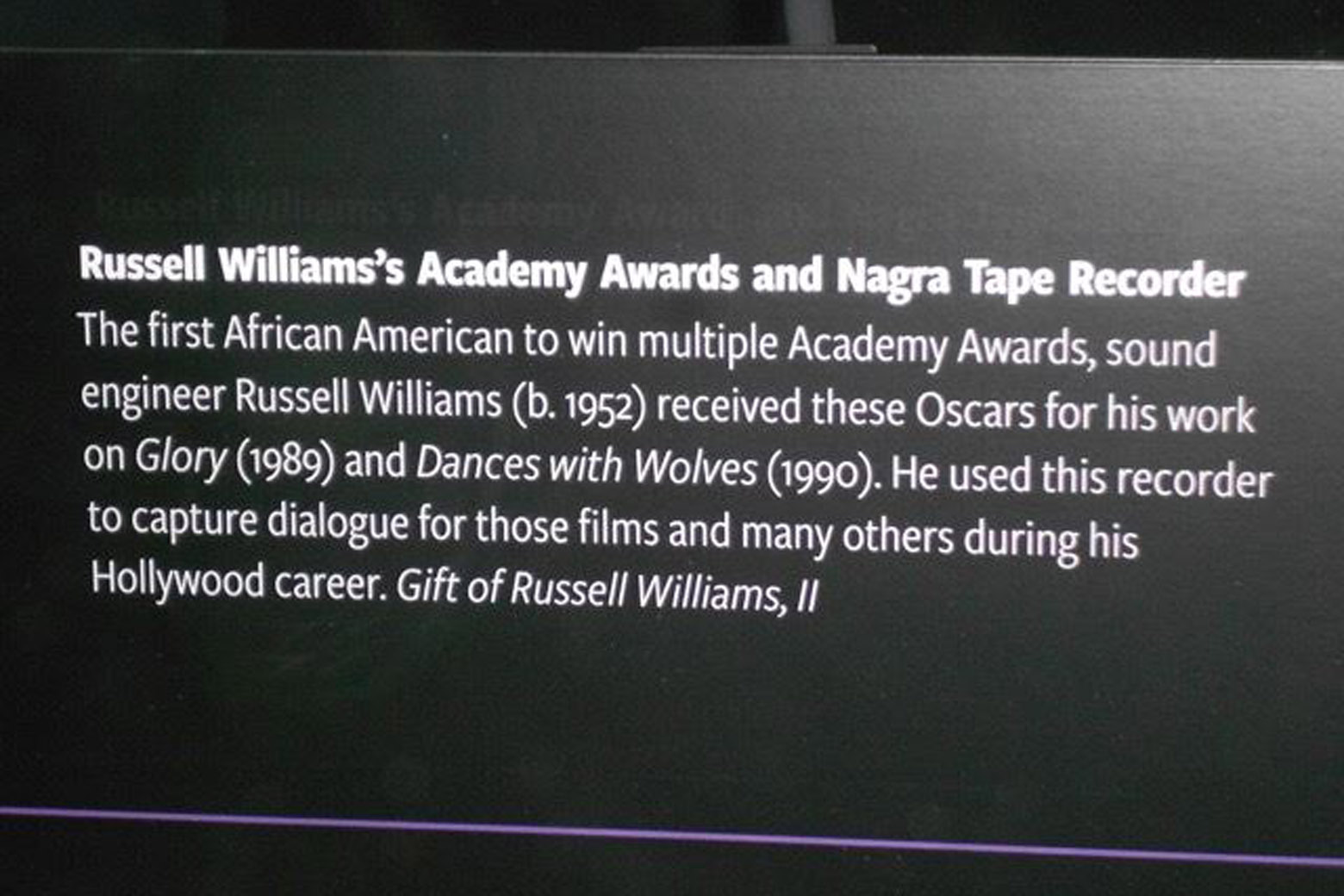

WASHINGTON — Who was the first African-American to win multiple Oscars? Was it the great Sidney Poitier? Denzel Washington? Spike Lee? Quincy Jones?

