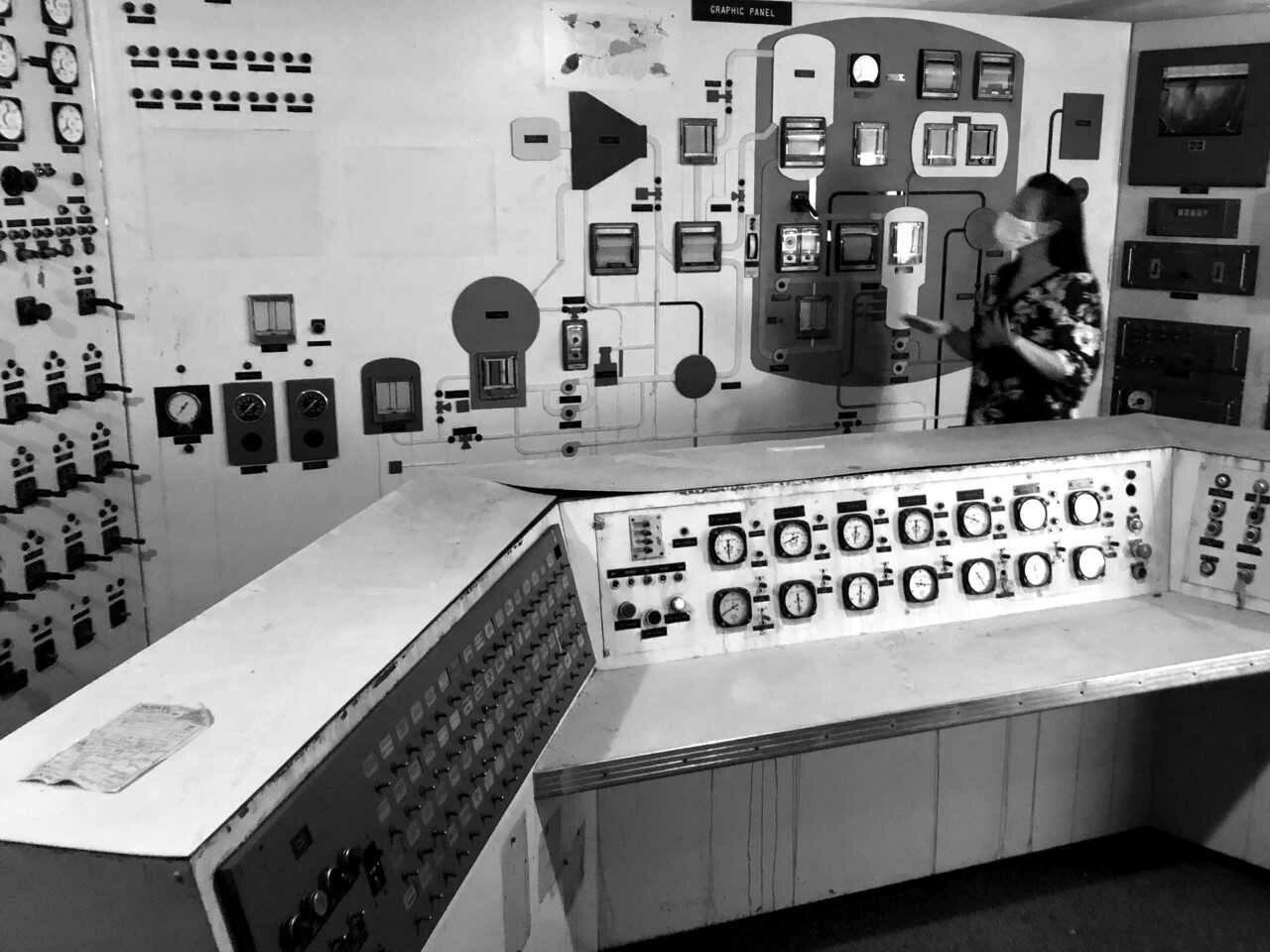

The red button was always there — just in case.

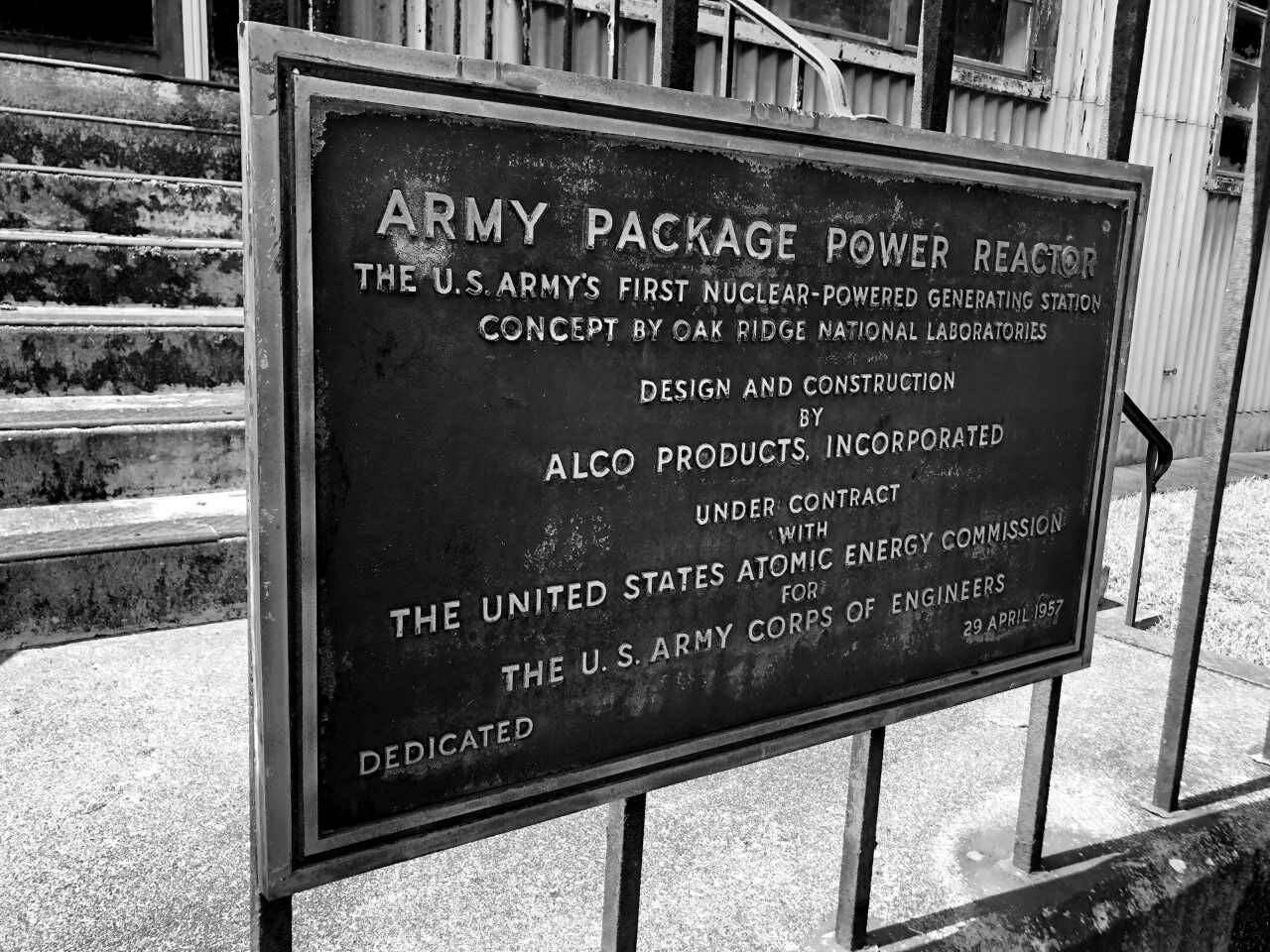

Most people never knew the United States’ first nuclear power reactor to provide sustained electricity to a commercial power grid was — and is — on the grounds of Fort Belvoir, the U.S. Army installation in Fairfax County, Virginia.

But it won’t be there much longer.

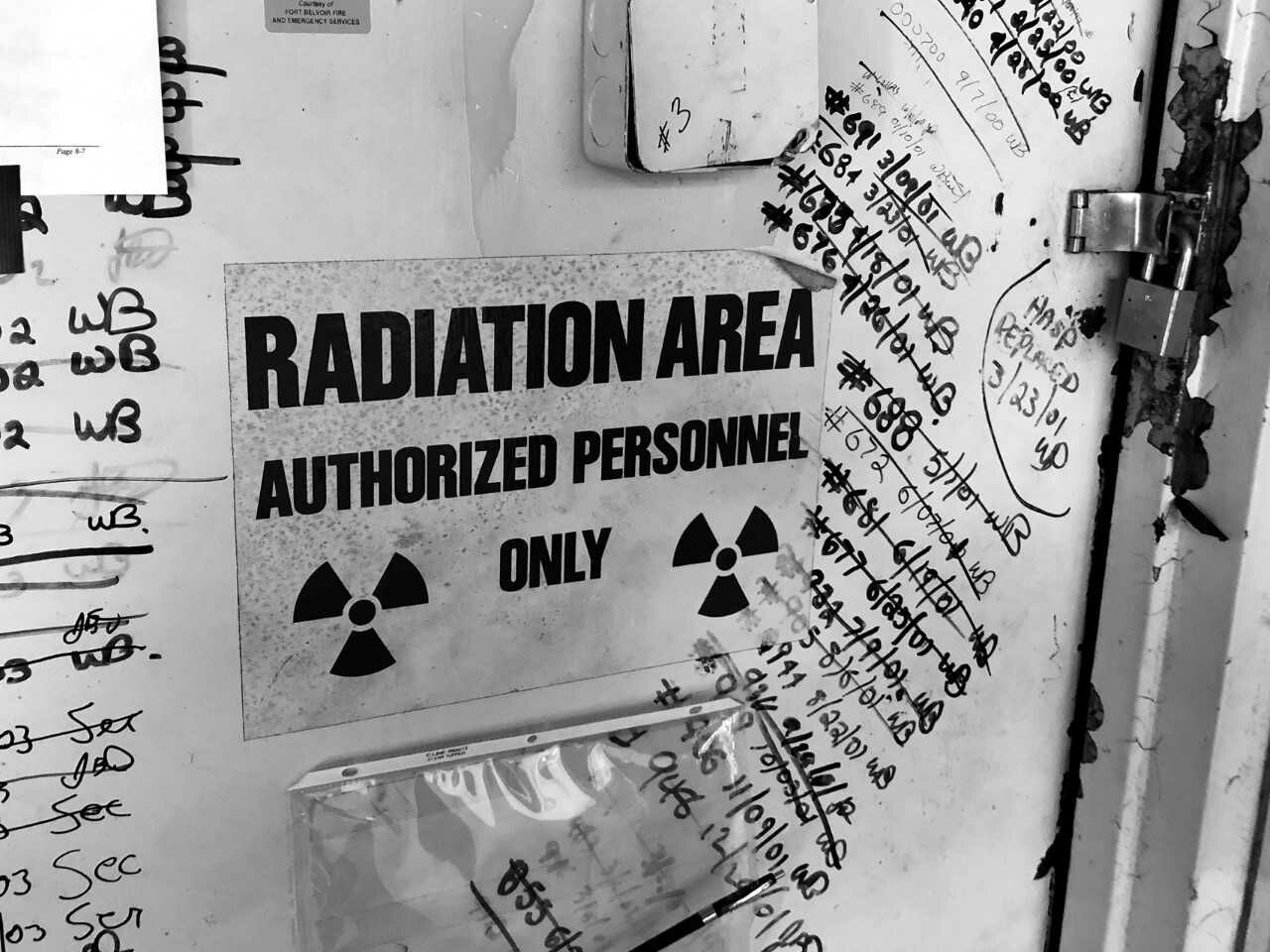

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers will soon dismantle the power plant, which generated electricity from 1957 until 1973, but it will have to be done carefully. The facility still has low levels of radioactivity in portions of the facility, despite being taken off line almost 50 years ago.

Thankfully, the red emergency shutdown button — labeled “manual scram” — was never needed.

Editor’s Note: This story has been updated to correct that it was thought to be the United States’ first nuclear power reactor, not the world’s.