It’s easy to hear the word “emancipation” and immediately think of President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, which freed American slaves on Jan. 1, 1863. But in D.C., emancipation came earlier, and it’s still celebrated to this day.

The District’s annual Emancipation Day Parade and Concert Saturday started with a march from 10th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest to Freedom Plaza, at 14th Street and Pennsylvania. The concert featured performances by Faith Evans, Doug E. Fresh, Kenny Lattimore, MYA, Master Gee of the Sugar Hill Gang, EU featuring Sugar Bear and more.

D.C.’s Emancipation Day came April 16, 1862, eight months before the Emancipation Proclamation. It was the first time the government ever officially liberated any slaves. The much better-known proclamation only applied to the 11 states of the Confederacy (which didn’t include Maryland, Kentucky, Delaware and Missouri) and didn’t in effect immediately free anyone, since Confederate states of course didn’t feel themselves bound by it. Slaves were considered free when they either reached the Union states or the Union Army got to them.

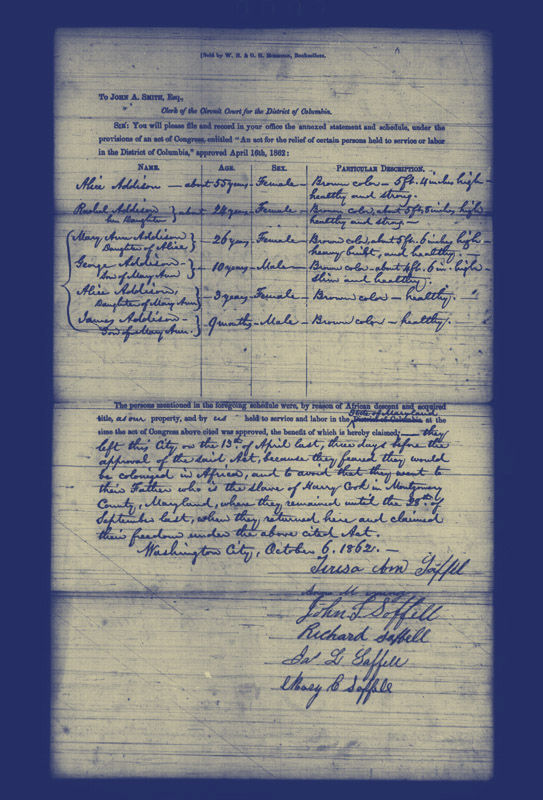

But D.C.’s Compensated Emancipation Act freed about 3,000 people with the stroke of a pen. It compensated the slaveholders for their “property” and gave freed black people money to emigrate if they wanted to.

![An Act of April 16, 1862 [For the Release of Certain persons Held to Service or Labor in the District of Columbia], also known as the Compensated Emancipation Act. (Courtesy U.S. National Archives Records Administration)](https://wtop.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/dcslavery-act-l.jpg)

![An Act of April 16, 1862 [For the Release of Certain persons Held to Service or Labor in the District of Columbia], also known as the Compensated Emancipation Act. (Courtesy U.S. National Archives Records Administration)](https://wtop.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/dcslavery-act-l-260x174.jpg)

“It puts the nation on a freedom road that is going take it not merely to the Emancipation Proclamation, but … through Juneteenth and the 13th Amendment,” said historian C.R. Gibbs, who has written extensively on D.C.’s early black history. “Emancipation in the District … is the first blow against the edifice of slavery by the federal government.”

A feature of the landscape

Since before the Civil War, the United States had already been calling itself “the land of the free and the home of the brave,” Gibbs pointed out, but its very capital was a center of the slave trade — auctions and slave pens were held near Lafayette Square, across the street from the White House, the White House Historical Association said. The slave trade in D.C. was eliminated by the Compromise of 1850, but in 1862, around 3,000 people were still enslaved in the District.

Slavery had been “a feature of the social scene and the economic landscape since before the founding of the city,” Gibbs said.

He recalled reading about a sign in the hallway of a D.C. hotel that boasted of roomy underground cells for congressmen’s slaves, “and that their enslaved people would be well cared-for. But if they should escape, the hotel would pay the value of the escaped party.”

It wasn’t just part of the fabric of the society, but of the whole city, including the Capitol. A 2005 report from the Architect of the Capitol said, “It is not possible to examine the documents … relating to the Capitol’s early construction without being impressed by the sheer number of references to ‘Negro Hire.’”

The report explains that the area that became Washington, D.C., is, to put it bluntly, a kind of weird place to put a national capital. It was set in “the sparsely populated agrarian context of the Maryland countryside” where there weren’t a lot of skilled craftsmen in the area; “the only human resource that the neighborhood could supply in abundance was unskilled labor — mostly slaves, but a smattering of free blacks and whites as well.”

Captain George Pointer hauled marble on the Potomac to help rebuild the Capitol after the War of 1812, eventually earning enough to buy his freedom. Philip Reid was an enslaved laborer in the foundry of sculptor Clark Mills, and helped make the statue of Andrew Jackson in Lafayette Park and, ironically, the Statue of Freedom that sits atop the Capitol to this day.

Resistance ‘large and small’

The process leading to emancipation wasn’t a smooth one. “I have never doubted the constitutional authority of Congress to abolish slavery in this district,” Lincoln said in his statement when he signed the act, but Lincoln himself, as a member of the U.S. House in 1849, introduced a D.C. emancipation bill that went nowhere.

Slavery’s demise “was valiantly fought for by people of conscience for decades,” black and white, Gibbs said, adding, “it is critical that we understand that black folk resisted in ways large and small.”

Those efforts inspired a backlash, sometimes a violent one. D.C. was a heavily black city, but throughout the 1800s, a series of events heightened the oppression of black people, even those who weren’t enslaved, in the District.

The Black Codes, which began in 1808, put limits on the freedom of all black people, including those who weren’t slaves. The curfew for black people was 10 p.m. Slaves obviously couldn’t pay the fine, so they had to ask their masters to do it; if they didn’t, the punishment was whipping.

A few years later, the codes were made more restrictive, and by 1821, free black people had to pay a $20 “peace bond” to a “respected” white man as a hedge against assumed future bad behavior. When one man challenged the bond, the judge only ruled for him in the narrow sense that the bond couldn’t be charged to those who were already residents when it was instituted.

In 1846, Congress voted for Alexandria, then a part of D.C., to return to Virginia, where among other restrictions black people weren’t allowed to go to school.

After the Nat Turner Rebellion in 1831, many white people considered abolitionism a form of terrorism, and claimed that violent oppression of abolitionists was merely self-defense. After that, some of the racial oppression in the District turned violent.

In 1835, the widow of William Thornton, the architect of the U.S. Capitol and the Octagon House, was allegedly attacked by a slave, and a mob tried to snatch the defendant from jail. Failing in that, they ransacked the black-owned Epicurean Eating House, at 6th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue in Northwest, and other black people’s homes churches, businesses and schools.

On the night of April 15, 1848, the schooner Pearl left The Wharf, in Southwest, with 77 escaping slaves. They made it as far as Point Lookout on the second day before everyone on board, including the captains, were arrested.

‘I would get on a Jolly spree today’

The Compensated Emancipation Act was written and introduced by Henry Wilson, who went on to be vice president under Ulysses S. Grant, in 1861.

Early in 1862, while the bill was begin debated, the abolitionist Sen. Charles Sumner, of Massachusetts, confronted Lincoln. Gibbs recalls reading that Sumner asked the president, “Do you know who, at this moment, is the largest slaveholder in the United States?”

Lincoln didn’t know. Sumner replied, “You are.” As the chief executive, and with the federal government controlling the District, Sumner argued Lincoln was responsible for the continuation of slavery in D.C.

After the Compensated Emancipation Act was passed, applause reportedly broke out in the Senate chamber. Lincoln signed the bill into law April 16, 1862.

“All persons held to service or labor within the District of Columbia by reason of African descent are hereby discharged and freed of and from all claims to such service or labor,” the act read; “and from and after the passage of this act neither slavery nor involuntary servitude except for crime where of the parties shall be duly convicted shall hereafter exist in said District.”