Nope, it was actually sound mixer Russell Williams, currently a professor at American University.

Now, Williams is donating both of his Oscars and his Nagra sound device to the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, which opens on the National Mall this weekend.

“I may not be the first African-American who deserves to be the first multiple winner, but I’ll take that distinction,” Williams humbly told WTOP. “I think partly because I worked behind camera. … If you’re an actor, it doesn’t matter ethnicity, people really do make a face-value judgment: You’re too tall, too old, that’s not the look. … But [with me] if you turn that button on and you heard Denzel, James Earl Jones or Kevin Costner and they didn’t sound like Mickey Mouse, I guess this person did their job.”

For Williams, parting with his prized Oscar possessions wasn’t that hard a decision.

“In terms of why I want to donate, I’m a D.C. native,” Williams said. “As a longtime admirer of the Smithsonian … rather than wait until maybe family members want one, let me just put these in the Smithsonian for safe keeping, and I know they’ll always be part of our national collection.”

Growing up in Southeast D.C., Williams remembers visiting the Smithsonian as a kid.

“I blame my mom and my dad,” Williams said. “One summer, my mom said, ‘We’re going to every building in Washington that has a tour.’ … I already had my summer planned out, I was gonna throw rocks at the girls and play softball! But as we did these tours and went into these great buildings and I saw all these exhibits, I never thought I would ever have anything to contribute to the Smithsonian.”

In addition to visiting museums, he’ll never forget seeing “In the Heat of the Night” (1967) as a teen.

“Not only were they so impressive on camera, but by that time I was listening to a lot of jazz and I said, ‘Wait a minute! Quincy Jones did the score?'” Williams said. “So the whole concept of an African-American working behind the camera was a revelation. … So it wasn’t an immediate, ‘Alright, I’ve got to go to Hollywood,’ but at least something tapped me on the shoulder, something to be continued.”

After graduating Woodrow Wilson High School in 1970, he went to college at American University.

“By the time I had changed my major in journalism to broadcast production … I decided to take some film classes because that was our tradition: Sunday school, Sunday dinner, then pick a movie. I didn’t realize how many films I had seen. … My love of film as a medium really was fostered at American.”

Around that time, he worked at NBC-4 as an engineer during the Watergate hearings and ABC-7 in the documentary unit under titan Paul Fine, whose son and daughter-in-law recently won Oscars.

“They opened the door for me,” Williams said. “I started working as the second documentary unit sound recordist. … Three weeks later we were in Rome and I said, ‘Ahh, OK. This is doable. Not only do I see the world, do what I love to do and somebody else picks up the tab?’ You can’t beat that!”

When a small indie film came to shoot in D.C., he stayed in touch with the crew, and after a year of saving up money, he hopped a TWA flight to the West Coast to try his hand at Hollywood in 1979.

“It took me seven years to get in the union and nine years to get on my first real feature film in the sense that it was a great script, great actors and a joy to work on,” Williams said. “That was a little movie called ‘Field of Dreams.’ You might have heard of it.”

As sound mixer, he’s responsible for the rustling of corn stalks, cracks of the bat and pops of the mitt, romanticizing America’s pastime. He even solved the mystery of, “If you build it, he will come,” claiming that it’s the voice of director Phil Alden Robinson.

“The only reason I know that is … there’s a photo of him looking up at this big Neumann microphone. I said, ‘Ahh, he’s not in there narrating an audio book.’ So he is the voice,” Williams revealed. “Many years ago I asked him and he wouldn’t cop to it, but a picture is worth a thousand words. I’m sorry, Phil!”

He still can’t believe he recorded James Earl Jones, Kevin Costner, Ray Liotta and Burt Lancaster.

“For me as a kid going to the movies with my parents, I couldn’t believe I’m sitting here recording Burt Lancaster,” Williams said of Moonlight Graham. “As old as he was, man, he still had that jaw, he still had that glint in his eye. I think that’s the only time I can remember where I teared up on set. … When he stepped over that base path to tend to Kevin’s daughter, I was sitting like, ‘Why am I misty eyed?'”

