The Mason Neck area in Virginia is an oasis of greenery amid nearby U.S. Route 1, Interstate 95, and the cities of Springfield, Lorton and Alexandria in Fairfax County, and Woodbridge in Prince William County.

In addition to the marshes and wetlands, Mason Neck has large mature trees. It’s a perfect place for eagles. The water has plenty of fish, and the eagles can perch on the tall trees and get a great vantage point.

“These sites are preferable for nests, along with the fact that they are near water, making fish easily accessible,” said Carina Velazquez-Mondragon, visitor services manager at the Potomac River National Wildlife Complex.

At least 50 eagles were spotted in the last aerial survey in 2021, the Potomac River National Wildlife Refuge Complex said in a statement.

That’s because Mason Neck is a National Wildlife Refuge, established in 1969 — the first national wildlife refuge created specifically for the protection of bald eagles. As part of Women’s History Month, WTOP explores the story of the Fairfax County woman who fought to keep the refuge in its pristine natural state.

“The bald eagles that have come back, and the clean water that we have in the Potomac River now, came back because of my mom … (and) other people that she engaged to get involved,” said Rob Hartwell, the son of Elizabeth Hartwell for whom the refuge was renamed in 2006.

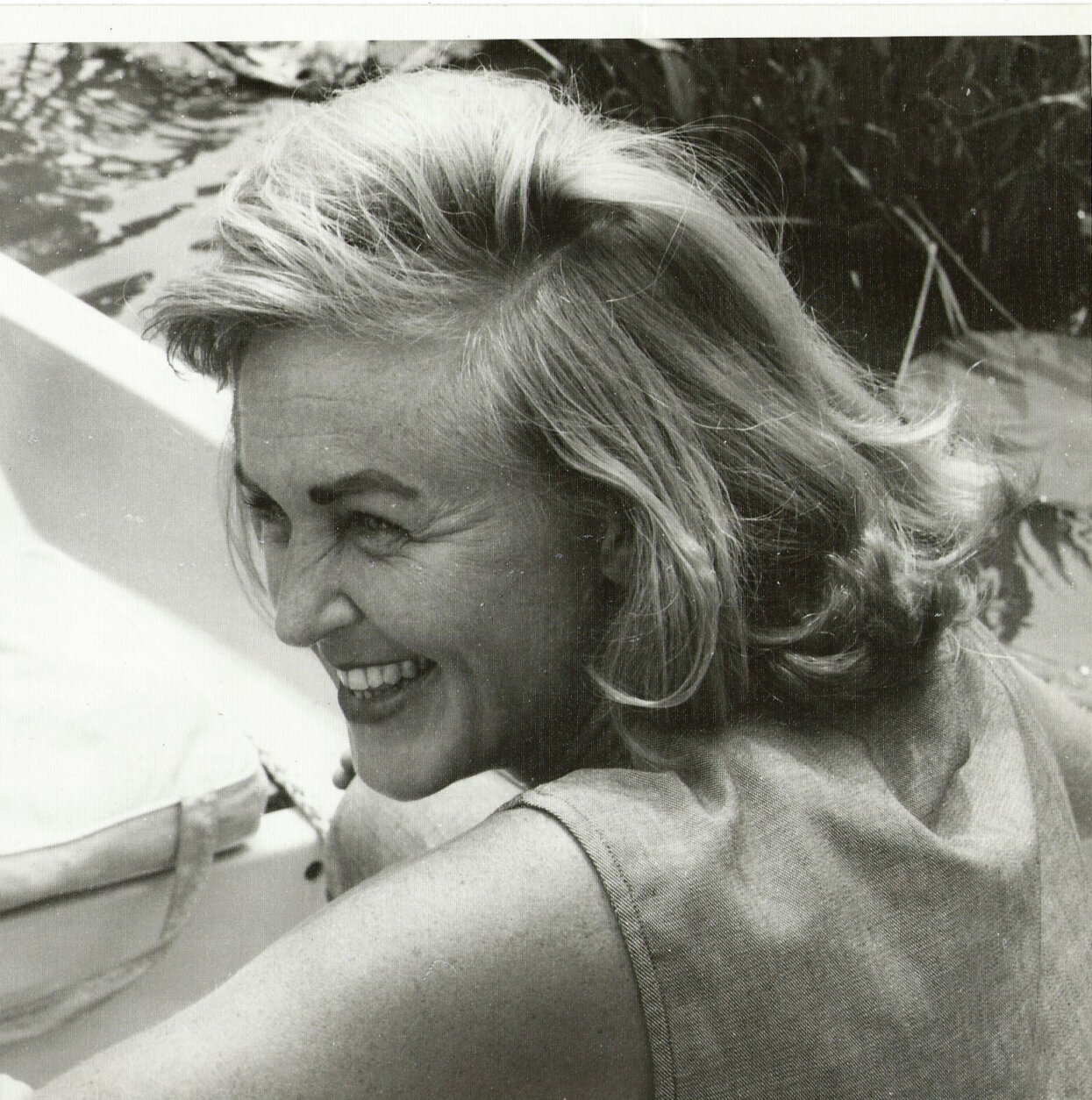

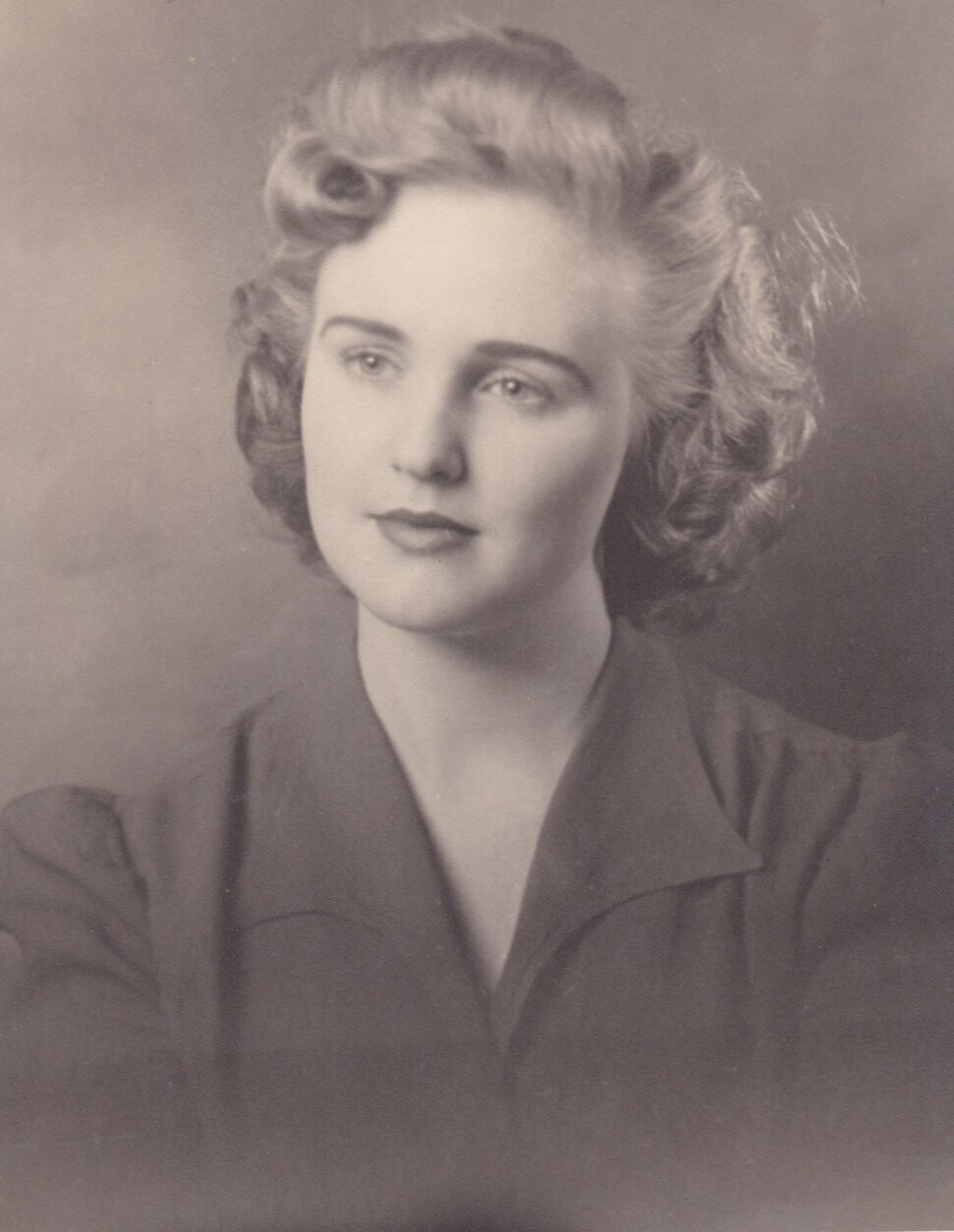

In the 1960s, Elizabeth Hartwell was a suburban housewife — an officer for the Hallowing Point Garden Club, who “took great pride in flower arranging,” according to Elizabeth Rieben in her master’s thesis about Hartwell’s work protecting the Mason Neck area.

But she was also a resourceful and tenacious woman, who was passionate about stewardship and preserving the environment and the wildlife surrounding her Fairfax County home.

She died in 2000 at 76, and six years later the refuge she fought to preserve was approved by Congress to be renamed the Elizabeth Hartwell Mason Neck National Wildlife Refuge.

The refuge is also the home of Virginia’s largest great blue heron breeding colonies, as well as birds, deer, groundhogs and wood ducks. It provides a healthy, undisturbed habitat suitable for many species of wildlife and plants, Velazquez-Mondragon said.

“In an area surrounded by so much development, Mason Neck is a quiet, natural place for migrating birds to find an area to rest and eat without being disrupted by vehicles, pets and people,” Velazquez-Mondragon said. Much of the area is closed to human disturbance, giving the wildlife plenty of room to roam.

‘Eagle Lady’ flies in the face of ‘Kings Landing’

The growth around the Mason Neck area was already well underway in the 1960s. There were plans to create a satellite city in Mason Neck to be called Kings Landing. This development would have included a planned community, a deep-sea port, gas pipelines and an airport. It was tagged as a “Living Williamsburg,” a “model colonial city” with homes, a golf course, a marina and stores, Rieben wrote.

Hartwell caught wind of the planned development, and she used the country’s symbol to sway people to her side.

In the mid-1900s, bald eagles were in danger of extinction due to habitat destruction and degradation, illegal shooting and contamination of its food source, largely as a consequence of the pesticide DDT, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

By 1963, there were only 417 nesting pairs of bald eagles known to exist, and the species was in danger of extinction. But Elizabeth Hartwell counted more than 30 bald eagles that year in Mason Neck’s Great Marsh, emphasizing the importance of the peninsula to these large raptors, Rieben wrote.

“Mom thought the American bald eagle was a symbol for a nation, and we shouldn’t allow it to be eliminated, and the development come in and eliminate its habitat,” Rob Hartwell said.

His mother organized citizens and went about letting politicians know about Mason Neck and its significance. When he was about 9 years old, she would sometimes take him to Fairfax County Planning Commission meetings, where he said he would fall asleep a lot of the time.

But he does remember developers and county officials flapping their arms and making fun of his mother. They called her the “Eagle Lady,” Rob Hartwell said. But his mother would often come out victorious, and her detractors would leave in defeat with their heads down because “she beat them every time,” he said.

There was growing consciousness about the environment in the 1960s, especially after Rachel Carson’s book “Silent Spring,” which detailed the adverse effects of pesticides in the environment. Rob Hartwell said that his mother was devastated when she unknowingly used an insecticide containing DDT that led to the death of a nest of tanagers.

“Mom went from being a kind of a garden club housewife to (falling) passionately in love with the environment, with Mason Neck, with history, and the bald eagles,” Rob Hartwell said.

Elizabeth Hartwell and two other Virginia activists established the Mason Neck Conservation Committee in 1965. Its members conducted a strategic letter-writing and telephoning campaign to key leaders with the goal of encouraging state and federal attention to preserving the “recreational and wildlife values” of Mason Neck, Rieben wrote.

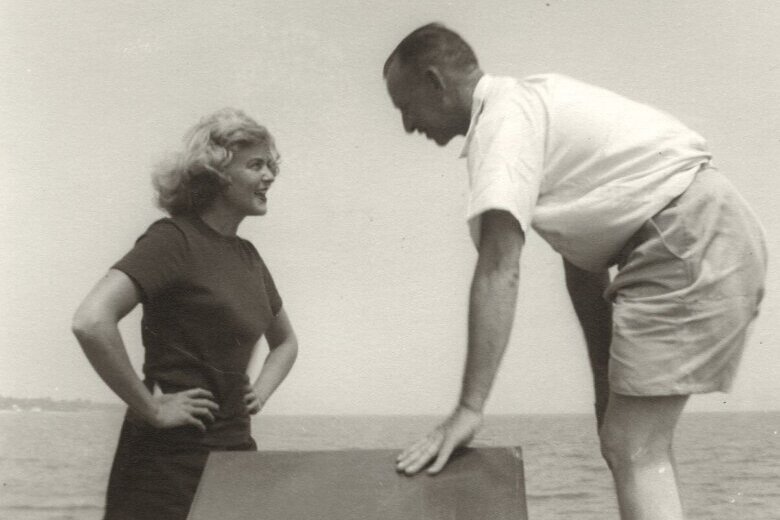

She also took politicians on her boat to see the eagles, often towing a canoe so they could access hard-to-reach areas.

“They were amazed. They didn’t know this kind of area existed in Fairfax County, and Fairfax was exploding in growth,” Rob Hartwell said.

One of the stories that he is going to include in a book he is writing involves the time his mother didn’t come home after taking three politicians in suits on a boat tour. The boat had broken down, and his mother walked in the door around midnight “exhausted, muddy, sweaty,” he said.

She walked three miles on the muddy bottom, stepping on snapping turtles and crabs, and swam when the water got over her head. None of the politicians took off their suit jackets or ties and got out of the boat to help her, Rob Hartwell said.

Her efforts led to more than 5,000 acres of land to be set aside for the public, which includes, in addition to the refuge that bears her name, Pohick Bay Regional Park, Potomac Shoreline Regional Parks, Mason Neck State Park and the Meadowood Recreation Area.

Elizabeth Hartwell remained devoted to preserving Mason Neck throughout her life, and she had a network of individuals that would tip her off on development plans that could affect the environment, whether they were proposals to dump D.C. trash in the Virginia marsh or the spraying of harmful aerosols in the area.

“She was able to pull together a coalition of people to preserve it from development. And thankfully, it is what it is today … probably the greenest place, as you are likely aware, in the whole Washington metro area,” Mason Neck Citizens Association Board Member Peter Weyland, said.

The Potomac River National Wildlife Refuge Complex said increasing storm frequency and intensity, rising temperatures, sea level rise, invasive plants and insects, pollution and litter, and an overabundance of white-tailed deer are some current issues facing Mason Neck. Erosion is also happening at a faster pace due to the rising frequency and intensity of storms.

From his mother, Rob Hartwell learned that one person can be heard and can make a difference, especially if that person knows his or her facts.

“She was crafty, too. She was smart. She used the American bald eagle as a symbol for why we should never develop the Mason Neck Peninsula,” Rob Hartwell said.

Following in the footsteps of Elizabeth Hartwell

There are simple things people can do to be stewards of the environment and follow in the footsteps of Elizabeth Hartwell, including properly disposing of trash and litter, so it does not end up in the waterway and wetlands.

And even if you don’t live near the refuge or any wildlife habitat, you can help by not planting invasive species, which can make their way into forests and wetlands and compete with native plants. Invasive species are any plant species or any sort of wildlife species not native to the area.

“Many invasives do not provide food for local wildlife and pollinators, making it difficult to stock up for long journeys and colder months,” Velazquez-Mondragon said.

And finally, you can volunteer at educational events, cleanups and habitat restoration projects. Velazquez-Mondragon said she’s hoping to welcome more volunteers to help with various projects, such as planting trees along the Potomac Heritage Trail, or staffing the front desk at the information center.

“What we have is precious; we can’t afford to lose it. If we ever allow it to be developed, It’s never going to go back to its natural state,” Rob Hartwell said.

Weyland said he believes Elizabeth Hartwell’s efforts were important in making residents of Fairfax County, including local politicians, realize that Mason Neck is a green space that deserves to be preserved. “Everybody recognizes that it’s a unique area. Lots of eagles, ospreys, fishing, boating, canoeing.”

Velazquez-Mondragon said that Mason Neck is really special.

“When you come flying in on a plane into Reagan National Airport, you can look down and specifically spot Mason Neck because there’s so much greenery,” Velazquez-Mondragon said. Meanwhile all around it are developments, houses and businesses; but not at Mason Neck. “It’s just green.”