How this ‘crooked duckling’ from Mexico became a professional ballerina in Manassas

1/10

1/10

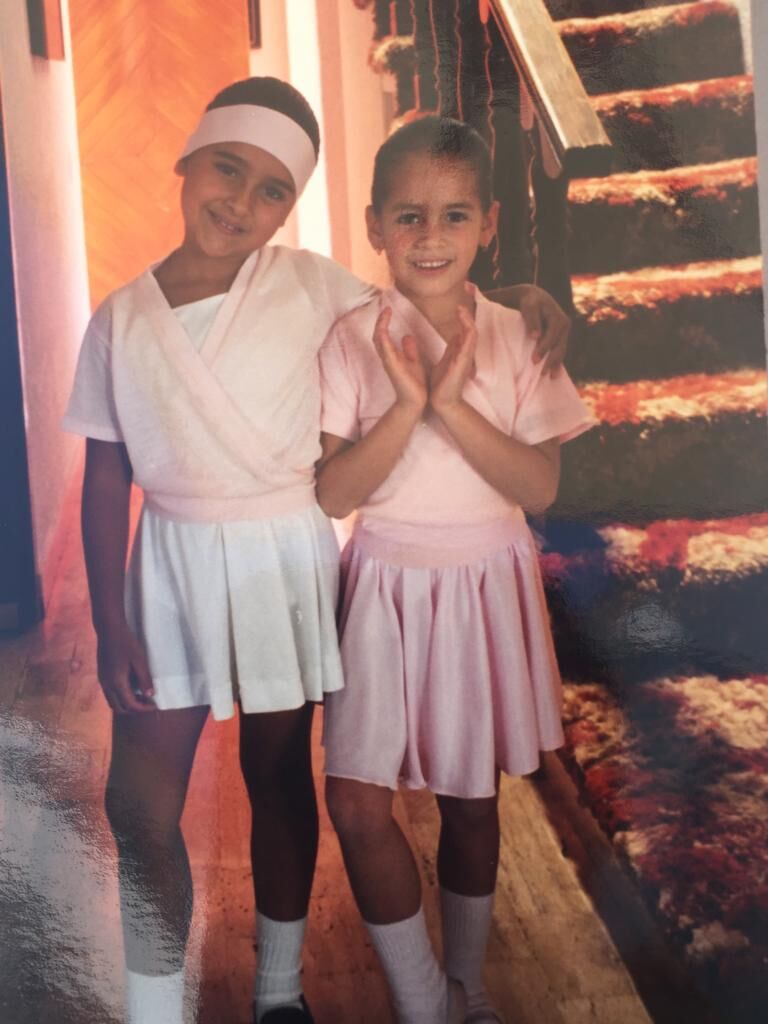

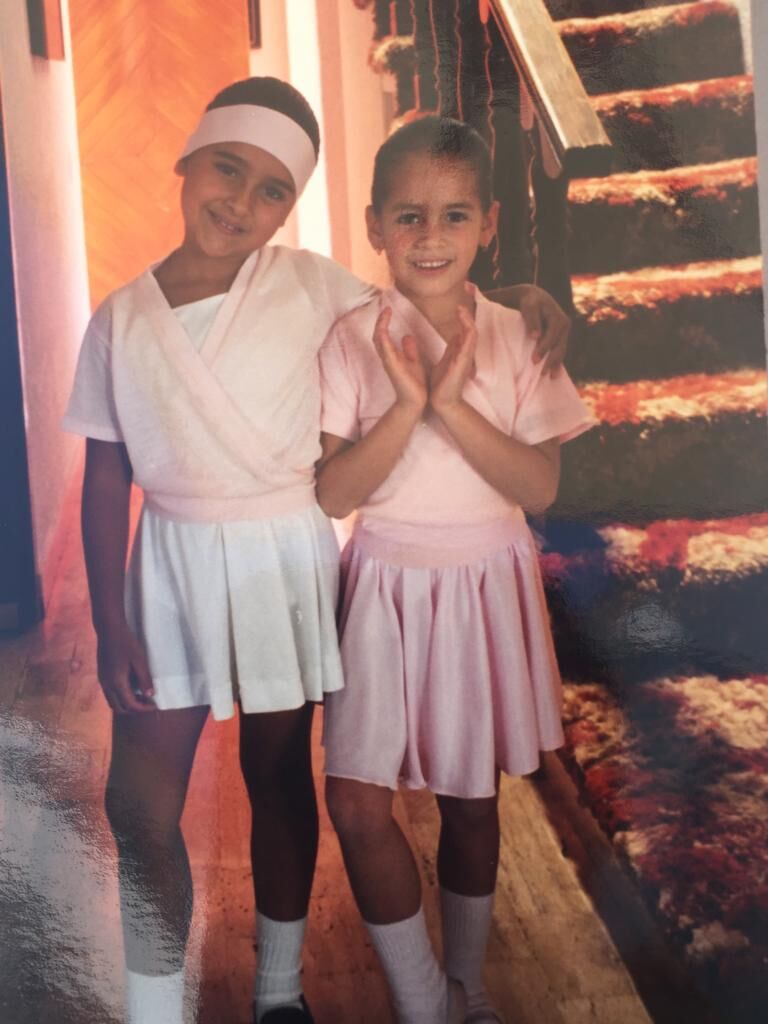

In a photo from her childhood, Dani Moya (right) poses alongside her cousin while dressed for dance class.

(Courtesy Dani Moya)

A ‘crooked duckling’ dreams of ‘Swan Lake’

Moya took up ballet at 4 years old under doctor’s orders.

“My doctor told my mom that I needed orthopedic shoes, because I walked like a duck with my toes facing each other and my tailbone was out,” Moya said.

The hope was that ballet classes at the small local studio in Mexico City would help her external rotation and posture, she said. But by the time she was 7 years old, she said she was sure she wanted to be a professional ballerina — even as some thought of her as “this crooked duckling.”

“But I just stuck with it,” she said. “My little, tiny studio in Mexico told me ‘OK, well, you do have potential. You should go to a bigger studio.’”

Eventually, with the help of a dedicated teacher, Moya began auditioning — oftentimes outside the country.

“Mexico is not very well known from dancing and there’s a ballet company in Mexico, but it’s not the living for a dancer,” she said, explaining that dancers are paid enough to make a living in places such as the U.S. but not Mexico.

Her family was worried about her chances at success. She said she didn’t have a “plan b” at the time, if dancing didn’t work out. Around 13 years ago, she auditioned for the prestigious Joffrey Ballet dance company in Chicago and was accepted as a trainee.

After landing several other company contracts, the dancer moved to Manassas about six years ago.

2/10

2/10

In relevé (translation: on her tippy toes), Moya arches back as she performs.

(WTOP/Jessica Kronzer)

3/10

3/10

Moya looks toward a mirror while she warms up her feet at the barre ahead of rehearsal.

(WTOP/Jessica Kronzer)

What happens to ballerinas when there’s no one around to dance for?

Another ballerina transplant to the U.S. is Moya’s roommate, Kurumi Miwa, a 25-year-old dancer from Japan who has been with the Manassas Ballet Theater for three years.

“I’m living for ballet,” she said. “I came from Japan. I’m coming here for dancing, not just doing a job.”

Doing that job became complicated around March 2020. Miwa was in the U.S. on a study abroad program and auditioning for ballet jobs when COVID-19 lockdowns stunted most productions.

