Teachers throughout Maryland are back in the classrooms this week, working on bulletin boards and arranging desks as they get ready to welcome students back next week.

But at some schools, the teachers will face challenges and have to prepare for things you don’t expect a teacher to have to deal with.

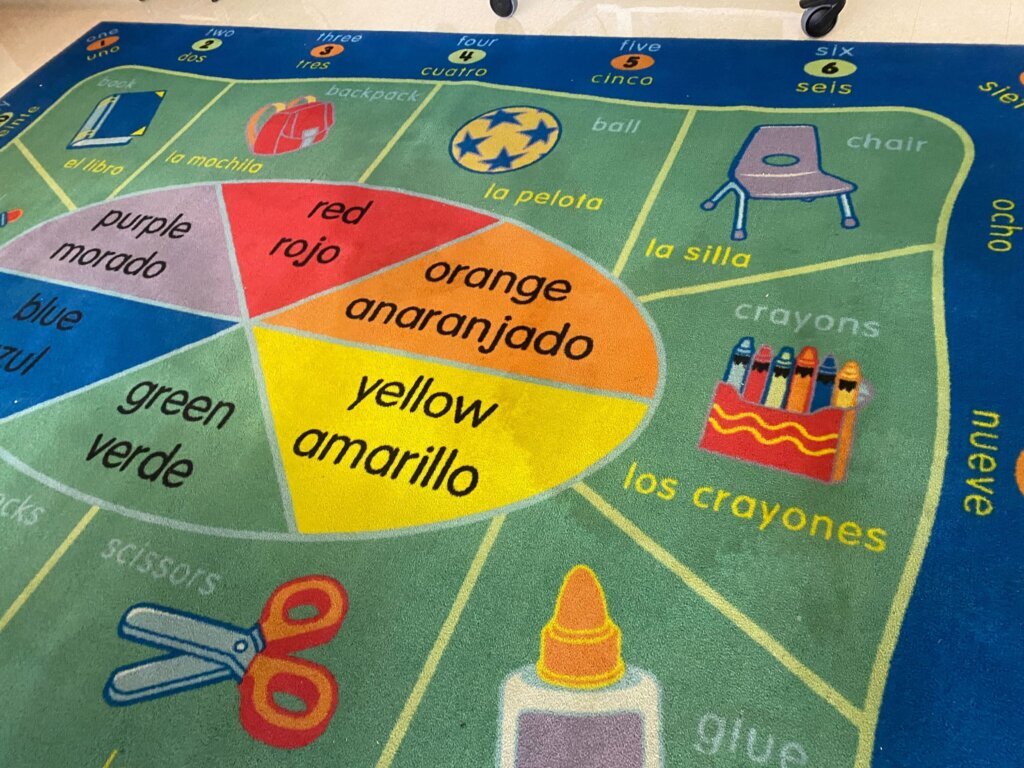

“We have students from over 30 different countries that speak over 20 different languages,” said Amy Robinson, the interim principal at Templeton Elementary in Prince George’s County.

They come from all over the world, too: Mexico, Guatemala and El Salvador, for example, as well as Nepal, Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria. One of the apartment complexes that houses newly-settled refugees is in Templeton’s boundaries, and several school buses are needed to bring students from there daily.

Teaching English-language learners is work that Robinson calls an honor. But she and other leaders here make clear to prospective teachers that “it’s going to be a different experience” than to what they may be accustomed to.

She didn’t have data on hand, but the reality is that if there are schools more diverse than Templeton in the area, there sure aren’t many of them. Robinson estimates about three-fourths of the student body learned another language before English.

“Our students are very eager to learn,” said Robinson. But in many cases, they might be starting over, if they’ve ever even been to school. And so besides being ready academically, “it’s important to make sure they know they’re welcome, to make sure they know that they’re safe, and to make sure that they know that we care about them.”

There’s a special program for students in their first year of American schooling to help ease those concerns and assimilate them into classrooms.

“It can be very scary to come from a place and have to learn everything brand-new,” said Stephanie Abraham-Middleton, who teaches students who have arrived in the United States within the last year.

Their first language isn’t English, if they speak any at all. Often, the way schools were structured in their home country are different.

For a child who grew up and later fled places surrounded by war and destruction, sirens during routine fire drills the U.S. might conjure traumatic memories.

“Making sure they understand what’s going to happen” is key, said Robinson. Initially, they’ll warn students ahead of time. “‘It’s going to be a loud sound. Here’s what we’re going to do. It’s just a drill. This is just practice. Everybody is safe.’ Making sure we do a lot of front-loading to help them understand that everything is OK; this is just practice.”

She added, “that siren or that loud noise, in their own experiences, may have a different meaning.

Even less extreme than that — but perhaps just as difficult — could be simply going to a different classroom as their sibling.

“Even as the year goes on, we have issues where a student will leave to go to the bathroom and make his way and check on his younger sibling in kindergarten,” said Robinson. “They have a very close bond to their siblings, and the older ones are very protective of their younger ones because, I think, of what they’ve been through together. They want to make sure that they’re safe.

Being separated from their siblings during school “can be a real trigger as well,” said Robinson. “It’s endearing to see how protective they are, but when you think about the reason why, it can definitely be a little heartbreaking.”

And then there are students who simply can’t communicate at all.

Irma Vasquez, a parent-engagement assistant at Templeton, recounted helping one new student, who didn’t speak English and didn’t have any way of identifying herself, catch the right bus home.

Vasquez saw another student who spoke some English talking to the new student.

“I said to this student from Afghanistan … ‘Is she your sister or sibling?’ ‘No, my neighbor,'” Vasquez recounted. “I called her mother … and said: ‘Can you call the parent? I need to find the name … and we need to send them back home safe on the bus.'”

But it’s not just the students who are “front-loaded” with information and preparation. Beyond just the concepts used to instruct students, the teachers are taught “trauma-informed instruction” and made aware of ways to help reduce cultural differences.

In the spring, that might mean setting up a separate space away from the lunchroom for students marking the Muslim holy days when they must fast, or getting the school cafeteria to offer more Halal options.

It’s work that goes beyond just teaching ABCs and math, but it’s work in which they take an immense amount of pride.

“We would not be here if it were not for these students,” said Abraham-Middleton.

“Everything we do, everything that we say, all of our actions revolve around: ‘How do we keep our students safe? How do we empower them? How do we give them the skills they need in order to go out in the world and to society and be the people that they are meant to be?'”

For new teachers, the five days they get this week to prepare is just a start.

“You do as much as you can to prepare, and we provide training at the beginning of the year, but throughout the year [too],” said Robinson. “We’re a community school, and learning is at the forefront of what we do, but we know that there’s so much more that goes into it.”