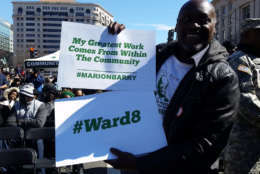

This is the second part of WTOP’s three-part series “The making of Marion Barry,” marking the 40th anniversary of the first election of the man referred to as D.C.’s “Mayor for Life.”

WASHINGTON — In 1950, the U.S. Census found that 64.6 percent of the population of D.C. was white and 35 percent black; in 1960, it was 45.2 percent white, 53.9 percent black.

By the time future Mayor Marion Barry arrived in Washington in 1965, the city was 66 percent black. But, the president of the Board of Commissioners, a three-member executive board appointed by the U.S. president — and the closest thing D.C. had to a mayor — was white. Virtually all of D.C.’s police officers and firefighters were white.

The House and Senate committees that made the laws for the District were overwhelmingly white and Southern — John McMillan, a Democrat from South Carolina who headed the House District Committee for 24 years, once mailed Mayor Walter Washington a watermelon, calling it “a letter from home.”

“In 1964,” Barry wrote, “if you were heading down South from New York and sitting in the front section of the train, you would get up and move to the back section once you reached Washington. But, if you were coming from the South and headed North, you would start out in the back section of the train and move to the front once you got to Washington.”

Read Part 1: “DC mayor’s activist beginnings in the South

Read Part 3: ‘There was no way we could win’

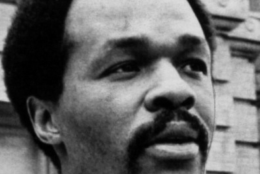

By January 1966, Barry was organizing a bus boycott — he called it a “mancott’’ — in D.C., protesting a 5-cent fare hike. The increase was rescinded the next day. It was the first victory for Barry’s “Free DC” movement, an attempt at organizing the black population and creating genuine home rule.

Speaking to the Marion Barry 1978 Mayoral Campaign Oral History Project at the George Washington University’s Gelman Library, Max Berry, who became the finance chair of Barry’s 1978 campaign, remembered his first impression: Barry would stand in the park in a dashiki “speaking to anybody who would speak to him. It was almost like London in Hyde Park, only he wasn’t crazy or anything; he was just talking about the District. … I was immediately sort of impressed because I thought I was going to get … the wild guy to try to sell me something ridiculous, and I could tell he was a man of intelligence, even though he looked a little funny to start with.”

And Barry made waves. After the 1968 uprising in D.C. in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Barry said, “White people should be allowed to come back only if the majority of the ownership is in the hands of blacks. That is, they should come back and give their experience and their expertise — and, then, they should leave.”

After the 1969 moon landing, he wondered out loud, “Why should black rejoice when two white Americans land on the moon when white America’s money and technology have not even reached” the inner city.

But, even by then, Barry had left the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which was beginning to associate with a more radical activism. In 1967, he launched the first version of a program whose legacy would follow him the rest of his life: the jobs program Pride Inc.

Pride Inc.

“How does one begin to measure dignity and hope?” Barry says in an old piece of film used in the documentary “The Nine Lives of Marion Barry.”

Pride Inc., which Barry organized with his then-wife Mary Treadwell, as well as local activists Carroll Harvey and “Catfish” Mayfield, gave jobs to young people and to adults, the latter group often including ex-offenders. It also showed the range of Barry’s political and communications skills. It was funded by the U.S. Department of Labor, as Barry worked with Labor Secretary Willard Wirtz.

One of those kids was Gerald Bruce Lee, an Anacostia kid who, in 1967, got a Pride Inc. job sweeping streets.

“It changed everything,” he told WTOP. “I learned leadership; I learned how to work … It opened up a lot of doors and windows of opportunity. …”

“And, the beauty of it was we were cleaning up our own communities. We were working and earning funds that we could take home. … You go into a community where there’s trash and dirt, and you clean it up. And, it looked good. And, you felt pride in it,” Lee said.

By 1969, Pride Inc. was connected with American University, and students could get help with applications and interviews at various colleges. Lee and several of his friends were admitted to American before they’d finished high school.

“For most of us in that group, we had never thought about college,” he said.

The truth is, it not just changed my generation, but my son’s and my grandson’s generation.

— Gerald Bruce Lee, retired federal judge

Lee went to his first college class – “baseball caps cocked to the sides, sunglasses” – and remembered thinking, “My mother told me that people who went to college had to be really smart. And, I sat there and listened, and … I heard the teacher say something, and I thought, ‘I was thinking that.’”

His eyes opened to even more possibilities. “They picked us up at the corner of 16th and U Street … and drove us up Massachusetts Avenue. As I was riding up Massachusetts Avenue, I saw manicured lawns and fountains. [I asked] ‘Is this somebody’s house? Is this Washington?’ They said, ‘Yes, this is Washington, D.C.’”

Lee retired last year as a district judge for the Eastern District of Virginia. “I don’t think American University would have looked at me, coming from Southeast, were it not for Pride,” he said.

Pride also worked with ex-offenders, including those who were driven by drug problems. They got counseling and training, and some of them went back to crime. But, more succeeded, Lee said.

“Who wanted to take the ex-offenders? Well, Pride did. We embraced them. We knew they were part of our family and our community,” he said.

Lee had a supervisor who earned his high school diploma at the prison in Lorton, went to college with the help of Pride, and helped others do the same. Other Pride workers, including ex-offenders, were trained in professions such as computer science and accounting.

“The truth is, it not just changed my generation, but my son’s and my grandson’s generation,” Lee said. Barry and Treadwell “were determined to show that there was talent in our community that just needed an opportunity.”

From defendant to the D.C. Council

Even then, Barry was being arrested by the D.C. police on charges such as jaywalking and ripping up a parking ticket. But, it wasn’t long before Barry began looking at ways to accrue more power and make more changes in the District.

In 1972, as part of the gradual implementation of home rule, the D.C. School Board was the highest office that D.C. voters could choose directly. Barry ran for the presidency of the board and won. In 1974 and 1976, he won and kept an at-large seat on the D.C. Council.

“It was exciting to us,” Lee said. “The idea that the Marion we knew … wanted to go inside was huge. … It was an exciting time to see that someone we knew, who cared about the community, who cared about us, was going to become a member of the school board.”

In 1964, if you were heading down South from New York and sitting in the front section of the train, you would get up and move to the back section once you reached Washington. But, if you were coming from the South and headed North, you would start out in the back section of the train and move to the front once you got to Washington.

— Marion Barry

On the council, Barry was chairman of the Committee on Finance and Revenue, where he combined his activism with his head for numbers.

“You had to be able to count,” former Washington Post writer Milton Coleman told the GW project. “And, folks always felt black folks can’t count.”

In a report issued during the summer of 1975, Barry wrote, “Every time the District is faced with a financial bind, the same tired ‘solutions’ are trotted out: more income taxes, bigger sales taxes, increased property taxes. Perhaps our city administrators figure that the taxpayer is so dispirited that s/he can tolerate anything.”

He also called for a commuter tax, arguing that “nearly every major city in the nation has a nonresident income tax and every single state, which has an income tax, has the authority to tax nonresident income earned outside its boundaries. Yet, in the District, we are forced by Congress into a situation where we must subsidize suburbia by imposing ever higher tax rates on District residents and businesses.” (There is still no commuter tax in the District.)

At the same time, Barry continued to operate as an activist. Richard Maulsby, the founder of the Gertrude Stein Democratic Club, D.C.’s oldest gay Democratic association, told the GW project, “I can remember [Council President] Sterling Tucker slinking into a Gay Pride Day event when it was down at the Lambda Rising [book store] on R Street, like 6 o’clock, after everybody had left. But, Marion was there in the middle of the whole thing, giving a speech, rousing people up, working the audience. I mean, there just wasn’t anybody like him on the City Council.”

It wasn’t long before people were thinking of him as a potential mayor. A stroke of fate in 1977 raised his profile even higher.

The shooting

On March 9, 1977, a dozen gunmen from the Hanafi Muslim sect stormed the headquarters of B’nai B’rith International, near 17th Street and Rhode Island Avenue in Northwest; the Islamic Center of Washington, on Massachusetts Avenue; and, finally, the District Building (now known as the Wilson Building) in downtown. They took 149 hostages for 38 hours, and in the takeover of the District Building, killed security guard Mack Cantrell and 24-year-old WHUR reporter Maurice Williams.

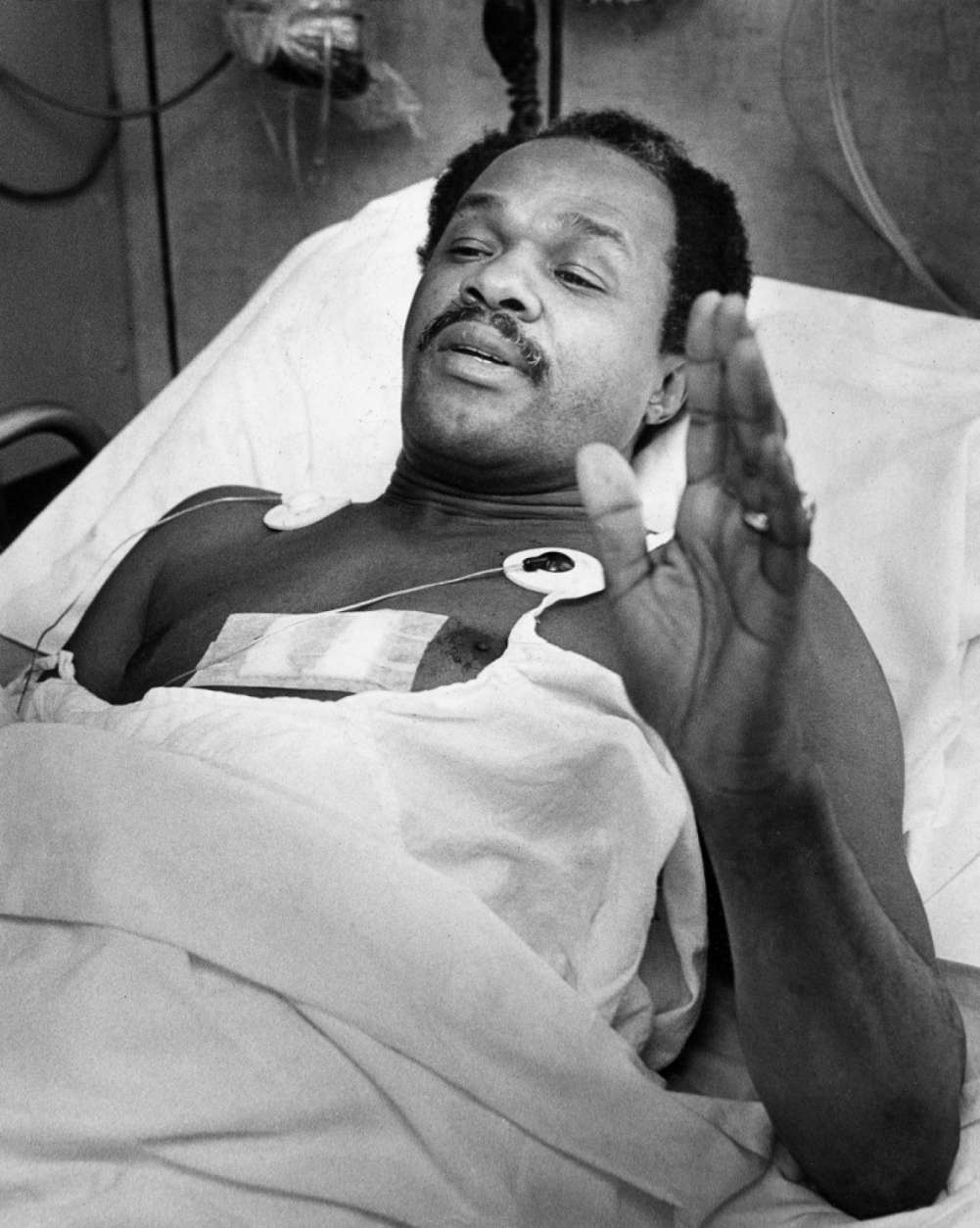

Barry was wounded in the gunfire — it wasn’t a serious injury, but a shotgun pellet had lodged an inch or so from his heart. His former executive assistant, Patricia Seldon, told the GW project that firefighters put a ladder to a fifth-floor window, strapped Barry to a stretcher and hoisted him down to a waiting ambulance.

“I can still see that picture in my mind, because he was strapped onto this ladder … and he was waving to people. … I think the next day, the picture in the paper was him waving, and strapped some kind of way.”

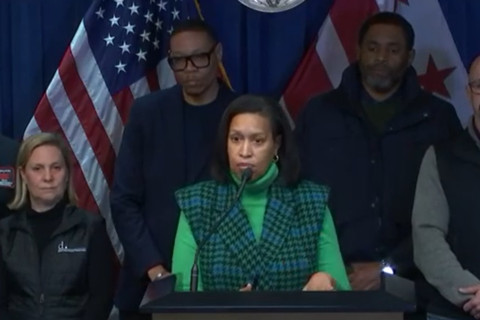

Then, in January 1978, Barry announced his candidacy. But, with the sitting Mayor Walter Washington and Council Chairman Sterling Tucker standing between him and the Democratic nomination, it looked like a long shot.

Barry wrote, “I learned early on during my civil rights activism that dangerous events can either slow you down or speed you up.”

He claimed that supporters started to put together a campaign organization “without me really knowing or asking,” and that may be true, but Sterling Tucker, the D.C. Council chairman whom Barry beat in the primary, recalled, “Oh, Marion came to the council [and] we knew Marion was starting to run for mayor.”

Delano Lewis, who worked for the C&P Telephone Company, went on to become president and CEO of National Public Radio and later served as U.S. Ambassador to the Republic of South Africa, told the GW oral history project: “I got a call from Marion, and he said, ‘Del, I’m going to run for mayor, and I want you to help.’ And I said, ‘Why do you want to do that? You just got shot in the District Building.’ He said, ‘That’s the reason.’”

“He said, ‘I might not be around. That’s why I want to run.’”

In Part 3: “There was no way we could win, except we did” — the people who worked to make Marion Barry mayor look back.