” she says, stretching out her legs in a cozy living room filled with books on poetry, religious icons and a photo of her posing with Oprah.

“I cannot think of anybody of another faith who has wounded me like Christians,” she says. “Judged, condemned to hell, cast out of the body of the faithful — look me up online.”

Taylor, though, became one of her own harshest critics when she experienced a spiritual fear that she never saw coming.

A pastor who does a little spiritual ‘sleeping around’

Her spiritual crisis had no dramatic backdrop — no spiritual breakthrough on some vision quest alone in the woods. She says she lost her way in the church after she found a new home in the classroom.

When she started to teach a college course in world religions, something odd happened. She was enthralled when teaching students about other faiths and taking them on field trips to mosques, temples and Buddhist centers. But when the class syllabus turned to Christianity, her fire sputtered.

She started to feel as if she was spiritually “sleeping around.” She started collecting Tibetan singing bowls, Hindu deities and Muslim prayer rugs. She felt as if she was a spiritual shoplifter.

But she was no mere theological tourist.

She started to see beauty and truth in other religious traditions.

She was impressed by Buddhists because they weren’t interested in opposing any other religion or converting anyone.

She was astonished by the graciousness of an imam who told her class after they visited a mosque: “Our deepest desire is not that you become Muslim, but you become the best Christian, the best Jew, the best person you can be.”

And she was ashamed to learn how much her own faith had “scorched” other religious traditions by the way the faithful treated non-Christians.

“Belittled, patronized, infantilized — treated as if they had never had a thought about the divine and sacred,” she says.

Taylor knew what she was taught: Jesus was the way, salvation is found in no other name, and at the name of Jesus every knee shall bow. But she also knew what she felt — something sacred was speaking to her even when it didn’t have the name Jesus attached to it.

In one “Holy Envy” passage she writes: “Through the years I have spent dozens of hours in the presence of Tibetan lamas who have spoken directly to my condition. Their talks have been as meaningful to me as anything I have heard from teachers in my own traditions… What can this mean?”

It couldn’t mean anything good when she thought back to her days following a fear-based Christianity that she thought she had abandoned. Scriptures that declared that God was a “jealous God,” and passages where prophets described those who turned to other gods as whores flashed in her memory.

“The fear surprised me because it wasn’t rational,” she says. “I had been a seeker long before I became a Christian so questioning everything was second nature to me.”

Taylor says she felt like a little child, scared that she would lose her heavenly father’s love forever.

How could she find her way back?

She opened her Bible and started reading about Jesus.

Where Jesus found loveliness

She was in for a surprise. Turns out the New Testament is full of Jesus’ interfaith encounters. Some of the best-known stories about Jesus depict his admiration for those outside his religion, she says.

She cites some of them in her book: Jesus being astonished by the faith of a Roman centurion who wanted his servant healed; the Samaritan leper who impressed Jesus with his gratitude; the Syrophoenician woman whose wit and love for her daughter caught Jesus by surprise.

They were all people who worshiped other Gods or worshiped the same one Jesus did in an unorthodox way, she says.

“If anything, the strangers seem to change Jesus’ ideas about where faith may be found, far outside the boundaries that he has been raised to respect,” she writes in “Holy Envy.”

Taylor amplifies the point from her living room. Her voice rises in volume. She’s no longer cracking jokes and laughing. She’s going into preaching mode.

“It’s all on the page,” she says. “It’s on the page in the Bible about Jesus dealing with women, Syrophoenicians, Canaanites and Greeks, and he’s not making distinctions. Nor is he trying to convert everybody. He’s just dealing with people who are hungry.”

Taylor stopped seeing herself as the wayward child risking God’s wrath because she was dazzled by the faith of others.

“Now I don’t believe Jesus is mad at me for finding loveliness in the faith of my religious neighbors because he did the same thing,” she says.

Taylor’s new Easter sermon

There are still nagging questions, though, about where Taylor stands with her own faith.

Have you stopped being a Christian?

“No, I haven’t,” she says. “So that means I’m very aware Jesus never commanded me to love my religion. He said love God and your neighbor. That’s about all I can handle day by day.”

Do you still go to church?

Taylor has gone to everything from a sprawling evangelical mega church to a tiny African-American Catholic parish and a storefront church in a strip mall in recent years.

“I worship every day,” she says. “Sometimes it’s in churches, but other times it’s around dinner tables, in airports, in city parks, and in the woods with wild turkeys.”

Those answers, though, are the kind of poetic musings that still make some Christians suspicious. Is she more than “happy faces and pumpkins in the sky?”

She doesn’t sound like a person who is giving up on Christianity.

In “Holy Envy” she writes: “However many other religious languages I learn, I dream in Christian. However much I learn from other spiritual teachers, it is Jesus I come home to at night.”

Easter morning also helps her find her way home.

She still believes in the Easter story. She just doesn’t believe that it represents the triumph of Christianity — proof that Christians have a monopoly on religious truth.

How can you believe in Easter without believing Christ is the only way?

The way she now talks about God in the Easter story helps explain why.

“These days I would say Easter is the eruption of life from a tomb as God’s huge surprise, going in a different direction, and if anything, proof that you can never predict how God is going to act next,” she says.

Taylor’s spiritual restlessness may continue to push her in different directions. But she no longer sounds afraid to look her faith in the eyes.

“Now I value Easter as the reminder that you never know where life is going to come from next, and there’s no sense being attached to the day before yesterday because the day before yesterday is dead, and today something is alive,” she says.

She leans forward on her sofa and her expression turns solemn. She gets a faraway look in her eyes, and raises her hands as if in worship.

“So why not follow the life, and see where it leads, with some kind of trust in the spirits’ ability to blow where nobody expected to blow, and in a direction nobody expected it to go into — and be willing to be blown away.”