Miwa was among the dancers who said they were “struggling to find a place to dance.”

Both Miwa and Moya signed contracts with the Manassas Ballet Theater during the pandemic.

“They kept our dancers dancing with a paycheck, and they never stopped,” Moya said of the company. “They kept performing, even if it was through Zoom.”

Continuing to dance was about more than just a paycheck.

“We kind of lose a sense of identity without dancing,” Moya said. “Manassas Ballet Theatre really connected with me in that area.”

Grant Wolfe said it was never a question of whether the ballerinas would keep dancing — but how.

“I try to make all things possible that if you can’t go right, you go left, if you can’t go up, you go down. You figure it out,” Grant Wolfe said.

When the pandemic lockdowns began, the dancers were scheduled to have a performance that weekend. Grant Wolfe postponed the show and moved up the dancers’ spring break to figure out next steps for the studio.

That one week break was the only time the dancers weren’t working during the pandemic, she said.

For the students’ recital in spring 2020, Grant Wolfe bought a pipe and drape, which covered up the ballet bars and made the studio appear more theatrical.

The studio took precautionary measures to prevent spreading the virus — including performing without an audience. Instead, parents could watch a recording of the recital afterward.

By September, the professional company was putting on virtual productions using that same method.

“We wore masks and we changed the choreography so no one would be touching hands or anything like that,” Grant Wolfe said. “Any partnering was done by married couples.”

None of the dancers got sick with COVID-19 during that period, and she said the performances were valuable to those confined to their homes, separated from family and friends.

“Everyone was so hungry for life,” Grant Wolfe said. “People really welcomed the chance to at least see the dancers, even if it was on a computer screen or a TV screen.”

Part of why these performers love dance, in general, is because of the value is holds for the audience.

“They think that it’s too highbrow for them, that they won’t understand what’s going on,” Grant Wolfe said. “But dancing is instinctual. It’s a way of communication from prehistoric times.”