In the book “The Negro’s Civil War,” author James M. McPherson reprints a letter from a free black citizen of D.C. who wrote that he told two women about the emancipation: “When I had finished, the chambermaid had left the room sobbing for joy. The slave [woman] clapped her hands and shouted, left the house saying, ‘let me go and tell my husband that Jesus has done all things well.’”

The man added, “Were I a drinker, I would get on a Jolly spree today, but as a Christian I can but kneel in prayer and bless God for the privilege I’ve enjoyed this day.”

“There were people who just erupted in joy,” Gibbs said.

The inclusion of compensation for slave owners can be read as a concession to the concept of people as property, but Gibbs said at the time, it was probably for the best.

The compensation “was one of the few ways left open to people who sought to deal with the problem with other than conflict.”

The idea was already “in the air,” Gibbs said; England and Mexico had “held out the promise of compensated emancipation.” And in his Second Annual Message to Congress, Lincoln had proposed compensated emancipation for any state that freed their slaves by Jan. 1, 1900.

The important thing, Gibbs argued, was to get some kind of emancipation rolling. “That action — the success of emancipation in the District — opens him up in June … to sign legislation to end enslavement in the western territories. And then in September, we get the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation,” Gibbs said.

Of course, it wasn’t all that simple: Slavery was still legal in Maryland, and the Fugitive Slave Act was still in effect, which made the District a destination for slaves seeking freedom — and gangs looking to bring them back. “[Just] because there was emancipation in the District did not mean that your life [was] in danger if you had gone across the Navy Yard Bridge and gotten away from your master.”

Still, it was a step, and an important one. As the 2005 Architect of the Capitol report said, it’s not known whether Philip Reid was in the crowd the day the Statue of Freedom was set atop the U.S. Capitol in 1863. But when he helped make, it he was a slave, and when it was unveiled, he was free.

