The paifang outside the Gallery Place-Chinatown Metro station, officially called Friendship Archway, is the most prominent symbol of the Asian American presence in D.C. But a lot of other, more hidden places had a historical significance to Chinese and Koreans in the District, and a research project is underway to mark them.

It’s called a historic context statement, and it hopes to provide a framework for evaluating sites for their importance to the story of Asian Americans in D.C. It’s the first-ever historic context statement on Asian Americans in the District, and also the first major study that’s been done on Asian Americans within historic preservation in D.C., said Sojin Kim, a senior consultant of the project, who also serves on the board of Asian and Pacific Islander Americans in Historic Preservation.

Kim called it “a wonderful affirmation of recognition that Asian Americans have been a part of D.C. and have been here for several generations.”

The study mainly focuses on Chinese American and Korean American communities, but Julie Park with the University of Maryland, one of the project’s advisers, said there are hopes to be able to branch out to other Asian Pacific American communities.

“It’s an important project to identify key locations and historical facts that we want to make sure that we make part of D.C. history,” Park said.

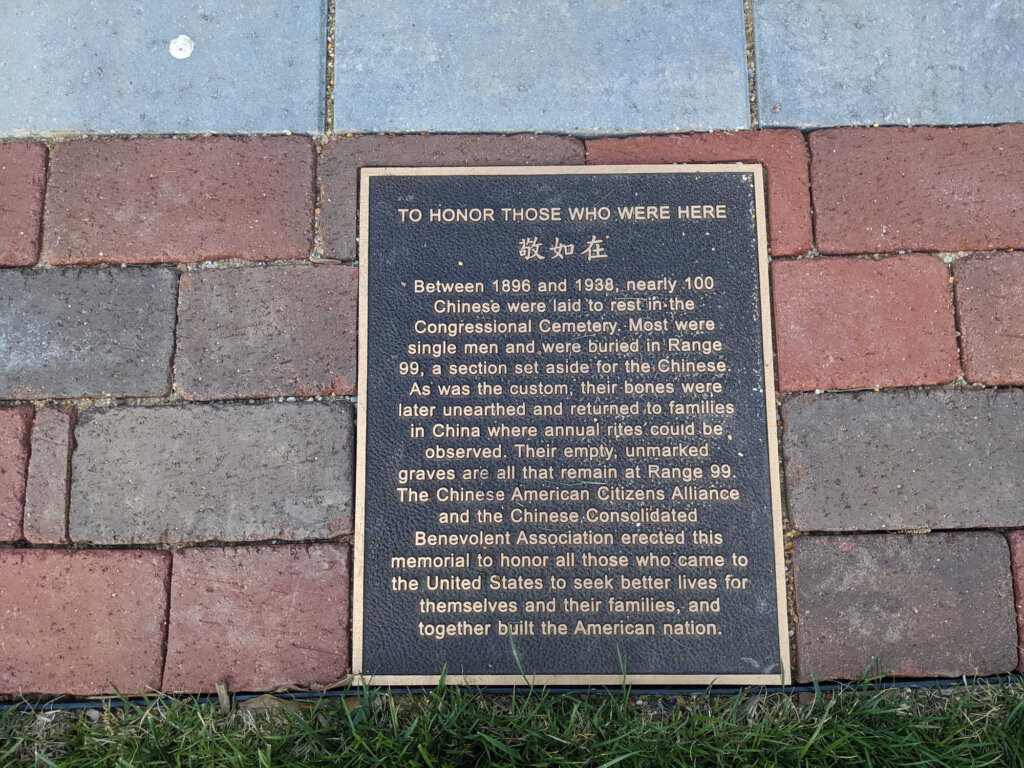

Several of the sites and places may no longer show any traces of how they were once a rich part of the Chinese and Korean experience in D.C.

But Kim said, “As the city changes, as the landscape changes … I think there still is value in recognizing these different histories that have been a part of the city.”

And with a study of any ethnic or racial community, she said it’s important to look beyond the obvious sites, or the sites that are exclusively one thing.

“Because people’s experiences are much more complex and varied than that,” Kim said.

(Click here to enlarge)

Adding a ‘complexity’ to DC history

Kim, who is also a curator at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, said D.C. has been defined by a Black-and-white binary in terms of thinking about race, ethnicity and diversity; however, Asian Americans “contribute a complexity” to how we think about community, race, and the intersection of race, immigration and migration.

The U.S. Census’ definition of who an Asian person is cites a wide geography of places a person may come or descend from to fall under the racial category. Park said that it’s important to note the differences among the group because it covers a broad area.

There are some overlaps in the history of Chinese and Koreans in D.C., and there are places where they actually came together, Kim said. But “the shapes of these communities and how they developed are just different.”

