30 memorable Palme d’Or winners as Cannes Film Festival kicks off

1946: Rome, Open City – Roberto Rossellini

After a hiatus for World War II, a great crop of films tied for the Palme d’Or in 1946, including “Rome, Open City.” Roberto Rossellini launched the Italian Neorealism movement by using non-actors, real locations and hidden cameras to film actual German soldiers during the Nazi occupation of Rome, winning at Cannes in the first of a trilogy with “Paisan” and “Germany, Year Zero.”

1946: Brief Encounter – David Lean

British master David Lean is best known for epics such as “Bridge on the River Kwai,” “Lawrence of Arabia” and “Doctor Zhivago,” but his most intimate film was this 1945 gem about a forbidden romance at a train station.

1946: The Lost Weekend – Billy Wilder

A year after his film noir masterpiece “Double Indemnity,” Billy Wilder delivered the screen’s greatest look at alcoholism casting Ray Milland for four days of boozing, withdrawal and hallucinations.

1949: The Third Man – Carol Reed

Arguably the best movie on this entire list, director Carol Reed crafted a film noir masterpiece for the ages as Joseph Cotten investigates the death of his friend (Orson Welles) in a Vienna-based mystery that takes us from Ferris wheels to sewer tunnels with a zither-based score. Filmmaking doesn’t get any better than this, folks.

1953: The Wages of Fear – Henri Georges Clouzot

William Friedkin’s “Sorcerer” and Netflix’s “The Ice Road” are just several of the films inspired by Clouzot’s masterpiece about four men hired to transport an explosive nitroglycerine shipment across rugged terrain in South America.

1955: Marty – Delbert Mann

Long before “Network,” Paddy Chayefsky penned arguably the most succinctly sweet romance of all time between a middle-aged butcher (Ernest Borgnine) and a school teacher (Betsy Blair) that was way ahead of its time in avoiding the pitfalls of toxic masculinity.

1959: Black Orpheus – Marcel Camus

This cinematic retelling of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth is set during the Rio de Janeiro festival of Carnival where country girl Eurydice (Marpessa Dawn) flees her home to stay with her cousin in the big city, where she falls for engaged tram conductor Orfeu (Breno Mello).

1960: La Dolce Vita – Federico Fellini

After the intimate masterpieces “La Strada” and “Night of Cabiria,” Fellini widened his scope to dissect French society, following Marcello Mastroianni’s philandering tabloid journalist wandering around Rome in a film that invented the term “paparazzi.”

1961: Viridiana – Luis Bunuel

Between his early masterpieces (“Un Chien Andalou” and “L’Age d’Or”) and later (“The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie” and “That Obscure Object of Desire”), Spanish master Luis Bunuel explored a young nun about to take her final vows in a surreal film most famous for its dinner table scene replicating The Last Supper.

1963: The Leopard – Luchino Visconti

Visconti’s “The Leopard” remains one of the most aesthetically beautiful movies ever made, starring Burt Lancaster as a noble aristocrat who tries to preserve his family and status amid the tumultuous social upheavals of 1860s Sicily.

1964: The Umbrellas of Cherbourg – Jacques Demy

It’s safe to say there would be no “La La Land” without “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg,” as Damien Chazelle’s Hollywood heartbreak finale is a direct homage to Jacques Demy’s colorful French musical masterpiece that stands the test of time.

1966: A Man and a Woman – Claude Lelouch

It’s rare for an international film to win Academy Awards for both Best Foreign Language Film and Best Original Screenplay, but that’s the glory of “A Man and a Woman,” following a widow and a widower who reluctantly fall in love as they bind the wounds of past tragedies.

1967: Blow-Up – Michelangelo Antonioni

Thirteen years after Alfred Hitchcock’s “Rear Window,” Michelangelo Antonioni created a voyeuristic mystery about a fashion photographer who captures a death on film, inspiring “The Conversation,” “Blow Out” and even “Austin Powers.”

1970: M*A*S*H – Robert Altman

Before the hit TV series became the most-watched finale ever, the film version of “M*A*S*H” delivered a black comedy set in the Korean War with Robert Altman’s signature style of multiple characters talking over each other — and even a nod to Bunuel’s “Viridiana” by replicating The Last Supper with war surgeons.

1974: The Conversation – Francis Ford Coppola

In between his two Best Picture winners — “The Godfather” and “The Godfather: Part II” — Francis Ford Coppola cast Gene Hackman as a paranoid surveillance expert who suspects that the couple he is spying on will be murdered. Gene Hackman later loosely reprised the role in Tony Scott’s “Enemy of the State.”

1976: Taxi Driver – Martin Scorsese

After his breakthrough crime flick “Mean Streets,” Martin Scorsese reunited with Robert DeNiro as a New York City taxi driver whose loner isolation plunges him into madness, political assassination attempts and ultimately vigilante heroism — all set to Bernard Herrman’s jazzy final score.

You talkin’ to me?

1979: Apocalypse Now – Francis Ford Coppola

Coppola adapted Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness” into an anti-war treatise on the Vietnam War, opening with “The End” by The Doors and the sounds of helicopter blades over Saigon ceiling fans. We the viewer lose our minds the further we get down river, as Martin Sheen crosses paths with Robert Duvall’s Col. Kilgore (“I love the smell of napalm in the morning”) and Marlon Brando’s insane Col. Kurtz (“The horror”). The documentary “Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse” recounts the hellacious backstory of this doomed production.

1979: The Tin Drum – Volker Schlöndorff

In one of cinema’s most clever allegories, Oskar Matzerath (David Bennent) is born in the Free City of Danzig, but falls down a flight of stairs and stops growing at age 3. When World War II breaks out in 1939, he symbolically plays his tin drum to protest against the people around him who are complicit with Nazi Germany.

1980: All That Jazz – Bob Fosse

“It’s showtime, folks!” Based on Bob Fosse’s own stressful attempt to stage “Chicago” and film “Cabaret” simultaneously, Roy Scheider is mesmerizing as the pill-popping, womanizing, near-death artist, who opens with a catchy “On Broadway” audition and ends in a body bag to Ethel Merman’s “There’s No Business Like Show Business.”

1984: Paris, Texas – Wim Wenders

In one of the best movies you’ll ever see — and I mean EVER see — Harry Dean Stanton shines as a drifter who wanders out of the desert after four years to reconnect with society, building to one of the greatest finales in cinema with his ex-wife through a two-way mirror. I can’t sing enough praises for this masterpiece.

1989: Sex, Lies & Videotape – Steven Soderbergh

Steven Soderbergh (“Traffic,” “Erin Brokovich”) launched his prolific career with this indie gem that defined the early Sundance era by exploring a sexually repressed woman whose husband is having an affair with her sister amid the arrival of a stranger with an unusual VHS fetish.

1991: Barton Fink – Coen Brothers

“The Big Lebowski” is the Coen Brothers’ comedy masterpiece; “No Country for Old Men” is their drama masterpiece, and “Fargo” is their best combination of both. Yet, “Barton Fink” won them the Palme d’Or, starring John Turturro as a renowned New York playwright who holes himself up in a California hotel room to write a screenplay, discovering the hellish truth of Hollywood thanks to John Goodman.

1993: Farewell My Concubine – Chen Kaige

Along with Yimou Zhang’s “Raise the Red Lantern,” Kaige Chen’s “Farewell My Concubine” is the most important Chinese film of the ’90s, following two boys who meet at an opera training school in Peking in 1924, forging a friendship that spans nearly 70 years through some of the most tumultuous events in China’s history.

1993: The Piano – Jane Campion

Jane Campion became the first-ever female director to win the Palme d’Or in this tale of a mute Scottish woman (an Oscar-winning Holly Hunter) who travels to a remote part of New Zealand with her young daughter (an Oscar-winning Anna Paquin in her debut) after her arranged marriage to a frontiersman (Sam Neill) before falling for his friend (Harvey Keitel) in a complex love triangle.

1994: Pulp Fiction – Quentin Tarantino

Boasting a quotable string of badass dialogue, an inventive fractured narrative presented out of order, countless genre homages and a killer soundtrack, Quentin Tarantino influenced filmmaking for the next 25 years with his “Royal with Cheese” banter, Jack Rabbit Slims dance-offs that turn into adrenaline shots to the heart, basement escapes from The Gimp, and The Wolf cleaning brains out of car.

1996: Secrets & Lies – Mike Leigh

British master Mike Leigh delivered one of the best family dramas of all time by following a Black woman (Marianna Jean-Baptiste) who reconnects with her white birth mother (Brenda Blethyn), building to a climactic birthday party sequence that remains a master class of ensemble casting and slow disclosure of backstory.

2003: Elephant – Gus Van Sant

Six years after his Oscar-winning gem “Good Will Hunting,” Gus Van Sant directed this long-single-take masterpiece set in the halls of the fictional Watt High School in the suburbs of Portland, Oregon. But there’s an elephant in the room: a school shooting awaits for a searing commentary on the Columbine High School massacre.

2011: The Tree of Life – Terrence Malick

Decades after “Badlands,” “Days of Heaven” and “The Thin Red Line,” Terrence Malick delivered the most thematically ambitious film since Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” by intercutting 1950s American suburbia with the formation of the universe (the 20-minute “creation” sequence won’t be for everyone). I hate to admit it, but it’s the last Malick film I actually liked.

2012: Amour – Michael Haneke

After winning the Palme d’Or three years before for “The White Ribbon,” Michael Haneke cast screen legends Jean-Louis Trintignant (“The Conformist”) and Emmanuelle Riva (“Hiroshima Mon Amour”) as an aging couple who embody the marriage vow of “in sickness and in health.” It’s devastating to watch but impossible to forget, winning the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film.

2019: Parasite – Bong Joon-ho

After sci-fi gems such as “The Host,” “Snowpiercer” and “Okja,” Bong Joon-ho made Oscar history by becoming the first foreign-language film to win Best Picture in this thrillingly unpredictable social commentary on class divides in South Korea. It remains one of the few films to win both the Palme d’Or and the Best Picture Oscar, proving its all-too-rare balance of artistic mastery and popcorn thrills.

WTOP's Jason Fraley salutes Palme d'Or champs (Part 2)

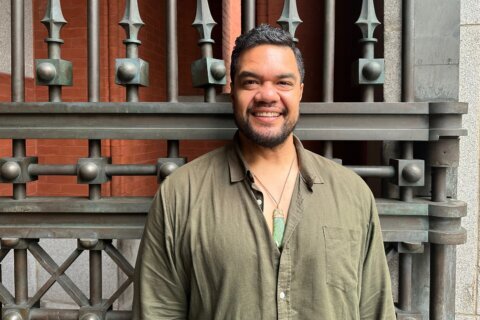

Jason Fraley

Hailed by The Washington Post for “his savantlike ability to name every Best Picture winner in history," Jason Fraley began at WTOP as Morning Drive Writer in 2008, film critic in 2011 and Entertainment Editor in 2014, providing daily arts coverage on-air and online.