WASHINGTON — In D.C., you can stumble over history and not even know it.

Never has that been more true than when it comes to America’s first federal monuments — D.C.’s Boundary Stones.

The 40 stone markers were set in place by President George Washington to designate the border of the nation’s capital. The 10-by-10-mile square includes a stone marker every mile.

The physical boundary was the beginning of Federal City. The District. The first mewling scream of Washington, D.C., as the newborn capital of what would become the most powerful country on the planet.

Amazingly, nearly all 40 of those stones still exist today, but few know about them. And fewer still have taken up the mantle of preserving them.

Those few are the heroes of this story, toiling in relative obscurity to preserve the greatest artifacts America has — the story of us.

Some stones, such as the one at Jones Point, Virginia, have an Indiana Jones air of mystery about them.

It is partially underground, near the shore of the Potomac River, protected by a brass-lined window. Others have had worse fates — being demolished by a bulldozer (NE1) or smashed by cars (SW6).

The NE3 stone resides at the edge of a McDonald’s parking lot, surrounded by broken beer bottles and trash.

Like everything in America, there’s a story to the stones. And, like everything in D.C., it’s a precarious, convoluted mess of politics, money and geography.

To make matters worse, in true bureaucratic fashion, not a single government entity involved with the stones seems to know exactly what’s going on.

Making a city

View the location of each boundary stone in our interactive map above. For a full-screen version, click here.

After the Revolutionary War, the new United States fought over where to put the nation’s capital.

From 1785 to 1789, it operated out of New York City’s Federal Hall. But the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1789, changed all that, giving President Washington the power to create the capital along the Potomac River.

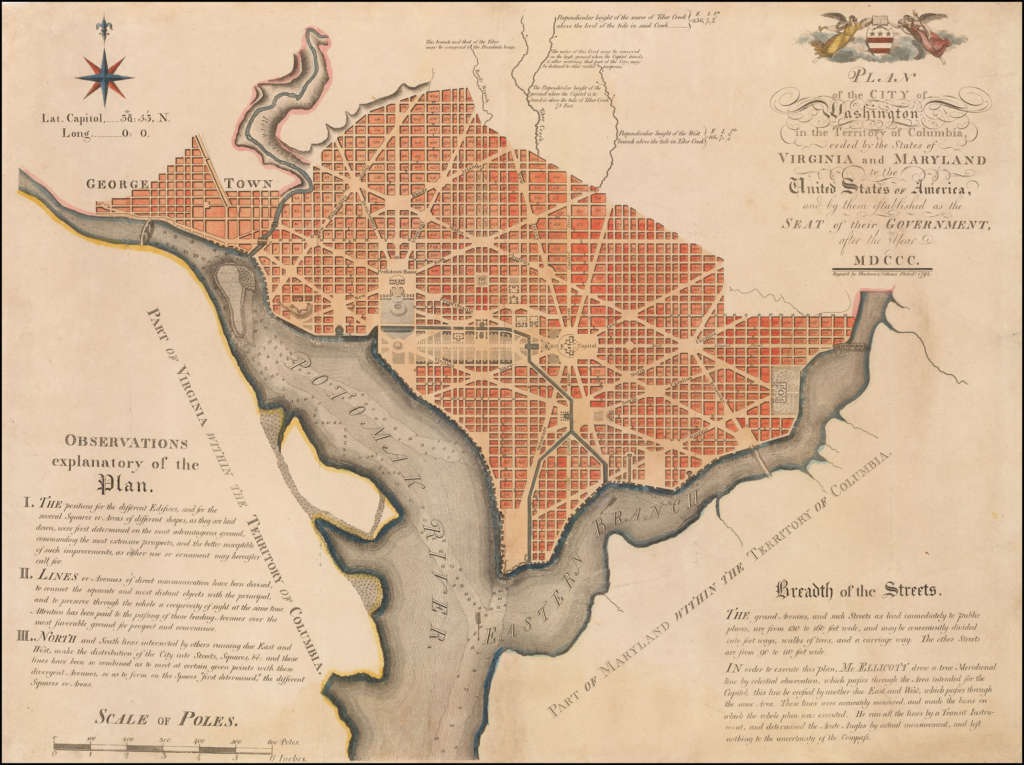

The city was to be a “10 Miles Square” of land that Virginia and Maryland were going to donate — 100 square miles altogether.

George Washington chose the geographic location he did for many reasons. Chief among them was the fork in the Potomac and Anacostia rivers, two established local ports with Alexandria and Georgetown — besides, he already owned the land.