Moya said ballet is more than “a tutu,” and it’s worth cultivating, though it’s sometimes overlooked by mediums like painting or film.

“Dancing is a real job. And it’s an art form. And it’s worth fighting for,” Moya said. “Theater is very important part of our community, and it helps a lot of people.”

4/10

4/10

Moya performs a solo ‘La Bayadere,’ and stretches her leg toward the ceiling while balancing squarely on pointe.

(WTOP/Jessica Kronzer)

5/10

5/10

Dancers reach out while seated with their legs pointed toward the corner of the room.

(WTOP/Jessica Kronzer)

6/10

6/10

A group of four rehearses choreography ahead of their performance, ‘Carmina Burana & More!’ where two dancers are suspended upside down by their partners with their heads toward the floor. In the pairing closest to the camera, Hannah Locke is held up by choreographer Ahmed Nabil.

(WTOP/Jessica Kronzer)

‘Resilience’: what it takes to be a dancer

Even with passion for the job, dancing comes with its own unique set of challenges. For starters, the market is competitive and women sometimes have more trouble finding jobs than men because they far outnumber male dancers.

“Men are in much higher demand because we need them to lift us and we need them to partner,” said Hannah Locke, 32, who’s dancing in the upcoming production.

The stress doesn’t end with being lucky enough to land a contract; balancing on the tips of your toes “takes a lot of resilience and pain and suffering,” she said.

“You have to go to extremes with your body and, at the same time, you have to pretend that it doesn’t hurt and it’s pleasant,” Moya said. “That whole emotional part of it is very exhausting, too.”

Sometimes people don’t understand that the woman-dominated field is full of athletes, she said. Moya, for example, includes strength training as part of her workout routine to help her dancing. Her personal record (PR) on the leg press is 400 pounds.

“I can move some weight, even though you see me as this tiny human,” Moya said.

That kind of exercise requires fuel to build muscle.

The idea that ballerinas are underfed to maintain their physique is something multiple dancers told WTOP is a myth — though they acknowledged the dancing community isn’t completely immune to unhealthy dieting culture.

“Yes, we eat, we need to because we will burn the calories,” Moya said.

Typically, dancers with the Manassas Ballet Theatre take classes and rehearse four days a week. “It’s really just a 20-hour week, although we accomplish everything pretty much as if it were a 40-hour week,” Grant Wolfe said.

After rehearsals end, many will teach dance classes or pickup other second jobs to make a living — including Locke who teaches at two dance studios.

“We try to have a life, but we are bunheads at heart,” Moya said.

But the women agree that the toughest judgment on ballerinas is often self-imposed.

“As I’ve gotten older, yes, I may be a little bit more sore than I used to be, or some things feel a little bit harder physically, but I feel like emotionally, I am less hard on myself,” said Locke, who has been dancing since childhood.

7/10

7/10

Two pairs of dancers move in unison as they learn choreography. Ahmed Nabil (on the right) teaches the group his choreography with the help of his partner, Hannah Locke.

(WTOP/Jessica Kronzer)

8/10

8/10

Moya prepares to shift her weight from her left foot toward her right to relevé.

(WTOP/Jessica Kronzer)

9/10

9/10

Moya leaps through the air before landing gracefully onto the dance floor.

(WTOP/Jessica Kronzer)

For women who live for ballet, what comes next after they ‘retire’ from performing?

Grant Wolfe has been the company’s artistic director for around two decades but she continues taking dance classes, even after backing off from performing publicly.

She hasn’t performed someone else’s choreography in 15 years. That stint ends this weekend, though.

The ballet’s choreographer, Ahmed Nabil, asked her to dance in his piece.

“Are you crazy?” she replied.

Crazy or not, Grant Wolfe was dressed in costume when she spoke with WTOP: a navy dress with a billowy skirt to fit in on stage with her fellow dancers.

Like many athletes, Moya recognizes there will likely come a day when she isn’t able to make a career out of performing, but she said she’s not ready to retire yet. The company has hired her on as an outreach director in addition to signing her as a dancer.

“They are also giving me new opportunities … like a different career path that’s in line with what I love to do,” Moya said. “For when I’m not able to dance anymore.”

Moya said even once she stops dancing: “I will forever call myself a dancer.”

10/10

10/10

As loud booms echo from the speaker, two women are suspended in the air as their male dance partners hold them above their heads.

(WTOP/Jessica Kronzer)

Get breaking news and daily headlines delivered to your email inbox by signing up here.

© 2024 WTOP. All Rights Reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Jessica Kronzer

Jessica Kronzer graduated from James Madison University in May 2021 after studying media and politics. She enjoys covering politics, advocacy and compelling human-interest stories.