Imagine waking up every day knowing your grandfather wrote cinema’s gold standard.

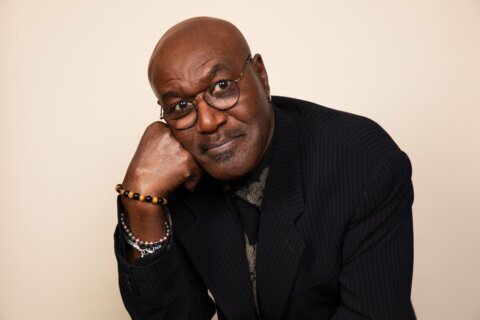

That’s the reality of D.C. native Ben Mankiewicz, host of Turner Classic Movies, whose grandfather Herman Mankiewicz penned the Oscar-winning script for “Citizen Kane” (1941), voted by the American Film Institute as the single greatest movie ever made.

This Friday, Netflix releases David Fincher’s nostalgic biopic “Mank,” a surefire Oscar contender starring Gary Oldman as Herman during the controversial writing of “Kane.”

“I got emotional when the title card came up like, ‘I can’t believe you’re making a movie about my grandfather,'” Mankiewicz told WTOP. “He was the highest-paid writer in Hollywood, then lost it all. … He was a drinker [and] sabotaged his career. … He hated that he was great at ‘popcorn frivolousness.’ … He should’ve been enormously proud.”

To be clear, “Mank” is not a film for casual moviegoers. Rather, it’s a black-and-white love note to cinephiles who appreciate the significance of “Citizen Kane,” both to cinema history and its enduring political commentary on egomaniacal media moguls.

“It was a big deal when it came out in 1941,” Mankiewicz said. “This was a character in Charles Foster Kane, who was very clearly modeled on William Randolph Hearst, who was as influential a publisher as there’s ever been in American history. … Hearst tried to stop it throughout his minions … who he paid off and tried to stop the movie.”

Adding to the allure was boy genius Orson Welles, fresh off the radio broadcast “War of the Worlds” (1938), convincing Americans that aliens were invading New Jersey.

“It was his first movie,” Mankiewicz said. “He came out to California at 24, got this unbelievable contract from RKO: ‘Make two movies. Do whatever you want. Produce, write, direct and star.’ That drew instant resentment from those who were established in Hollywood, not just directors, but everybody: ‘Why does this kid get this deal?'”

The result was groundbreaking, written as a fractured narrative long before “Pulp Fiction” (1994) and directed with a symbolic idea behind every single shot, such as characters growing or shrinking in size depending on their feelings of self-worth.

“It was brilliant,” Mankiewicz said. “Welles had all these deep-focus shots. … Then the narrative structure of it, which moved back and forth. … Welles had significant help from really talented professionals — my grandfather Herman Mankiewicz on the screenplay, Gregg Toland on the cinematography [and] Robert Wise in the editing.”

The film earned nine Academy Award nominations but infamously lost its Best Picture bid to John Ford’s “How Green Was My Valley” (1941). This was almost certainly due to Hearst’s defamation campaign.

“[Welles] was disappointed it didn’t win Best Picture or Best Director, but in a sense it’s better,” Mankiewicz said. “That’s part of the narrative of the making of the movie: that there was this movement to stop it and somehow ‘How Green Was My Valley’ wins Best Picture. … It’s as silly as ‘Shakespeare in Love’ beating ‘Saving Private Ryan.'”

The film’s only Oscar win came for its screenplay, shared by Mankiewicz and Welles, sparking an ongoing debate over who deserved most of the credit. Film critic Pauline Kael defended Mankiewicz’s contributions in “Raising Kane” (1971), while colleague Peter Bogdanovich defended Welles’ contributions in “The Kane Mutiny” (1972).

“My grandfather is by far most responsible,” Mankiewicz said. “Welles did a tremendous job of condensing it, so you could argue he deserved half the credit, but my grandfather wrote the movie. … He did take $10,000 to keep his name off it, then realized he had written the only thing he was proud of and wanted his name on it.”

Similarly, Fincher leaves his name off the script for “Mank,” giving full credit to his late father Jack Fincher, who wrote the original draft back in the 1990s. Fincher structures his “Mank” script just like “Kane,” a spiral of puzzle pieces across various flashbacks.

It opens in 1940 with Herman breaking his leg in a car accident, causing Welles and producer John Houseman to put him up in a remote house away from Hollywood for three months to write the entire screenplay.

“Fincher does the movie in these flashbacks … bits and pieces of Herman’s life. He’s a superstar in ’31, then in ’34 and ’37, you see his disillusionment with Hollywood.”

Fincher also shines from a directing standpoint as he did in “Se7en” (1995), “Fight Club” (1999) and “The Social Network” (2010). In “Mank,” he shoots in black-and-white to evoke the time period, superimposing the script’s slug lines in a typewriter font.

“I think it really works,” Mankiewicz said. “Each scene starts with ‘EXT. MGM STUDIOS’ and the date and day [superimposed on screen]. … Fincher is this brilliantly talented, innovative, breakthrough director, one of the top directors working today.”

Like Vincente Minnelli’s “The Bad and the Beautiful” (1952), “Mank” is a feast for film buffs with depictions of titans like Louis B. Mayer, Irving Thalberg and Marion Davies.

“He nailed it,” Mankiewicz said. “He got classic Hollywood. He got Louis B. Mayer’s power, which was near absolute; Thalberg’s brilliance as the head of production at MGM; and the camaraderie among writers. I think they captured the importance of the writer. You even see the importance of the writer diminish over the course of the film.”

Indeed, the film shows Herman thriving on the ground floor of a booming industry.

“He brought all these great writers out to L.A.,” Mankiewicz said. “The famous telegram he sent to Ben Hecht, which was basically, ‘Get out here as soon as you can. There’s millions to be made. Everyone else is an idiot. Don’t let this get around.'”

Ironically, Herman’s son Frank went the opposite route, moving from Los Angeles to Washington D.C., where he became press secretary to Robert F. Kennedy, announcing his death to the country. He also served as the president of National Public Radio.

“My father was the smartest Mankiewicz,” Mankiewicz said. “He felt the same thing that his father felt: that Hollywood was not … a noble way to make a living. My dad was an entertainment lawyer for some cool clients, Steve McQueen and James Mason, but when Jack Kennedy was elected, he thought, ‘This is what you’re supposed to do.'”

What was it like growing up with a famous father in the nation’s capital?

“We’d go to the supermarket every Saturday and inevitably people would come up to him,” Mankiewicz said. “My dad was a very influential guy for a long time in Democratic politics [with] tons of Republican friends. … He was always incredibly optimistic about the future of the country. … He would have had a very tough time the last four years.”

As for Ben, his first TV job came working alongside famous D.C. sportscasters.

“The first summer after my sophomore year, I worked at the ‘George Michael Sports Machine,’ then came back the next year and worked for Glenn Brenner,” Mankiewicz said. “I became a television reporter [and] came out to L.A. to audition for 138 jobs. … Then I landed the best one at TCM in Summer 2003. … It’s been a great 17 years.”

No matter what he accomplishes, he enjoys calling into his hometown radio station.

“It’s great to talk to you because if you asked me to name call letters from growing up in D.C., I just would have said, ‘WTOP,'” Mankiewicz said. “That’s just what you’d listen to for news when I was a kid throughout forever — and great call letters, too. I know there’s been a lot of changes in D.C. media, but it’s still fun to be talking to WTOP.”

Listen to our full conversation here.