Chinese American history is better known, “just because there is actually a Chinatown in Washington, D.C. And whether or not people understand what Chinese American history is in D.C. based on that Chinatown, at least it’s on their radar,” Kim said.

Chinese immigration to the U.S. began during the California Gold Rush in the 1850s. In the D.C. area, communities and community institutions formed in the 1800s, comprising not just diplomats, but people who first came from China to California and then New York and finally to D.C., opening laundries, restaurants or import-export businesses.

“You have actually the formation of a concentrated Chinese American community from the late 1800s. And that’s really sustained till today, no matter how much smaller it’s gotten,” Kim said.

The history of Korean Americans in D.C. is not as well-known. A Korean Legation (essentially a smaller embassy) was established in the late 1800s, and its building in Logan Circle is still intact — the last such building representing 19th century foreign legations in D.C., Kim said.

Some of the Koreans who came worked for the legation; some sought a Western education; and some were exiles who had been involved in activities that were counter to the ruling government of Korea.

Besides Chinatown, Ben de Guzman, the director of the D.C. Mayor’s Office on Asian and Pacific Island Affairs, said there isn’t really an ethnic enclave in D.C. “But what that means for us is there’s so many different places, and different pockets of things that continually surprise you” — such as in Mount Pleasant, which is the Vietnamese community’s legacy home, or at the Philippine embassy, where the corner streets by Scott Circle are named after places in the Philippines.

“Different communities discover different parts of themselves and their histories that are kind of just secrets within their own communities. But we are always proud we get to be privy to those secrets,” de Guzman said.

- How to celebrate Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage month

- Balikbayan boxes: How Spam, toothpaste, even toilet paper can say ‘I’m thinking about you’

- How Chinese is Chinatown? The importance, and difficulty, of keeping historical connection

The ‘perpetual foreigner’

The historic context statement comes during a pivotal time, when reports of anti-Asian violence, including in D.C., were widely reported amid the coronavirus pandemic.

Scholars hope increased visibility of Asian American and Pacific Islander history in D.C. has an effect on the persistent image of Asian Americans as what Kim called a “perpetual foreigner.”

Michelle Magalong, a senior consultant in the D.C. study, agrees, saying that people assume that Asian Americans “just got here,” when they have been in the U.S. since the 1800s.

Kim hopes the study will convey that there have been Asian Americans invested and involved in D.C. for a long time, and will work against the persistent idea of Asians as foreigners.

De Guzman said even though the Asian demographic is not as large in the District as in other cities, they have not been spared from violence against the AAPI community — even de Guzman’s own staff has experienced it, he said.

But he sees examples of solidarity and healing, especially after the Atlanta shooting in 2021 that killed eight people, many of them women of Asian descent. He said two Black women from Ward 8 came to the office days after the shooting and asked, “How can we help?”

Researchers say the historic context statement will serve as a cogent narrative and start telling the story of “who was here, what they were doing, who were some of the important people, what were some of the important physical sites associated with these people and what they were doing,” Kim said.

And while Chinatown has very physical and visible landmarks in D.C., there are some communities, where you have to dig a little deeper; de Guzman said that his office is glad to have the stories of all Asian communities told.

“Whether they’ve been here for three years, three days or three generations, our community is very different from other AAPI communities around the country, and is very unique among our other communities here in the District,” he said.

Taking their places in history

Historic context statements have been done in Los Angeles and in Boston. They help support future nomination of historic landmarks.

“Particularly so that they could have the guidance in being nominated on to the National Register of Historic Places,” said Magalong, who is also a postdoctoral fellow in the historic preservation program at the University of Maryland and has done similar work for the City of Los Angeles.

The D.C. study is being done under the auspices of the 1882 Foundation, an education and civil rights organization based in D.C.’s Chinatown. The foundation has a program called Talk Story, where people gather to share stories about the community.

The research received funding — by way of the D.C. Office of Planning and the National Park Service — in early 2020, and the researchers had hoped to use the foundation’s programs and attract those who used to live in Chinatown, and who still come back to the area, to collect information from their stories.

But the coronavirus pandemic forced the researchers to rethink how to engage the community. They turned to Zoom, like most did, and despite some challenges, the team has been putting on a webinar with a new theme every month. They also created a website, AAPI in DC, as a way to share the work they are doing and engage the public. They have an active social media presence, as well.

“We wanted to put up a gallery, for example, of photographs that would help impress upon people that Asian Americans have been in D.C. for several generations,” Kim said.

Members of the team are also talking to people — as well as surveying historical materials about people, places and events in D.C. that relate to Chinese or Korean Americans — to complete their work. They hope to submit a full report by the end of the summer.