The tears continued to flow when Williams took his father to see the finished film.

“This was the first feature film that we actually had a chance to go see together that I worked on, and my dad said, ‘OK, now I know why you moved across country. I’m just honored,'” he said. “I thought that movie should have won everything it was nominated for. … To see guys crying in the theater!”

While “Field of Dreams” was nominated for Best Picture, Screenplay and Original Score, it walked away empty-handed at the Oscars due to the competitive crop of films confronting our racial past: Spike Lee’s “Do the Right Thing,” Bruce Beresford’s “Driving Miss Daisy” and Ed Zwick’s “Glory.”

The lattermost film starred Denzel Washington, Morgan Freeman and Matthew Broderick about the first all-black volunteer company fighting for their own freedom from slavery during the Civil War.

“By this time, I had worked on enough films to not only look at what the story says but now I’m looking for the ‘aggravation factor.’ So a Civil War movie means mostly exterior in Georgia, so that means … cold at night, probably rain. … Then the New York Sunday Times had a story about this Civil War movie … So I’m saying, ‘Wait a minute, the 54th Mass.?’ We’ve signed Morgan Freeman, hoping that Denzel will sign and I said, ‘Oh you mean that Civil War movie!’ I’ll pay them to be on this one.”

The period piece was rich in sound design, from the inspirational spiritual clapping chant (“Oh my lord, lord, lord, lord”) to the horrific cracking of the whip during Denzel’s Oscar-winning teardrop.

“The whip is all post-production,” Williams explained. “When he’s putting the whip on Denzel, that whip wasn’t even like newspaper hitting you, because you really don’t want to injure your actor. That was acting! … I was so far back [from the camera] I didn’t see that tear until I saw it on the big screen.”

“Glory” won three Oscars — Best Supporting Actor for Denzel Washington, Best Cinematography for Freddie Francis and Best Sound, which Williams shared with fellow sound department colleagues Donald O. Mitchell, Gregg Rudloff and Elliot Tyson. Williams says he will never forget Oscar night.

“Your heart, your whole respiratory system comes to a halt, then you hear that name, you realize that’s us, so there’s a sigh of relief, then we have to negotiate our way through the aisle,” he said. “We hadn’t prepared anything, so [Donald] got through his speech in 15 seconds, he looks over his left shoulder at me and says jump in there. … Once I looked at the tape, being a sound guy, I didn’t like that I was leaning over the microphone! I thought, ‘Dummy, if you ever get back, stand up straight.'”

That second chance came the very next year for “Dances With Wolves” (1990), when Williams again won for Best Sound, this time sharing the award with Jeffrey Perkins, Bill W. Benton and Gregory H. Watkins. The group had previously worked together on “Field of Dreams,” where Williams met Costner, who tapped his trusty sound department to return for his directorial debut in “Dances.”

“When Kevin gets this project he’s directing and starring in, he takes [crew] from all his other films,” he said. “He brought transportation from ‘Bull Durham,’ he brought sound from ‘Field of Dreams,’ script supervisor also from ‘Field of Dreams.’ … That’s loyalty, people who we had a good relationship with, because when you’re on your first project, you don’t want to remember a bunch of names.”

Ironically, Williams almost turned down the offer.

“I was just outside for five months on ‘Glory’ and now I’m gonna do another?” he said. “Here’s that aggravation factor again, long days, and I think we started in July, so the prairie is hot as heck in July. Then by the time we got to November, I was in full duster, Resistol hat, my first pair of cowboy boots.”

The adventure paid off as the frontier epic won seven Oscars, including Best Picture, by showing a different side to the Western genre, painting Native Americans as humans rather than villains.

“Even in pre-production in South Dakota, there was a lot of grumbling in the state about why is this movie going to highlight what the Native Americans did?” he said. “If you grew up watching westerns, the Native Americans were the enemy, universally. So this film really pointed out that [they] were already into conservation of resources. We’ll only kill what we’re going to eat or use for clothing or shelter … We’re not going to slaughter for slaughter’s sake. … To see them as humans, raising families and wanting the same thing for their kids and community as you would want for yours.”

After his double dose of Oscar gold, Williams rattled off a string of impressive credits: Spike Lee’s “Jungle Fever” (“Great crew, difficult shoot, not the most cooperative director”); Eddie Murphy’s “Boomerang” (“Eddie was on top of his game and we just had a lot of fun”); Antoine Fuqua’s “Training Day” (“For directors that came from music videos, Antoine was probably one of the most prepared”); and William Friedkin’s “Rules of Engagement” (“He’s the first one that invited me to the table read”).

But it wasn’t all movie success. Williams also won two Emmys for his TV work, first for mixing sound on “Terrorist on Trial: The United States vs. Salim Amaji” (1988) and again with Friedkin on TV’s “12 Angry Men” (1997). He was nominated a third time for the miniseries “The Temptations” (1998).

“I’ve been really fortunate that of the nominations I’ve had, I’ve only been disappointed once and that would have been for my third Emmy [nomination] for the ‘Temptations’ miniseries,” Williams said. “But you know? Hey baby, you can’t win them all. I’m glad to be able to be in the history books.”

As a former winner, Williams is an Academy member and an annual Oscar voter, speaking with gravitas on the recent #OscarsSoWhite debate. While he’d like to see greater diversity in filmmaking, he likes that the Academy is a hard group to become a part of — an honor to be earned over time.

“Think of how many people have had great sporting careers, but don’t end up in the Hall of Fame,” Williams said. “The Academy is essentially a Hall of Fame. … Its real role traditionally had been to keep people out until they had achieved a certain amount of professional and artistic status.”

However, he does think some recent changes might help level the playing field.

“I’m fairly sure we’re going to have a diverse group of nominees [this year],” Williams said. “Hopefully with the additional members, and they took the cap off how many members they can add per year, so that may help. I’m not sure about brooming out the older members. I’m not sure that’s the right way to go. … Who else has time to see all those films except those who are retired from active film work?”

He doesn’t think the problem is so much bigoted voters; by then, it’s too late in the game. The real key to diversity is in the financing phase, finding wider representation of what is made in the first place.

“Not everybody in the Academy can be a bigot,” he said. “Last year, you had more than 300 films eligible to be considered in all categories. Say those films had at least 10 actors, that’s 3,000 acting roles that have to be whittled down to 10 nominations. So just mathematically, it’s really hard to get nominated. … There’s always gonna be more disappointed than anointed. That’s just the math.”

On top of the math, there’s a general tendency for the Academy to make “safe” picks.

“Hitchcock doesn’t have an Oscar on his mantle. How’s that possible?” he said. “This is what I know about the Academy, regardless of ethnicity. … The Academy tends to always take the softer option. … The year that ‘Glory’ doesn’t even get a Best Picture nomination, it goes to ‘Driving Miss Daisy,’ both about race relations, but one group has bayonets in their hands, the other has a steering wheel.”

In the end, he remains optimistic despite the #OscarsSoWhite controversy.

“I see the arguments on both sides and I think it really comes down to you have to have a pretty mean horse to win in the end,” he said. “There’s probably a better system somewhere, but this is the system we have. So all I say is you’re not gonna get there unless you persevere — and you need a little luck.”

These days, Williams has his American University students practice their Oscar speeches in class, having rejoined AU’s School of Communication as an artist-in-residence in the fall of 2002.

“Fall semester, I usually teach Film & Video 1, which is introduction to camera work, sound, some editing,” he said. “Then I have an all-graduate course in the weekend program called Developing Fiction Films, all about raising money through equity investors … In the spring, a sound design course and another course called Executive Suite, which allows our alums to Skype back onto campus.”

Now, those same students can hop on the Metro and head to the National Mall to see Professor Williams’ donation to the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture.

“My statuettes might inspire young people to understand that not only can they win Oscars behind the camera,” Williams said, “but you can fulfill your dream if you’re persistent enough.”

Listen to the full conversation with AU professor and two-time Oscar winner Russell Williams below: