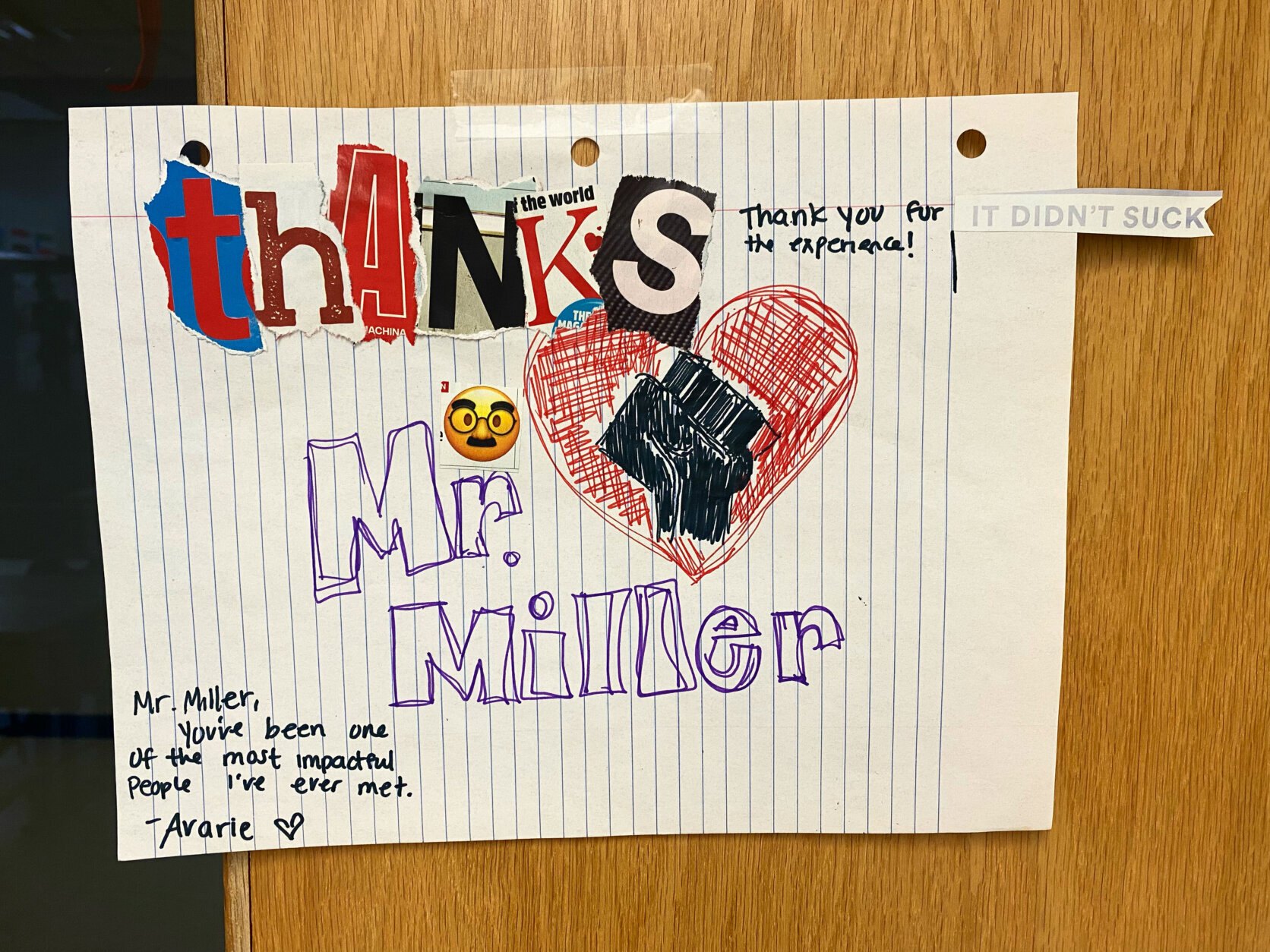

Even when students at South County High School in Lorton, Virginia, aren’t in Sean Miller’s class, they’re still buzzing about the day’s lesson.

On Thursday, a student approached Miller and expressed interest in signing up for his class next year. The student plans to do everything possible to add it to the schedule.