But Congress didn’t entirely trust Washington.

“Congress was very leery of George Washington because he owned a lot of land in Virginia — a tremendous amount of land,” said Stephen Powers, co-chair of the Nation’s Capital Boundary Stones Committee. He has a book coming out in December about the stones.

So Congress blocked Washington from profiting directly from the placement of the Federal City.

In order to establish the new city, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson hired a surveyor by the name of Andrew Ellicott — whose father, Joseph Ellicott, founded Ellicott City, Maryland.

“Ellicott had all the survey instruments and was a kind of renowned colonial surveyor who, by the time his career was over, laid out state boundaries [of] 11 different states,” Powers said.

Andrew and his brother Joseph Ellicott started the survey in February, 1791. They hired astronomer Benjamin Banneker, a free African-American, to make observations and calculations. It took them 34 days to make the loop around the District, chopping down trees as they went. For the next year and a half, loggers chopped down trees for 20 feet on both sides of the boundary line — for 100 miles.

The first stone was laid April 15, 1791, in what are now the grounds for the Jones Point lighthouse in Alexandria, Virginia. At the time, it was a ceremonial gesture — the stone was replaced by a more proper monument in 1794.

Legend has it that “Banneker fixed the position of the first stone by lying on his back to find the exact starting point for the survey … and plotting six stars as they crossed his spot at a particular time of night,” according to Powers’ site boundarystones.org.

The stone had an inscription on it: “The beginning of the Territory of Columbia.”

Ellicott and crew then headed northwest toward Falls Church, Virginia, laying stones as they went. The next destination was Silver Spring — known as Woodmont at the time — then Seat Pleasant, then back down to the Potomac.

On Jan. 1, 1793, roughly 23 months after the project started, Ellicott gave Jefferson the final report and an intricate map. And with that, the Federal City was set in stone.

Where are they now?

The trek to visit the locations of the 40 Boundary Stones — 36 of the originals from the 1790s remain, the other four are replicas — can warm the heart, and sometimes pierce it.

People along the boundary are happy to discuss the stones. Homeowners with stones on their property are generally willing to let the curious take a closer look — provided they’re respectful.

There’s a reverence for the monuments held by communities who know what they are.

Visiting the West corner Boundary Stone in Falls Church, Virginia, is a fairy-tale experience. There’s a slow drive up North Arizona Street — the homes there a mark of affluence, the road lined by lush plants and color.

On the left, just a little ways before North West Street, is Andrew Ellicott Park. A pocket park. You can leave your car on the side of the road, step out and walk into a gorgeous clearing domed by the tall arching branches of trees above.

In the center is the original West Boundary Stone, ringed by a five-foot fence installed and well-maintained by the Daughters of the American Revolution. Three plaques along the enclosure proudly note the importance of the small rock — when it was installed (1791-1792), dedicated (1952), then rededicated (1989).

In stark contrast is NE3, which sits at New Hampshire Avenue Northeast, Eastern Avenue and Chillum Road at the edge of that McDonald’s parking lot, down a small hill. A small sign there drilled in by screws, not a plaque, said that NE3 is protected by the flag chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

But the fencing is in poor shape. Part of it is missing — seemingly cut away. Other parts are bent. The paint on the metal of the fence has worn away and rust shows through. Weeds clutter the site. Trash surrounds the stone, including junk food wrappers, booze bottles and the cardboard from a 2-pack (we swear) of Heineken.

“It’s unfortunate, because the Boundary Stones are our oldest national monuments, and so many people don’t know about them,” Penny Anderson, a teacher from Spotsylvania who helps care for the stones, told WTOP as she drove south away from NE3.

“I think part of it is neglect. It is out of sight, out of mind.”

Even when they are in sight, they are out of mind.

Anderson told WTOP about going to visit the SE1 stone in Seat Pleasant, Maryland, which is near a corner wall of the National Capitol Hebrew Cemetery. She was there to take photos.

A passerby pointed to the Boundary Stone and asked Anderson who was buried there, outside the cemetery.

There’s also a complicated question: Who owns the stones?

“In the 1800s, when Virginia retroceded the land back from the Federal City, the Boundary Stones on the Virginia side” became the property of the landowner, Anderson said.

“So it was no longer a monument that was done by the federal government. … I’m sure there’s a line item somewhere in somebody’s budget because the fencing around from the Daughters of the American Revolution are still being upkept.”

Don’t take them for granite

So how much money goes toward preserving the oldest federal monuments in U.S. history? Who pays? And for what?

This is where it gets a little rocky, because nobody seems to know — even when they’re doing the work and winning awards for it.

“A lot of these stones sit in people’s yards, and there’s a lot of coordination [needed] to actually work on them,” said Moss Rudley, acting superintendent of the Historic Preservation Training Center.

The Center entered into an agreement with the District Department of Transportation to do a preservation and conservation project for the stones currently within D.C.’s boundaries.

Those particular stones are “assets of the Department of Transportation … They are the owners of those stones,” Rudley told WTOP.

Their work with the stones was a one-time project that took around three years. Rudley puts the budget for the project at around $100,000. The group did such an exceptional job it earned DDOT the 2017 Award for Excellence in Historical Preservation.

But he notes that he doesn’t know where the money comes from.

“I don’t know how the District of Columbia received their funding for the project. … We’re a fee-for-service operation and we do partner with other federal agencies and local governments to bring training and help support their preservation needs,” Rudley said.

The Historic Preservation Training Center was contacted by the District of Columbia’s Historic Preservation Office originally to see whether they were interested in doing the work because they felt it was very hard to define, Rudley explained.

He said it was also logistically challenging.

“Those are all kind of things that we specialize in doing … Then we also coordinated with the Daughters of the American Revolution chapter in D.C. that, actually, they own and take care of the cages that are around [the stones],” Rudley said. “There’s a very kind of … web of ownership.”

So, the Boundary Stones are federal monuments that aren’t treated like any other federal monuments? Correct, according to Rudley.

As such, the duty of preservation falls to small groups of dedicated people, including Powers, Anderson (whose email spurred this investigation), Rudley and his team, and the Daughters of the American Revolution, who have a long history of taking care of the Boundary Stones.

“The National Park [Service], they got a $100,000 grant, and I’m not sure where that grant came from exactly,” Janet McFarland, state regent for the Daughters of the American Revolution, told WTOP.

“With that grant, they were going to go around, there were a couple stones that had deteriorated completely,” and they were going to perform upkeep on the stones, McFarland said.

But there has been so much confusion about who is supposed to do what and when and where the money might come from, that it creates a difficult task.

“One thing that gets really funky with these things is, the Park Service owns the little piece that’s the fence enclosure and the stone, but then [SE5], it’s on the Metro grounds, so if you want to erect a sign, now we’ve got to get DDOT involved; we’ve got to get Metro involved, you know,” McFarland said.

“So now, in order to accomplish something, you have a million different people that you have to coordinate with.”

For the District, the stones are ostensibly owned by DDOT, but the literal ground they sit on is owned by the National Park Service. Unless they are part of retroceded Virginia, wherein homeowners own the land. But the stones are federal and the cages surrounding them are maintained by volunteers.

It’s like a Russian nesting doll of ownership. And there are no easy solutions.

McFarland said that at one point, DDOT became a serious impediment to maintaining the stones. They wanted the Daughters of the American Revolution to pay for permits to do upkeep.

“And in my head, I’m thinking — because these were the ‘new rules’ that were laid down — this is crazy,” McFarland told WTOP.

One of Anderson’s ideas was that area schools or businesses could adopt nearby stones and help take care of them.

“I think if we get that connection and that ownership, even for one stone, that’s going to increase the connection with the public,” Anderson said.

McFarland agreed, and noted that some kind of educational module or plaque could help D.C. students and the public understand the stones’ importance.

“Because it’s really part of their history,” she said, and went on to point out how it could increase community pride.

According to Anderson, getting all of the stones registered as national landmarks would at least be a step in the right direction.

“In 2012, the Office of Planning’s Historic Preservation Office undertook the first comprehensive survey and conditions assessment of the Boundary Stones to develop the plan for their conservation and protection that was later carried out by the National Park Service and others,” D.C.’s Office of Planning said in a statement to WTOP.

“In 2017, our office presented a preservation excellence award to the NPS, District Department of Transportation, U.S. Department of Transportation, and the Daughters of the American Revolution for their work preserving the stones.”

Neither the National Park Service nor DDOT returned requests for comment.

“It’s unfortunate, because the Boundary Stones are our oldest national monuments,” Anderson said.

“So many people don’t know about them. … The more you educate the public, the more they realize what treasures they have, literally in their city — surrounding the city. It’s a treasure and it’s a treasure that needs to be kept.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to include a statement from D.C.’s Office of Planning.