Celebrations then and now

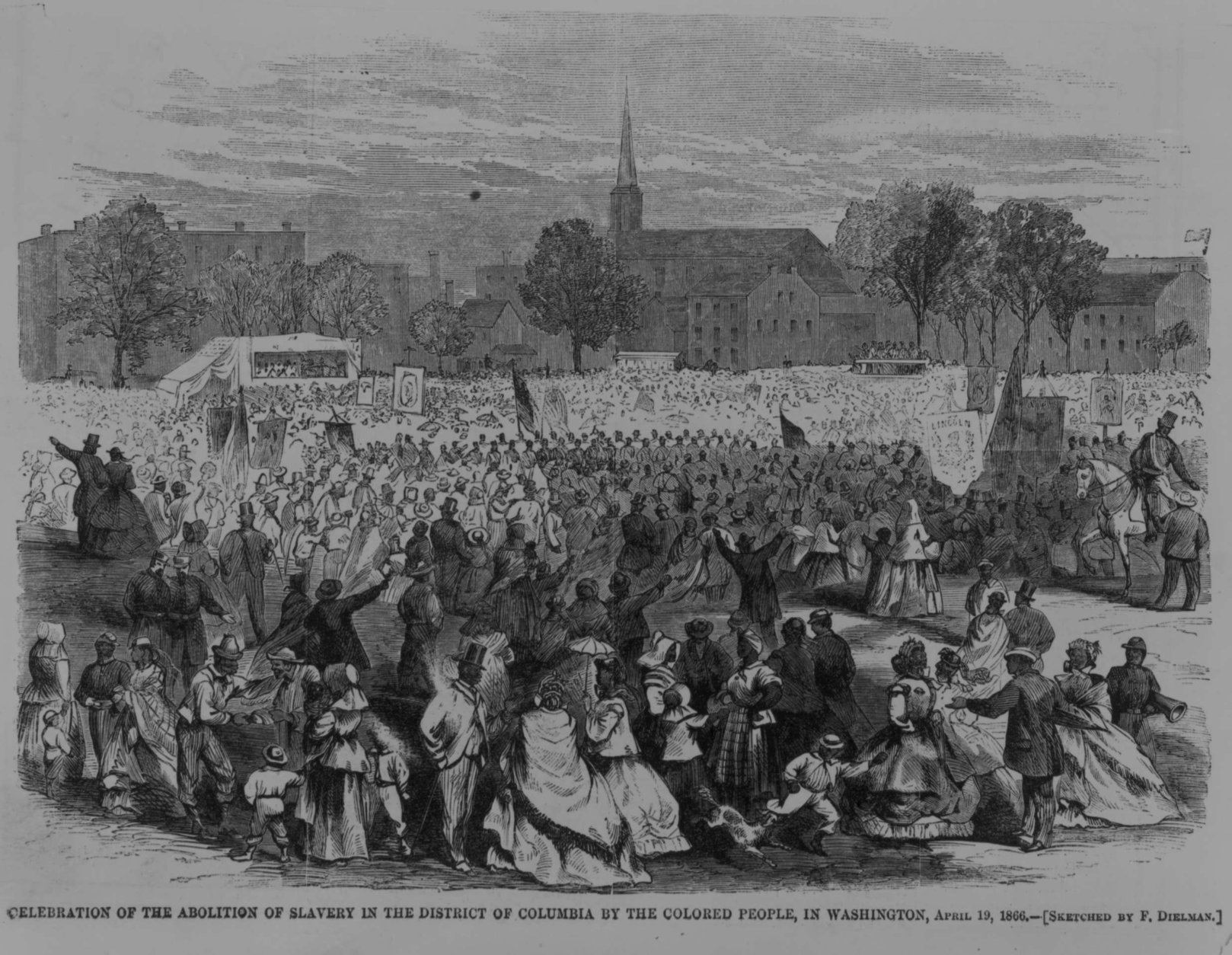

The first D.C. Emancipation Day parade was delayed by the “body blow” of Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, Gibbs said, but celebrations happened in the black church community, as well as on the Fourth of July that year. On April 19, 1866 (after a three-day rain delay), D.C.’s first Emancipation Day parade stepped off from Franklin Square, at 13th and I streets in Northwest.

It was led by “Alfred Kiger, a hackdriver who lived on H Street NW and was the parade’s chief marshal,” Gibbs wrote in The Washington Post in 1985. “He wore a yellow sash with pink trimmings atop his broadcloth coat.” He was backed up by assistants wearing blue sashes, two units of black troops, representatives of D.C.’s black societies and more.

The parade lasted until 1901, when years of infighting between organizers took its toll. Gibbs said the celebration continued in the black church community, but official celebrations weren’t held.

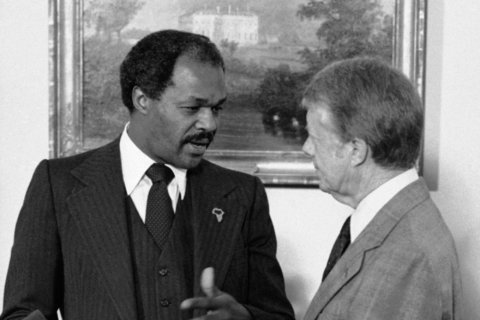

Then-Mayor Anthony Williams set up a commission in 2004 that recommended making Emancipation Day a District holiday — the only local holiday on the calendar — but before that, “I don’t think it was celebrated” officially, said D.C. Council member and former Mayor Vincent Gray.

He remembers the first modern celebration, in 2005, as “a very celebratory moment,” but added that it’s an important reminder not only of what’s been accomplished, but what hasn’t been: “[It’s] obviously something to celebrate, that at least some people in the District of Columbia were freed.”

Gray said the Emancipation Day celebration is partly about having a good time: “It is fun, absolutely. It’s wonderful to watch the number of people who come out; it’s wonderful to watch people interacting in ways they otherwise might not.”

But, it’s also connected with the campaign for either statehood or full recognition in the U.S. Congress — what Gray calls “part of being able to be a free entity — to be able to enjoy the same rights as anybody else, which we do not at this point.”

He pointed out that D.C. has a larger population than Vermont or Wyoming, and pays more than most states in per capita income tax. “We pay our way; it’s time now for America to pay us back with the freedom we deserve,” Gray said.

“Even though we don’t have the same yoke of racism around our necks as we did then, we still aren’t free. And we’ve still got lots of work to do to help people understand that the freedom that other people enjoy has not arrived in the District of Columbia yet. And there’s still more to do.”