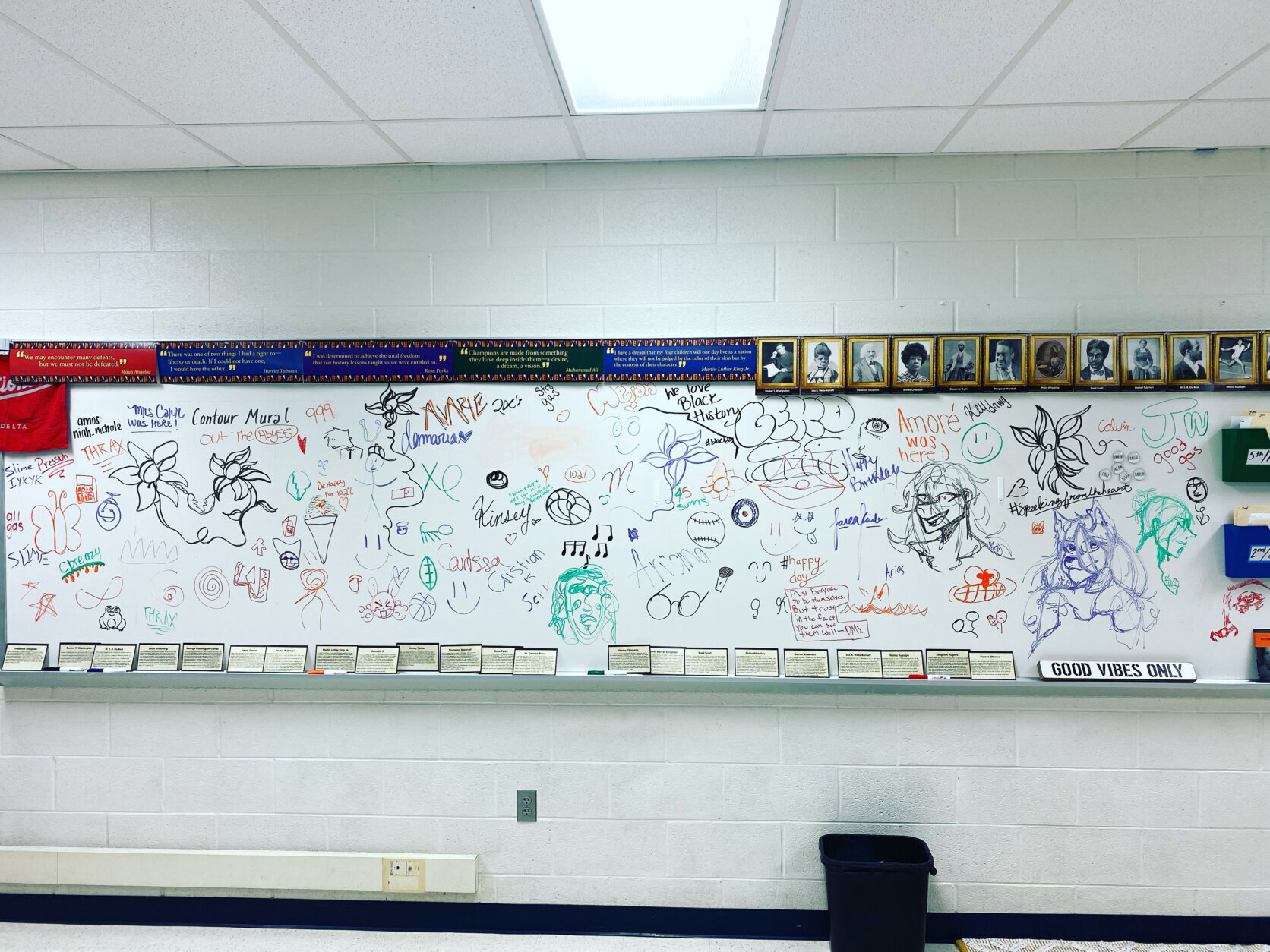

Students who aren’t taking one of Miller’s classes, though, don’t miss out. He opens his door to all students who want to contribute to a mural on a whiteboard. Some draw cartoons, illustrate historical figures or write messages to peers.

At the end of the grading period, he erases it so students can start over. It’s a space for students to be creative, he said.

Miller, who was recognized as the 2021 History Teacher of the Year by George Washington’s Mount Vernon, helped craft Fairfax County Public Schools’ African American History elective. With his first year teaching the course coming to an end, Miller’s desire to give students creative freedom has his colleagues and students talking.

“What keeps me going daily is just knowing that this is all about the students, it’s really not about me,” Miller said. “It’s not about my ego. It’s not about my accolades. It’s about every single day, how I can be unforgettable for the students’ sake?'”

Miller is about to finish his eighth year teaching at South County, but he started his professional career in marketing. He was part of a team that visited schools to craft marketing and operations plans, but after seeing Miller’s enthusiasm, his colleagues remarked that he would likely become a teacher.

He was inspired by his former art teacher, who was the first person to tell Miller he was too hard on himself as a student. He also uses some strategies introduced by one of his history teachers, such a game called “trash ball,” in which students can score points for answering questions about history. He often reflects on how fun that class was.

Now in the front of the classroom, Miller said he enjoys teaching history, because he can help students compare things that happened in the past with current events. He aspires to empower students to “see their capacity to make history.”

He enables students to express themselves using the arts — in one case, students were given the option of creating a song about African American history and their own experiences. Some students stop by after school to collaborate on the songwriting process.

Other students have opted to write a poetry book, and some are shooting short films or documentaries on different historical topics, Miller said. One student is working on an extended play that depicts the course’s core concepts, such as the ideas of power, society, culture, innovation, resistance and memory.

“I also tap into what interests the students, so not just putting them in a box to say, ‘OK, your project has to be this,'” Miller said. “I really want them to think about what would get them energized to talk about history, and then kind of leverage that to allow them to express themselves as best possible.”

In the last two years, Miller said, the class has discussed issues of social unrest. One class last week talked about the death of George Floyd, and drew parallels between Floyd and Emmett Till’s murders.

“My goal was always to say, ‘OK, it happened a long time ago, but a lot of mistakes are still happening now,'” Miller said. “And they also have some things that will happen in the future because of these past events. History is extremely important for me, because history’s happening every single day.”

One of Miller’s former students, who was a senior at the time, told him at the end of the year that if it wasn’t for his history class, she would have dropped out of high school. The ability to connect with students drives Miller, he said. And if hallway conversations are any indication, his students feel similarly.

“There’s going to be days where I feel like students may not even capture what I’m teaching with history,” Miller said. “But did I give them a life lesson that’s going to go beyond the content knowledge?”