Years before Robert Oppenheimer led the Los Alamos lab that developed the first nuclear weapons, physicists in D.C. thrust the world into the atomic age — inside a narrow, zigzagging tunnel running underneath Chevy Chase.

“Totally by coincidence,” said Shaun Hardy, a librarian at the Carnegie Institute of Science.

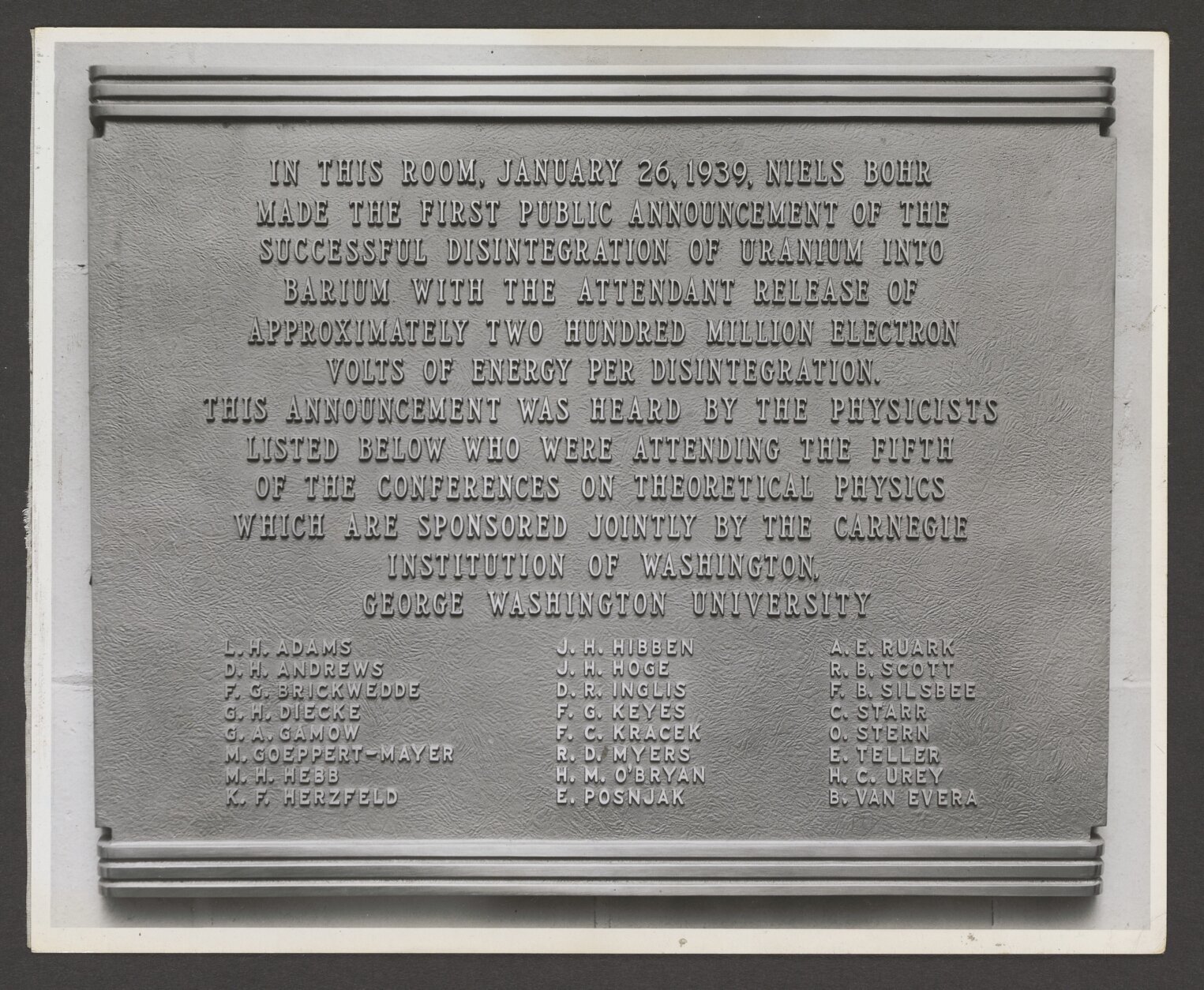

In January of 1939, Danish-physicist Niels Bohr was in D.C. for a physics conference at George Washington University. He had just learned that nuclear chemists in Germany had recently done the impossible — split a uranium atom — and decided to spill the beans to notable physicist Enrico Fermi.

“He and Fermi had the chance to talk privately at the meeting in person for the first time since those results were conducted,” Hardy said “And they agreed to announce the results to the gathered physicists there.”

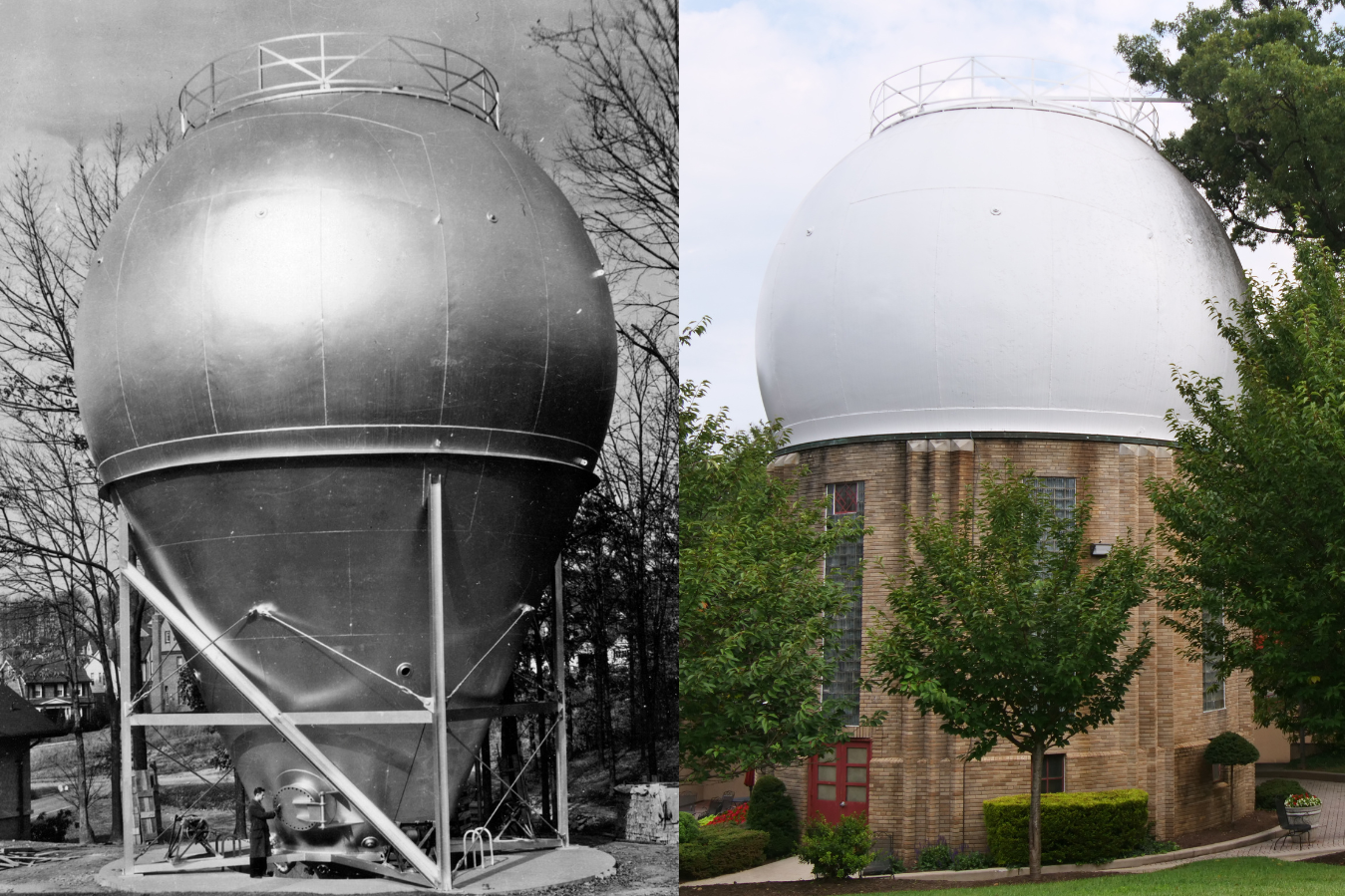

It just so happened the Carnegie Institute of Science in the Chevy Chase neighborhood of D.C. had just opened its Atomic Physics Observatory — a particle accelerator the neighbors called the “atom smasher.”

Stunned by Bohr’s announcement and armed with a new experimental technique, physicists raced north — likely up Connecticut Avenue — to Chevy Chase to prove to themselves and the world that nuclear fission was possible.

“They worked the whole day,” Hardy said.

Physicists set up the experiment inside a lab resembling a bomb shelter at the end of a zigzagging, concrete tunnel deep beneath a hill in Northwest D.C.

“By evening, they were ready to demonstrate it,” Hardy said. “And so the delegates from the conference, including Bohr and Fermi came here … where they stood and witnessed the splitting of the uranium atom with their eyes for the first time.”

Hardy said this was the dawn of the atomic age — and the world was about to find out.

A journalist from the now-defunct Washington Star, Thomas Henry, attended the physics conference at George Washington University. Henry was the first to print a story on the discovery.

“He was the first to break the news of experiment here, beating The New York Times by a day,” Hardy said.

Bohr’s announcement at the conference and the experiment at the D.C. “atom smasher” sparked similar experiments across the U.S., including at Oppenheimer’s University of California, Berkeley, campus.

“What happened was, in 1939, people started realizing, ‘Wow, you could take that (fission) and you could create a chain reaction with that process,'” President of the Carnegie Institute of Science Eric Isaacs said. “That then became the bomb.”

At the time, Vannevar Bush was president of the D.C. institute and also an early administrator of the Manhattan Project. In the new movie ‘Oppenheimer,’ Bush is played by Matthew Modine.

Despite the fact that D.C.’s “atom smasher” ushered in the atomic age, soon after this experiment, the Carnegie Institute of Science moved away from nuclear fission and instead focused on the proximity fuse — a technology that triggered an explosion when an artillery shell came close to its target.

Physicists helped develop and perfect this technology at the institute and at a used car dealership in Silver Spring, Maryland — which later became the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. It’s credited with saving hundreds, if not thousands, of lives by blowing up projectile weapons before they reached the ground.

As for the “atom smasher,” it stopped working in the 1970s and is now the last remaining particle accelerator of its time.

“The atom physics observatory is the only one left on the planet of its kind, of that era,” Hardy said.

It’s now used as a storage facility and as a stop along the tour of the Carnegie Institute of Science campus.