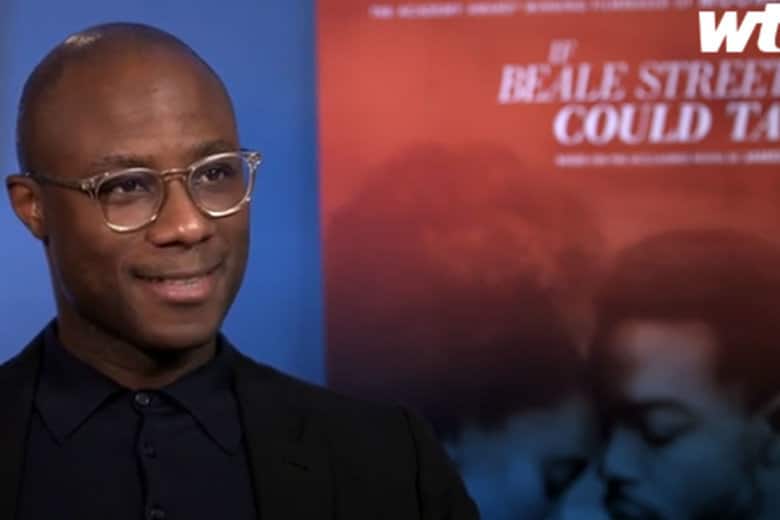

WASHINGTON — How do you follow-up on a Best Picture masterpiece like “Moonlight?”

If you’re Barry Jenkins, you direct “If Beale Street Could talk,” the first narrative adaptation of James Baldwin, who recently inspired the Ava DuVernay documentary “I Am Not Your Negro.”

Did Jenkins feel any pressure making “Beale Street” after his big Academy Award victory?

“I didn’t think of it that way: that you had to be selective coming off Best Picture,” Jenkins told WTOP. “I wrote this script the same time I wrote ‘Moonlight’ in Summer 2013. … I wrote the script before having the rights to the book, then in the process of making ‘Moonlight,’ got the rights from the estate. It was really nice once the Oscar season started to really know what the next piece was going to be … which I consider a companion piece to the previous film.”

Based on Baldwin’s powerful 1974 novel, “Beale Street” follows 19-year-old Tish Rivers (KiKi Layne), who is carrying her first child while scrambling to prove the innocence of her fiancé Alonzo “Fonny” Hunt (Stephan James), who is falsely accused of rape in 1970s Harlem.

“I read the book for the first time in 2008,” Jenkins said. “A friend sent it to me … Everyone knew I was a fan of Baldwin’s work, but I actually hadn’t read this one. I read it and was really surprised how romantic, how lush the love between these two characters. They’re essentially soulmates, but still how Baldwin, through his cultural critique, his views of society, managed to make this very persuasive argument of the brokenness of the American justice system.”

Beneath the larger social commentary lies a deeply human story of a young couple trying to make it amid insurmountable odds, portrayed with grit by Layne in her debut feature film.

“I saw ‘Moonlight’ when it hit theaters in Chicago — Ashton Sanders is a friend of mine, so I was like, ‘I gotta go support Ashton’ — and I was just blown away,” Layne told WTOP. “I remember the credits rolling and just sitting there, me and my friend, like, ‘What did we just see? That is unlike anything we’ve ever seen before.’ Then hearing this was his follow-up, Barry Jenkins and James Baldwin, I knew this was going to be something extremely special.”

Her co-star is the very talented Stephan James, who played Jesse Owens in “Race” (2016).

“He has this really great confidence about him that was really nice to tap into,” Layne said. “I’m coming in a little unsure of myself like, ‘What am I doing on this set? What does he mean setting up this shot like this? What is this?’ But Steph really encouraged me to take ownership of my place on that set, my place in the film, and I’m so, so thankful for that. He’s also just really fun to work with and really patient and respectful of me being on this learning journey.”

Related Story: ‘Race’ recounts the time Jesse Owens left Hitler in the dust

Guiding both rising stars is veteran actress Regina King (“Boyz N the Hood,” “Jerry Maguire”), who just earned a Golden Globe nomination for her role as Tish’s mother Sharon. You must see “Beale Street” alone for King’s harrowing scene breaking down in Puerto Rico while trying to convince the rape victim that Fonny didn’t do it. It’s the clip they should play on Oscar night.

“She’s just so natural,” Layne said. “You can tell that she’s someone who really just receives everything so beautifully. Watching everything that she was doing in Puerto Rico, that’s what I was taking away: I’m watching someone who really knows how to receive and listen and be affected in the moment by what her [screen] partners are giving her.”

For all the heavy moments, there’s an equal amount of charm, particularly when Fonny shows Tish their future SoHo apartment. The camera swoops around the empty room as Fonny imagines carrying an invisible fridge, table and stove with his Jewish landlord (Dave Franco).

“The loft itself, as we were going around it, I just thought, ‘This doesn’t make any sense. You can’t make this into a home,'” Jenkins said. “Then it clicked: What’s a testament to love and faith than someone promising you something that’s impossible and you going, ‘OK, I believe you.’ So, I rewrote the scene to reflect this thing where they’re pretending to grab the fridge.”

It’s an absolutely adorable interplay between the actors, showing their true human touch.

“That was a fun day on set,” Layne said. “We were having a good time just playing with each other. Barry creates such a great environment … to feel comfortable being open, playing, giving, receiving. That scene is definitely one of those moments where you see us having fun.”

It builds to a touching rooftop scene between Fonny and the landlord.

“I was trying to find some connective tissue between he and Fonny,” Jenkins said. “That’s when we added the line where Fonny’s like, ‘Yo, Mr. White Man, why the hell are you giving us this loft? … Nobody’s going to sell a loft to two negros.’ I thought: everybody has a mother. That’s the only thing that makes the difference between us and them. You think ‘us and them’ is black and white, but really it’s people who have been loved and have been nurtured and therefore they have a very open heart, and people who maybe haven’t had that opportunity.”

The apartment single-take is just one of many fascinating directing techniques by Jenkins, including voiceover freeze frames like “GoodFellas,” a slow-motion circling shot around an art sculpture in a smoke-filled room and witnessing childbirth from the newborn’s point of view.

“Myself and the cinematographer were talking about this idea of how to end the film, because the language at the end of the book is very soft, it’s not concrete imagery,” Jenkis said. “This woman is carrying this child the entire film; I wanted to be a part of the birth … It’s a very elevated, not documentary, depiction of birth. Because of all the things these characters are carrying over the course of the film, it felt like something visually spectacular was earned.”

It’s a dazzling reminder of how cinematic language transcends other mediums.

“It’s not literature; it’s cinema,” Jenkins said. “It’s not worth telling these stories if you don’t create an immersive experience for the audience. As I say, ‘Walk ’em loud in the character’s shoes.’ … I do feel like the auditorium of a cinema is like a virtual reality headset. The image is always in front of you and the sound is all around you. So, I’m really trying to always find ways to do things with the form and with the actual aesthetics to heighten the experience.”

It’s the same daring approach as “Moonlight,” which featured a symbolic use of the color blue.

Related Story: Oscar lunar eclipse: What makes ‘Moonlight’ Best Picture worthy?

“Some of the things we did with color in ‘Moonlight,’ we did in a softer way in this film,” Jenkins said. “Myself, the D.P., the costume designer, the production designer, we’d all get together and drink wine over the course of pre-pro and pass this color around, pass this image around. Eventually you start to see these things pop up in everybody’s department. What’s happening is we’re all just getting inside this young woman’s head and trying to use everything at our disposal — the clothes, the lenses, the quality of light — to reflect what it’s like to be her.”

For all this, another Best Director nomination is likely on the horizon, where he may compete against “First Man” director Damien Chazelle, who beat him for Best Director in 2017. The two are linked after “La La Land” mistakenly won Best Picture, before the correct winner was announced to be “Moonlight” in a now infamous Oscar gaffe with the wrong envelopes.

“I didn’t want to say anything in the moment,” Jenkins said. “The thing with Damien is we were both at Toronto, which is where this film world premiered. I go into this suite, sitting ready to do this interview, and I look at the monitor at who’s doing the interview before me and it’s Damien! He came off from backstage, we looked at each other, we looked around and went to give each other a hug — and we knew everybody’s phone was out taking all of these photos.”

Today, he smiles at the way that fate has etched them together in Hollywood history.

“In a way, it’s kind of lovely,” Jenkins said. “Those two films are very different, ‘La La Land’ and ‘Moonlight,’ and these two films are very different, ‘First Man’ and ‘Beale Street,’ but I think we both go about it the same way. It’s really cool that for whatever crazy reason these two storytellers are somehow always linked.”

Watch our video with Jenkins at the top of the article. Watch our video with KiKi Layne below: