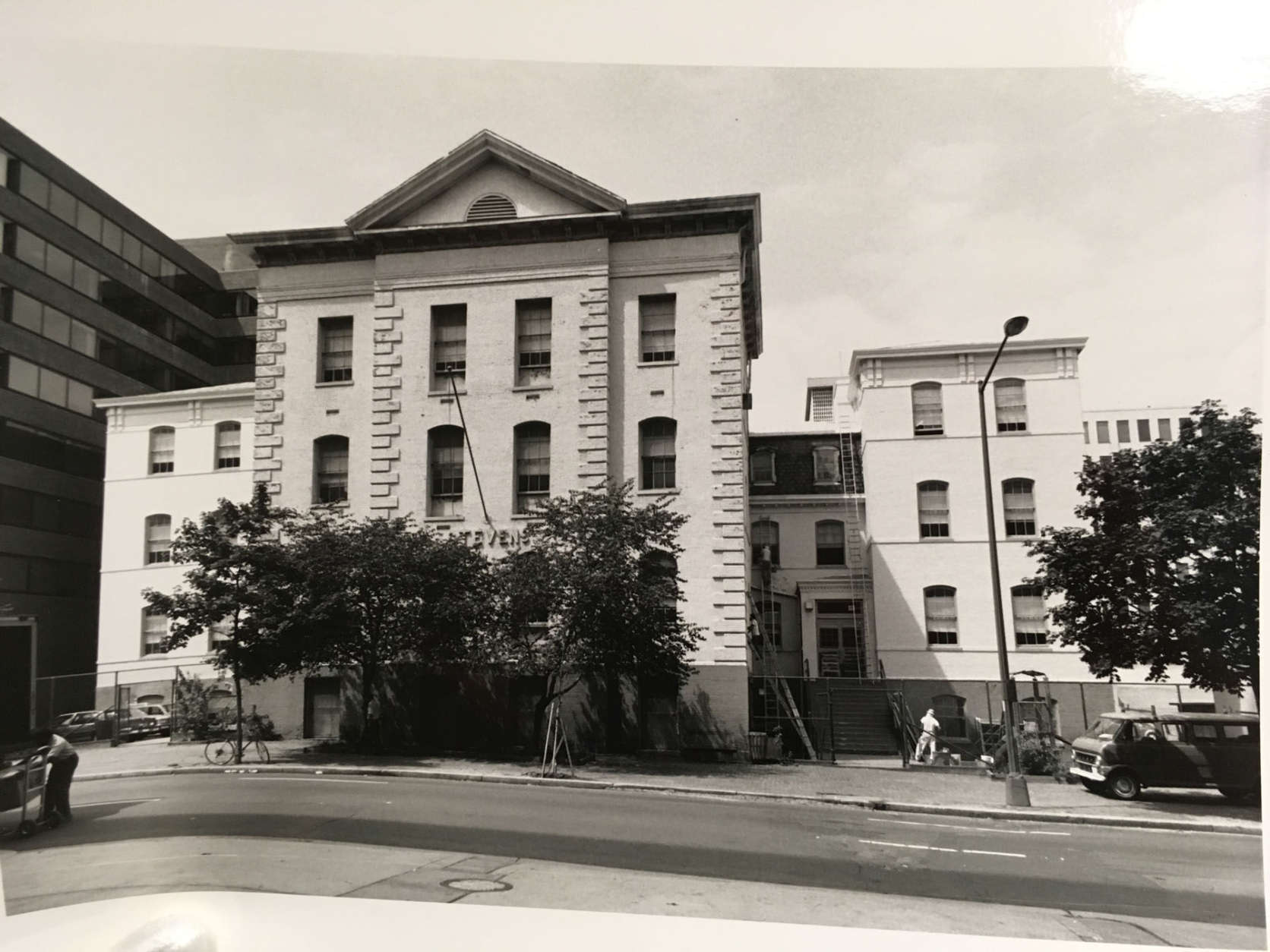

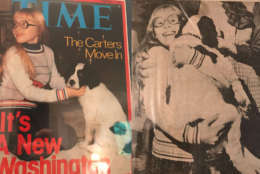

WASHINGTON — In January 1977, the 9-year-old daughter of newly inaugurated President Jimmy Carter started classes in a three-story brick school in downtown D.C., improbably nestled between a maze of concrete-and-glass office buildings.

This was no posh private school.

While the children of high-ranking Washington officials customarily attended leafy, cloistered institutions in the District’s toniest enclaves, Jimmy Carter and first lady Rosalynn Carter took a different path: public school.

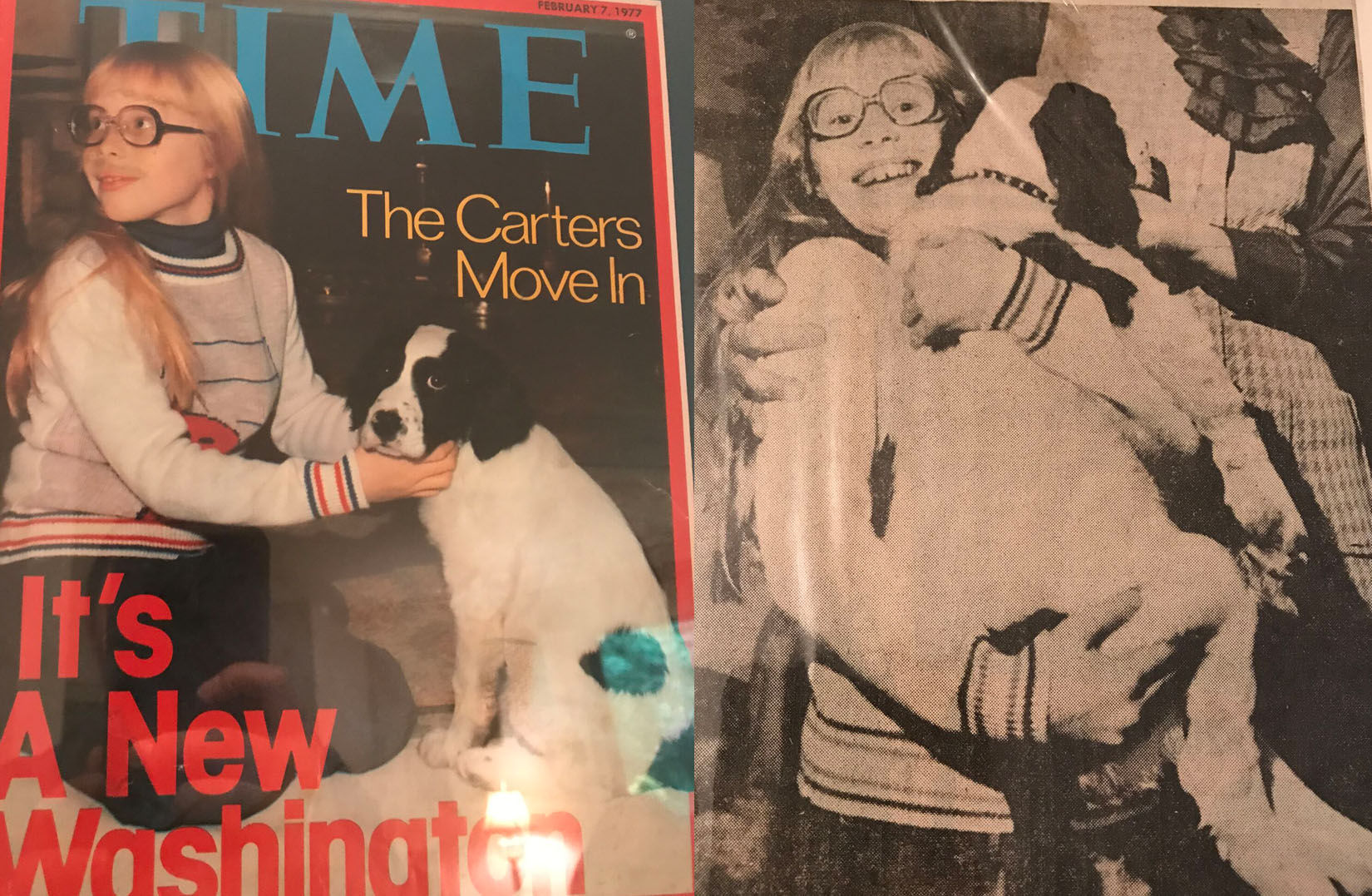

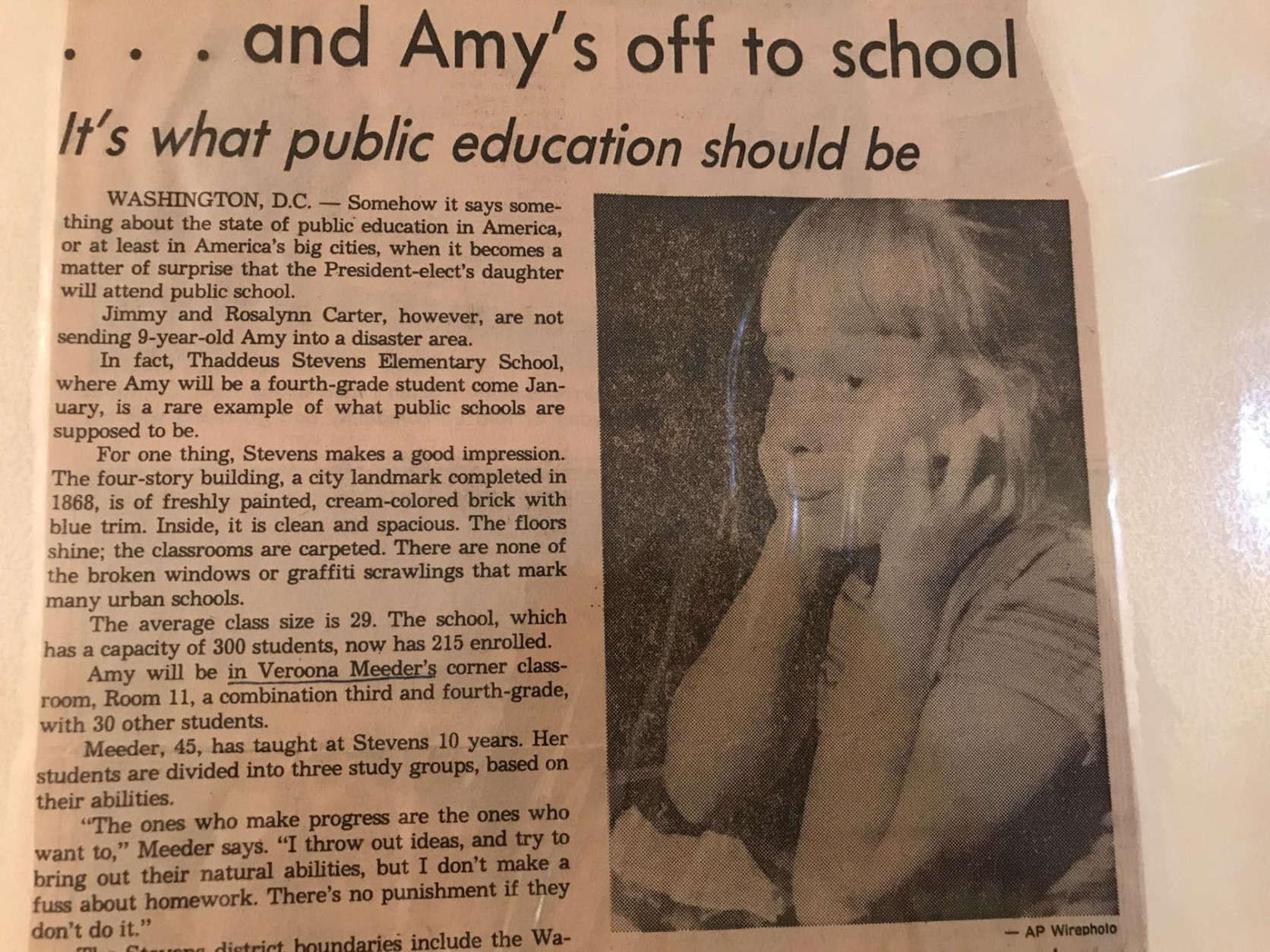

The Carters’ decision to enroll Amy in the Thaddeus Stevens School — a historic African-American public elementary school whose attendance zone the Executive Mansion just happened to fall in — became the subject of intense media scrutiny.

After all, only one other president — Theodore Roosevelt in 1902 — had ever sent a first child to public school before. (And no president since, including fellow Democrats Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, has emulated Carter’s decision).

President Donald Trump is also taking a page from the establishment playbook. His administration announced in May that his son, Barron, will attend the nearly $40,000-a-year St. Andrew’s Episcopal School in Potomac, Maryland, this fall.

With Barron Trump beginning his own unique back-to-school moment next month, WTOP is revisiting the fascinating history behind the D.C. public school that opened its doors to a president’s child 40 years ago and the pioneering educators who made it happen.

The Carters’ choice of schools turned modest Stevens elementary into one of the most famous schools in America seemingly overnight. But by all accounts, the president and first lady were not interested in making a splash.

“The Carters were just nice everyday kind of people,” recalled Jane Jackson Harley, the longtime school counselor at Stevens, now 79, in an interview with WTOP.

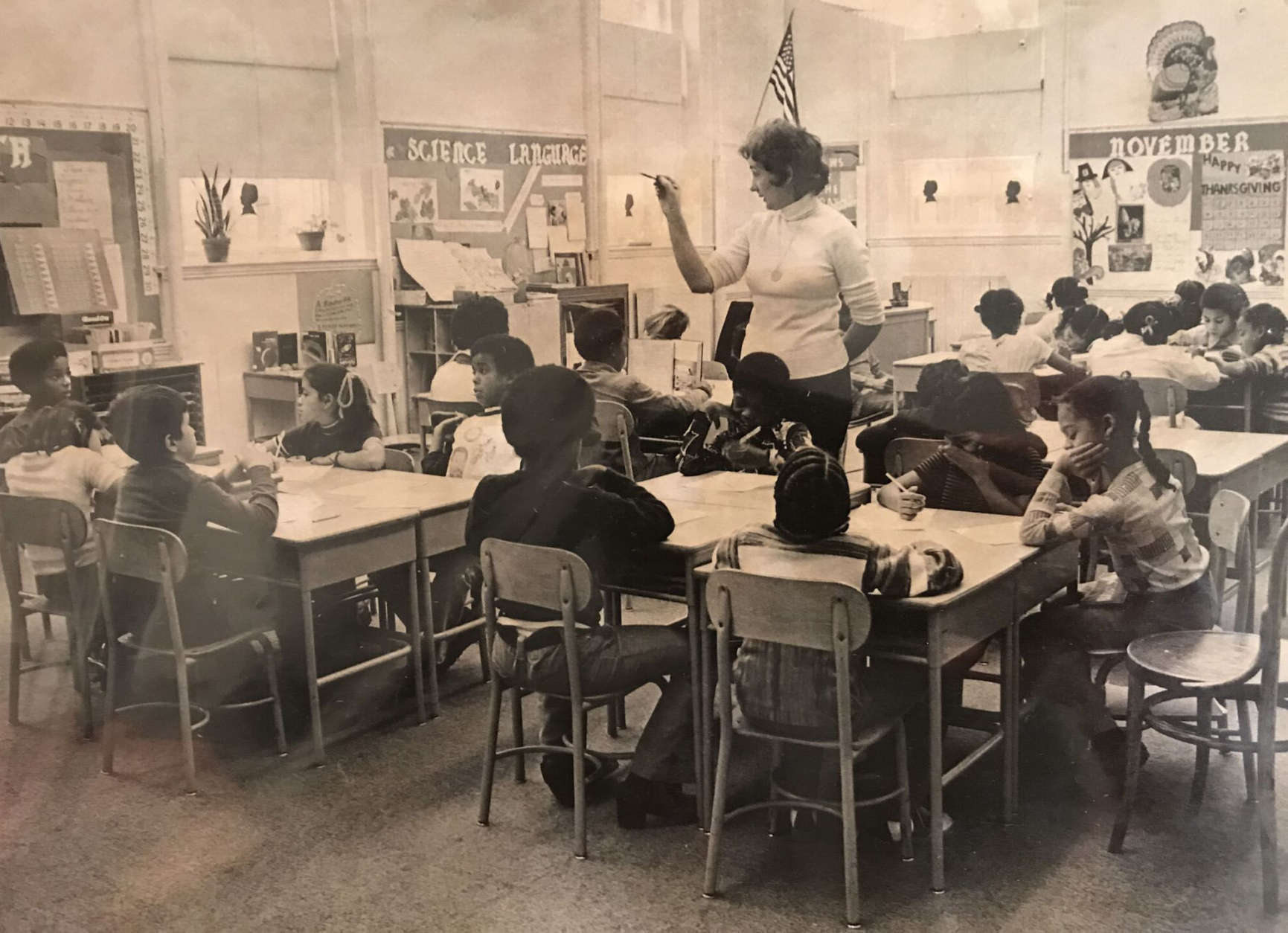

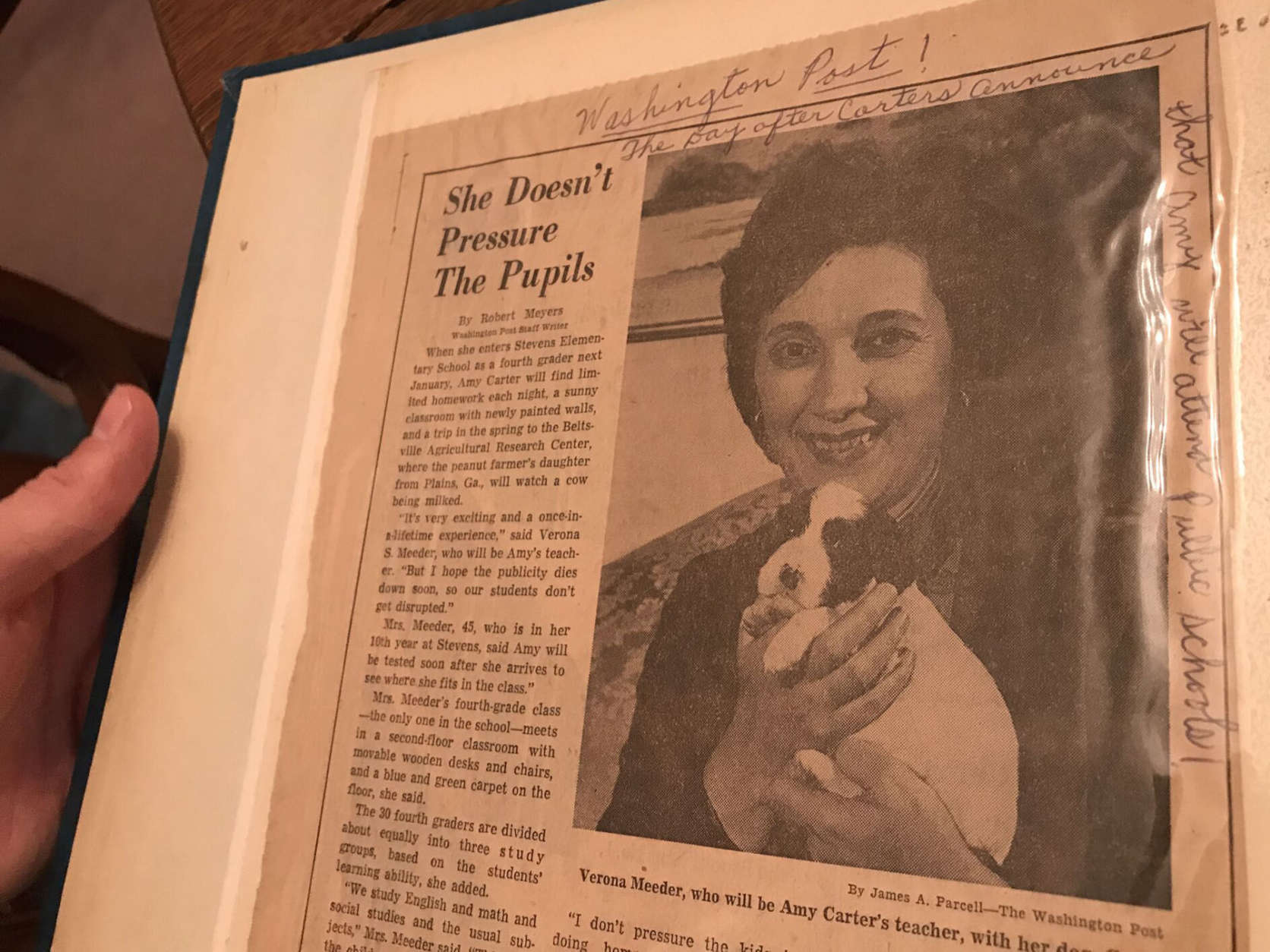

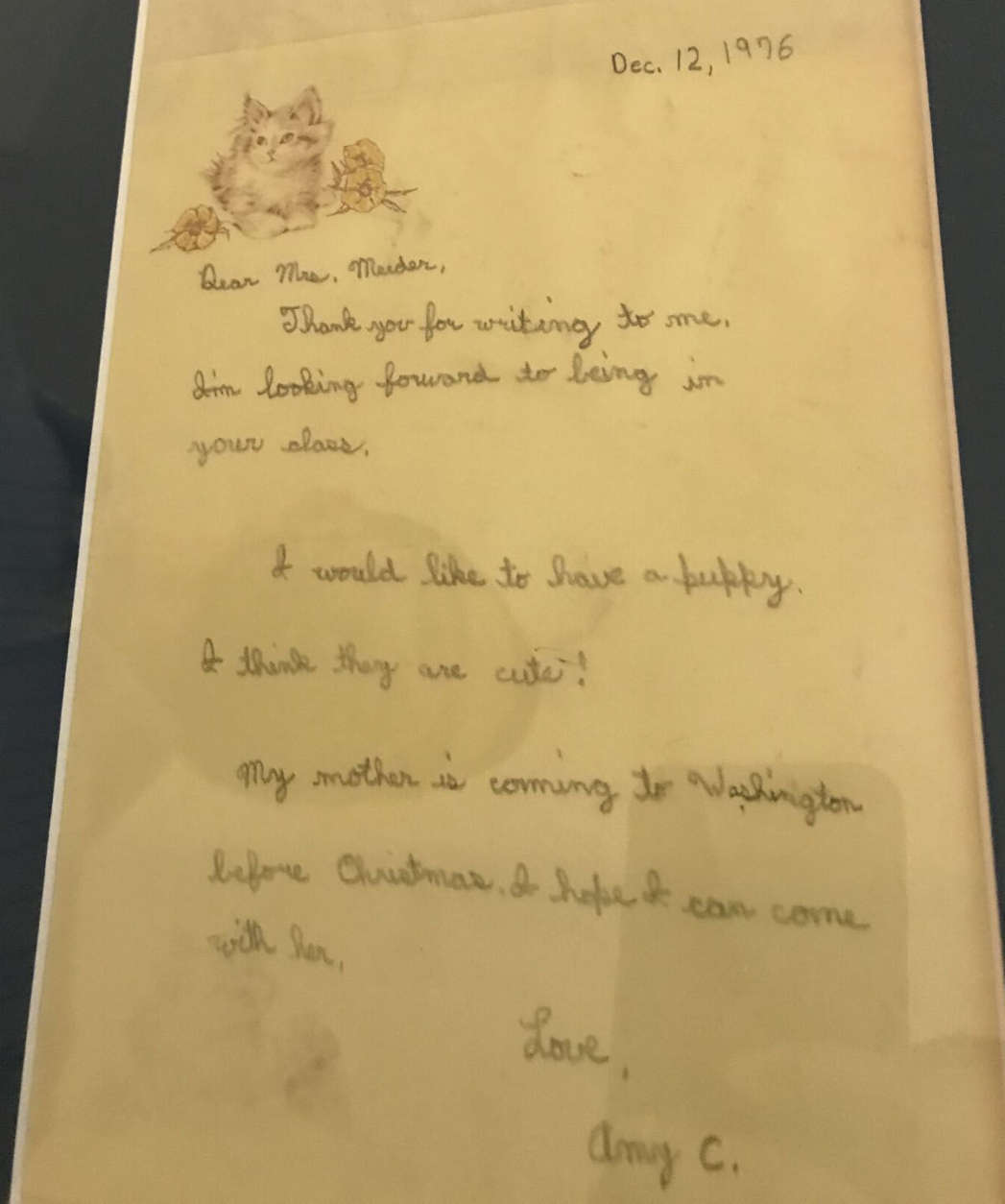

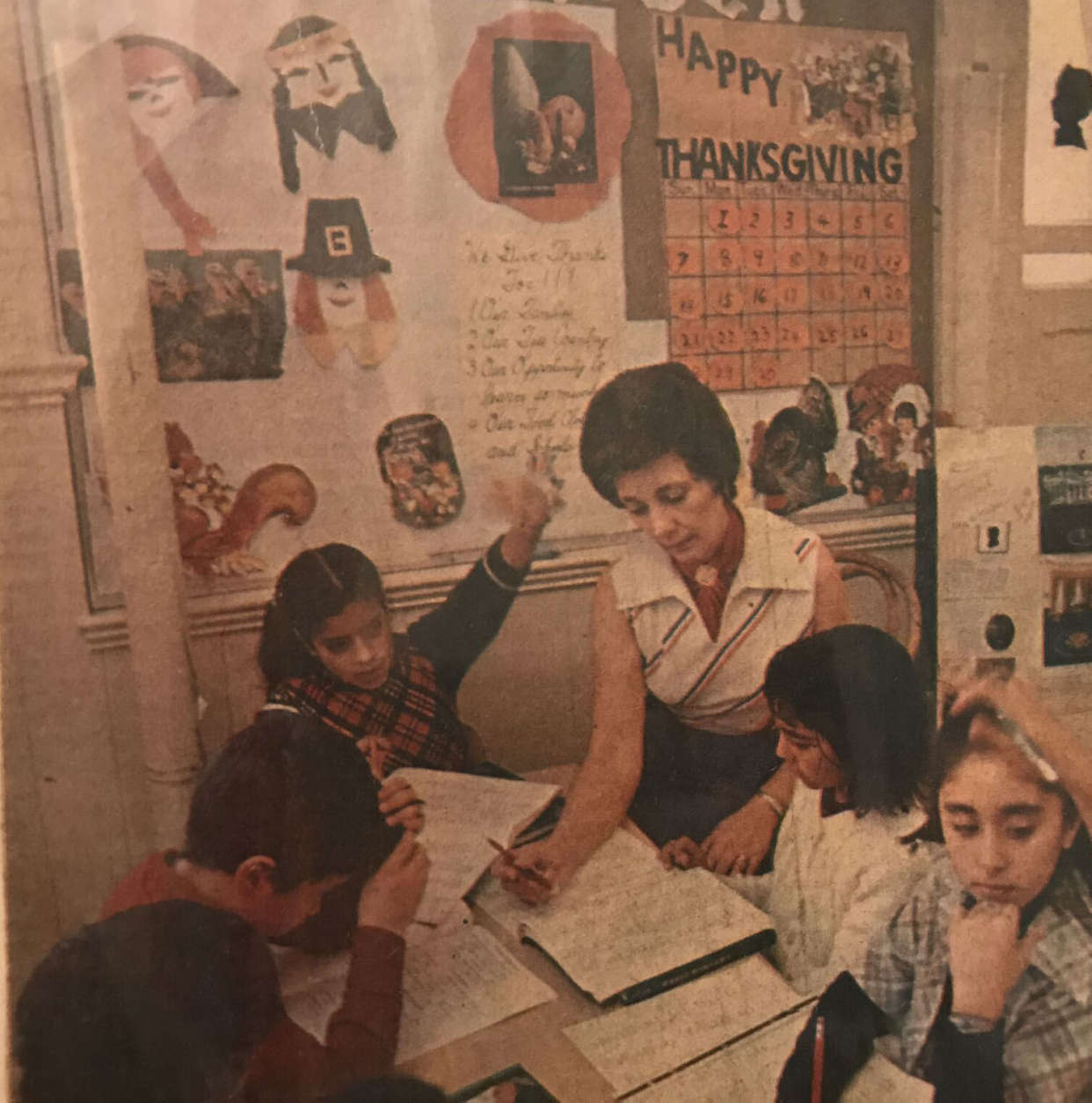

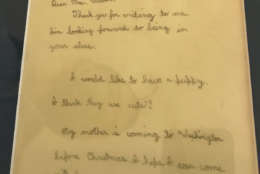

Fourth-grade teacher Verona Meeder recalled an after-school White House visit the day Amy joined her class at Stevens. Just treat her like any other student, the president told her. And if she gives you any trouble, you give me a call.

“To me, it seemed like just another family moved into the area,” Meeder, now 86, told WTOP.

At first a frenzy, but ‘Amy made it feel normal’

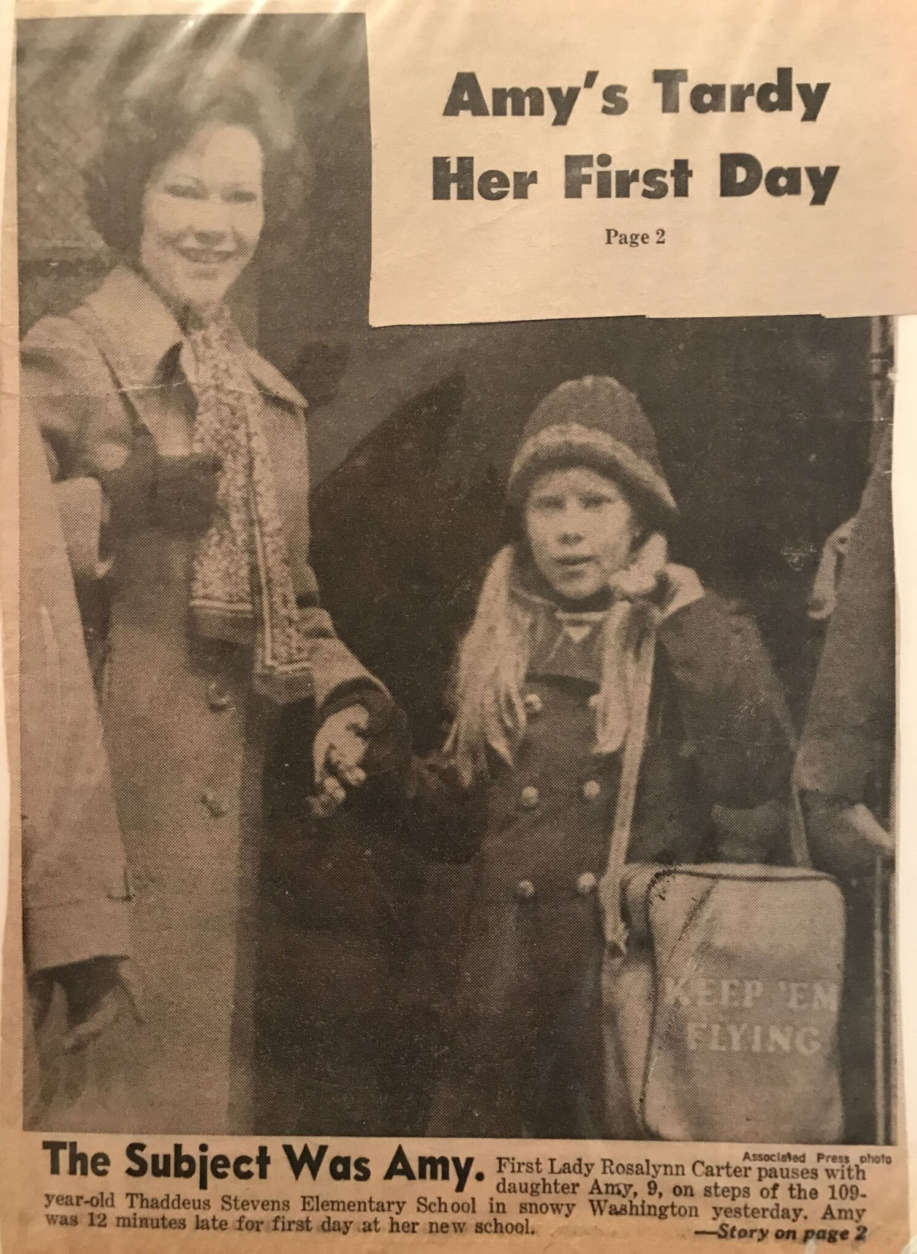

The first day of school for a new student usually brings at least a few jitters. In this case, it also brought a Secret Service detail and a crush of TV and newspaper reporters.

Photographs and video of Amy’s first day of school, just a few days after her father’s inauguration, show a pensive girl in jeans and a stocking cap walking past a rope line of furiously shuttering cameras.

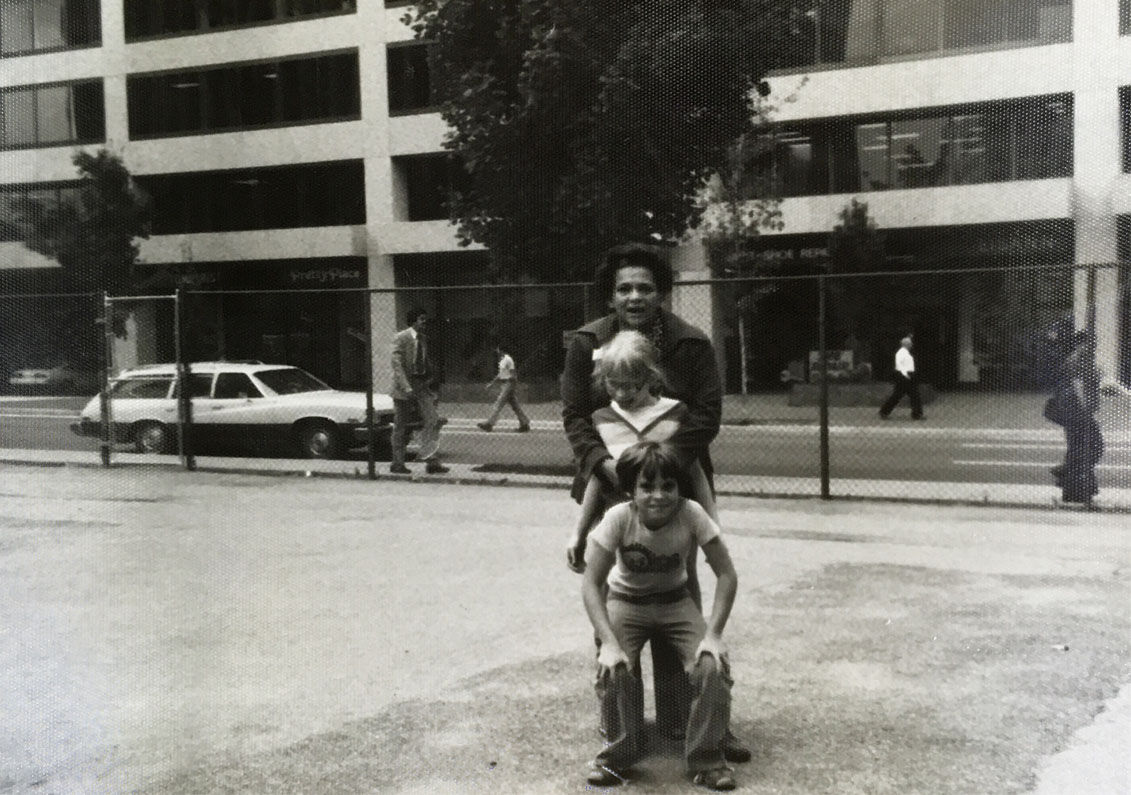

“It was like the red carpet at the Grammys,” recalled Juan Herron, who was then a third-grader at Stevens.

During those first few weeks, reporters covered school field trips and the cafeteria’s lunch menu, and tour buses filled with sightseers crawled past the school aiming to catch a glimpse of the blond, bespectacled 9-year-old at recess.

But things eventually settled down.

“We probably didn’t understand the significance of that being the president’s daughter — even though we knew who she was,” Herron, now 49, recalled.

She was just Amy.

“Amy made it feel normal, because she would do her work and then read her book,” Meeder said. “She always had a book on the corner of her desk. She never asked me what she could do. She just read.”

Other teachers describe her as a quiet, unassuming fourth-grader.

“Amy was very, just, normal,” recalled Rebecca Medrano, who taught Spanish for an after-school program at Stevens. “She was … not somebody who was going to be in your face and talk about being the president’s daughter. It wasn’t that important to her. There were other things she was thinking about — you know, being a kid.”

A kid trailed by two Secret Service agents at all times.

The agents even turned a second-floor closet next to Meeder’s classroom into a makeshift office to watch the comings and goings. But they gave the first daughter space in the classroom.

“At first, I wasn’t aware of them,” Medrano said. “And I was like, ‘This is strange.’ I thought I would’ve had to go through a high-security clearance. Here I am taking a piñata in; it could’ve had a bomb, you know!”

Amy made friends easily, inviting some to slumber parties at the White House. In fact, she seemed to get along with everyone, even the bullies.

“There’s a whole lot of mean boys in this school,” Herron, an 8-year-old on the school safety patrol, told a Washington Post reporter in a June 1977 article. “But nobody messes with Amy.”

‘We were about to close down’: History of a historic school

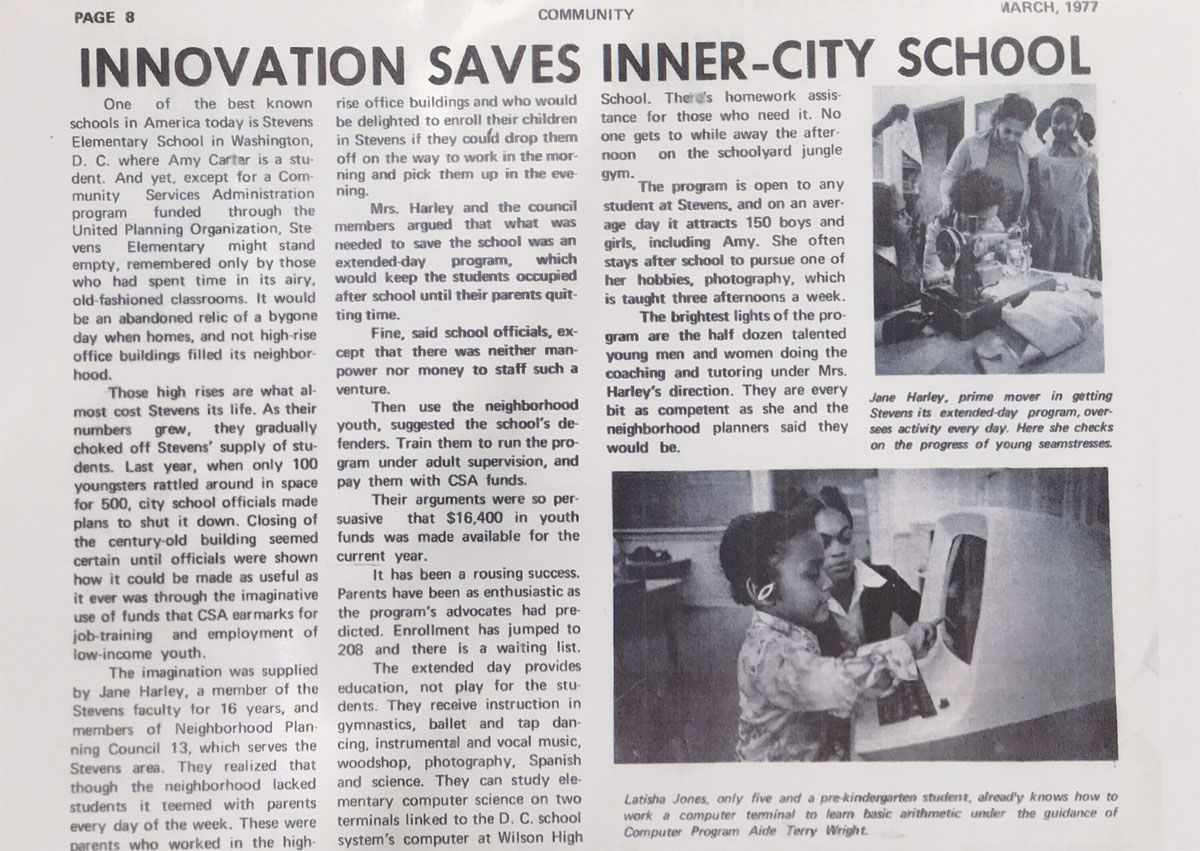

Aside from the roaming Secret Service detail, the most abnormal thing about the school may have been the late hours it stayed open thanks to an innovative “extended day” program.

The program — the first offered at a D.C. school — allowed parents who worked late in nearby office buildings to drop off their children early in the morning for a hot breakfast and pick them up as late as 6 p.m. in the evening.

Today, such extended-day programs are common in urban school districts. In D.C., 30 public schools currently offer extended hours. But back then, such a program was unique. “I should’ve trademarked the name,” said Harley, the school counselor who developed the program.

Amy, who arrived several months after Stevens’ program rolled out, stayed late most days to take part in the extra classes, which included photography, computer lessons and Spanish.

Harley said she wasn’t necessarily trying to be cutting edge. She was trying to keep the school from closing its doors.

“We were having problems keeping the school open because there were no children in the area,” Harley said. “We were about to close down. We were in trouble.”

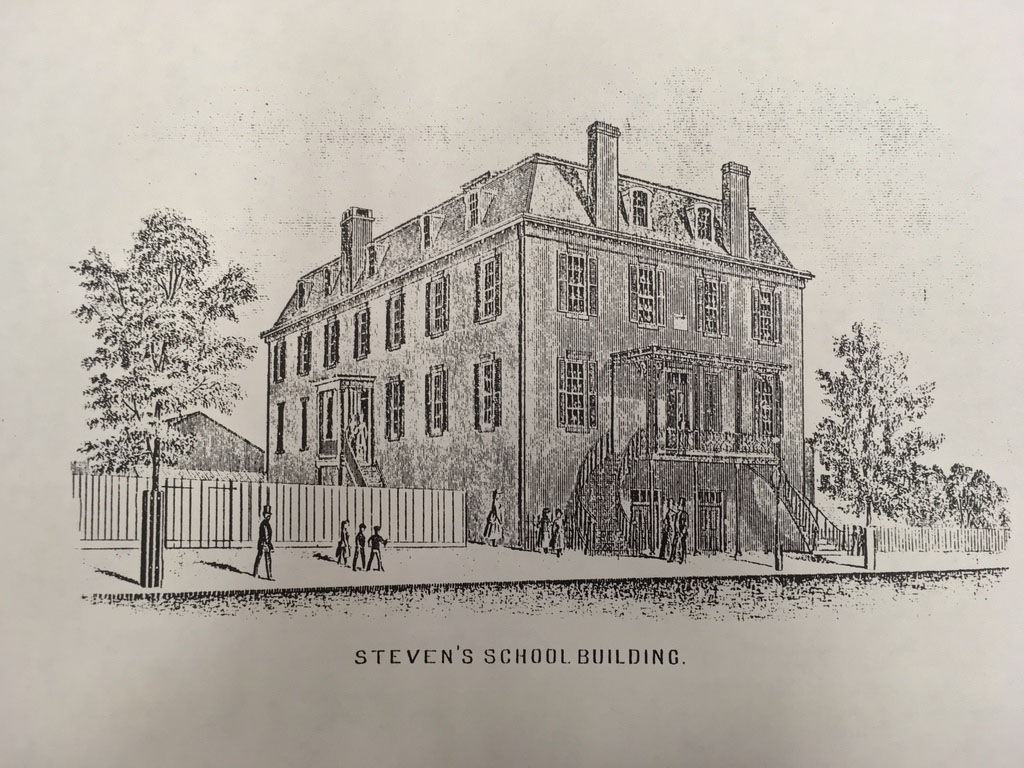

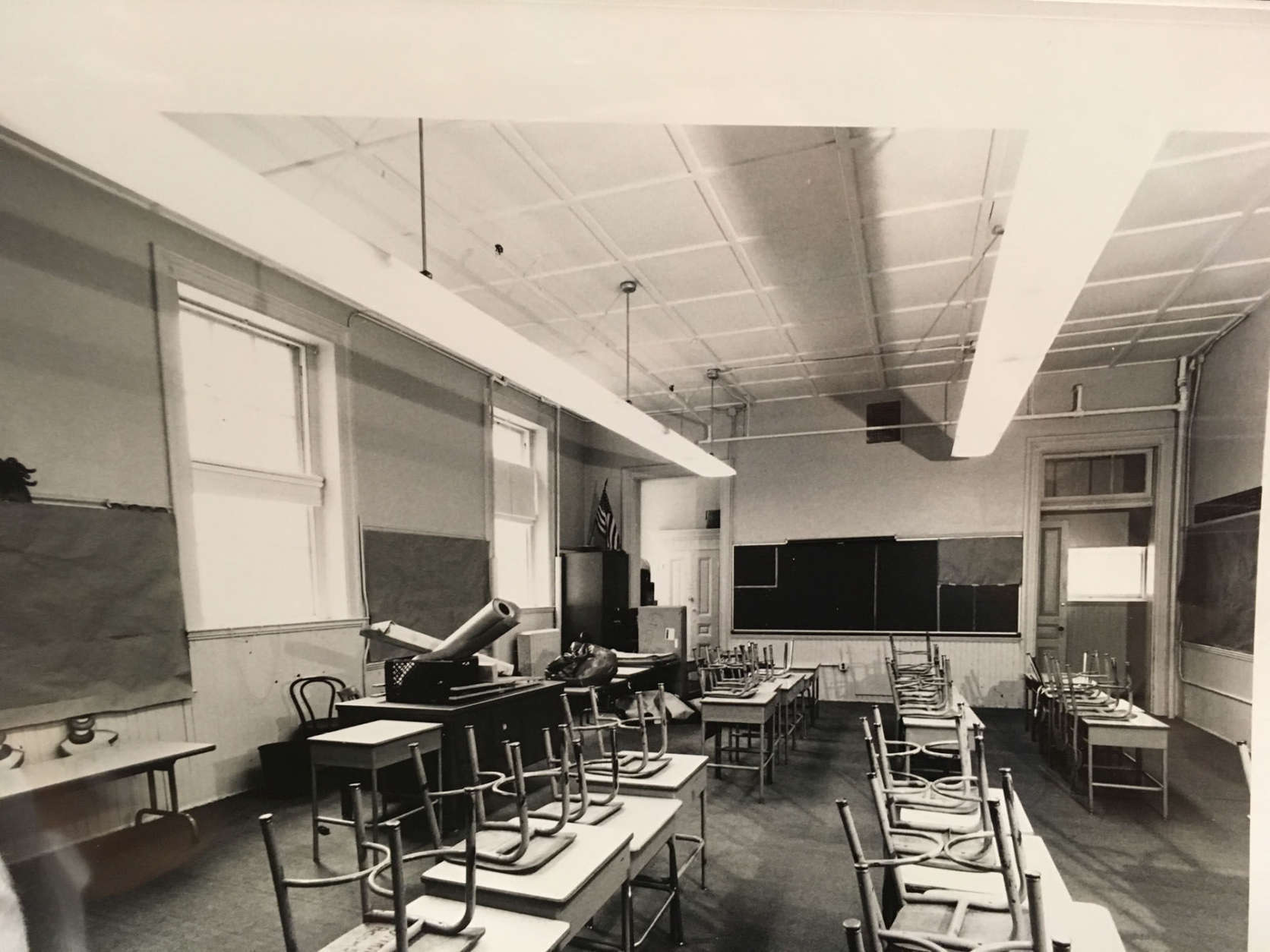

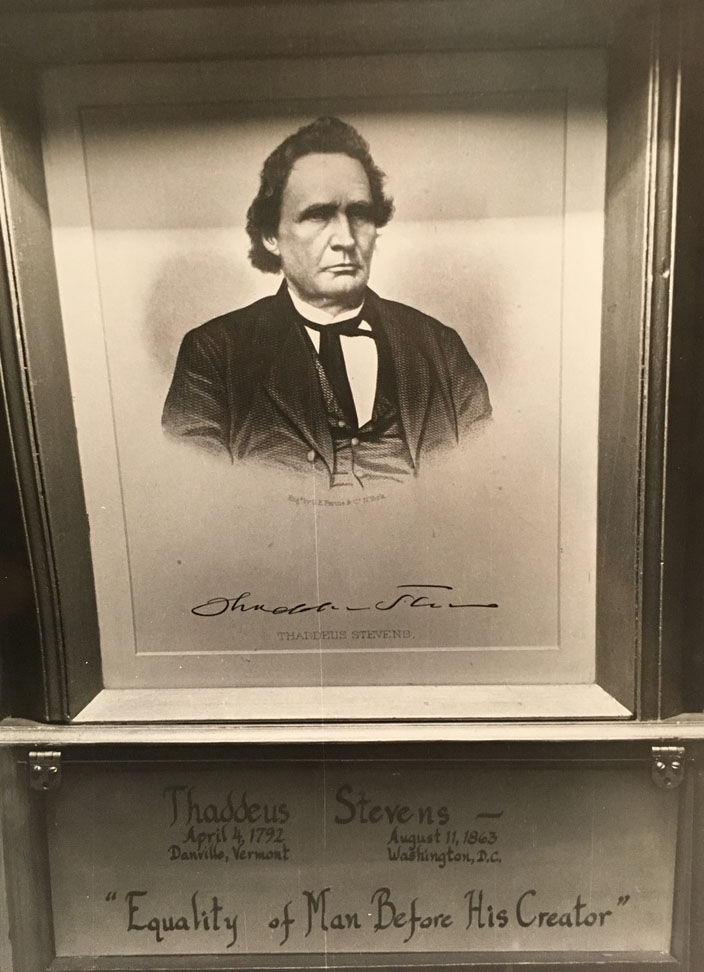

The school had once been the cornerstone of D.C.’s historically African-American West End community and a symbol of progress and achievement. Constructed in 1868 and named for the crusading abolitionist Senator Thaddeus Stevens, the school was the first in D.C. built with public funds to educate black children. Opened amid the height of Reconstruction in the South, its classrooms swelled with students as D.C.’s population surged with the migration north of newly freed slaves.

But by the 1960s, the tectonic plates of gentrification began to shift, and the neighborhood’s row houses and modest dwellings were razed to make way for office buildings and parking garages.

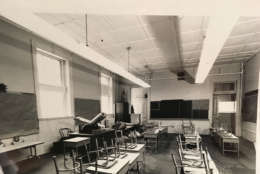

By 1976, the area surrounding Stevens “had become virtually an asphalt neighborhood,” according to a 1980s-era oral history of the school on file at the Charles Sumner School Museum and Archives.

Harley’s extended-day program turned the historically African-American neighborhood school into a sort of magnet school for the children of downtown office workers, and it boosted enrollment back into safe territory.

“The enrollment went up. … It just zipped, especially when they heard the president’s daughter was there,” Harley said. “That was it. The school was saved.”

And having the president’s daughter signed up for D.C.’s first extended school-day program did have its perks.

When red tape threatened the program during its second year, parents packed a school meeting with the D.C. official responsible for doling out funding. One concerned mother in attendance: Rosalynn Carter. Within two days, funding was sorted out, according to a March 1978 Washington Post article.

A political stunt? ‘The Carters were not those kind of people’

The intersection of presidential privilege and a historically black public school could’ve been tricky territory. A few years earlier, President Richard Nixon’s 20-something daughter, Tricia, courted controversy attempting to “do something constructive,” when she tutored two black schoolchildren at the White House.

At the time, D.C. school board member Julius Hobson blasted the seemingly well-meaning gesture as “welfare colonialism,” and told a reporter: “I’m going to find out who in hell gave permission for her to take two black children from the school system.”

Did parents and teachers think the Carters’ choice to send Amy to a predominantly black school was a political stunt? No, Harley said. “The Carters were not those kind of people,” she said.

Many parents and teachers saw it as Carter living up to his ideals.

During his acceptance speech at the 1976 Democratic National Committee, Carter denounced the political elite who, from afar, shaped decisions that affected other people’s lives. “When the public schools are inferior or torn by strife, their children go to expensive private schools,” he said.

Not that quiet Stevens Elementary was torn by strife, but Carter wanted to be clear: Public school was good enough for a president’s daughter.

Still, Amy was living in a mansion down the street while about a third of her classmates qualified for free lunches.

Medrano recalled a tense exchange one afternoon during Spanish class. “Some kid was talking about: ‘Oh, well, Amy has a pool because she’s the president’s daughter. She’s just got everything. And we don’t have anything.”

Medrano sat the other students down for a discussion. “She’s just like you,” she told them. “This is not about being rich or being the president’s daughter. This is a program for all of you. And everybody’s special, not just Amy.”

But being a classmate of Amy Carter’s did come with some special opportunities, including a memorable field trip to the White House for the whole class for its very own Easter Egg Roll. The White House chef grilled up hot dogs and hamburgers. Later, Amy and her classmates roamed the grounds for a hands-on tour of her treehouse hideaway near the White House’s West Wing.

A photo in Meeder’s collection of scrapbooks captures the moment Amy and her Stevens classmates gathered for a class photo on the south lawn of the White House.

Amy’s off to the side — she always shunned center stage — grinning into the glare of the April sunlight alongside her classmates. For at least that day, just another Stevens student.

Where are they now?

Amy Carter transferred to a D.C. public middle school — Rose Hardy Middle School — after two years at Stevens. After her father left the White House in 1981, she moved back to Georgia, attended Brown University, got arrested protesting the CIA and, eventually, got an art degree. She married in 1996 and has a teenage son. Famously press shy, she rarely gives interviews and, through a representative for the Carter Center, declined to be interviewed for this article.

Herron, the 8-year-old on the school safety patrol, went on to join the Marines and served during Desert Storm. Now, 49, he lives in D.C.

A few months before she was hired to teach Spanish for Stevens’ extended-day program, Medrano, along with her husband, founded a small theater company out of their row house in Adams Morgan. They focused on featuring Latin American performers and playwrights. Now working out of a lavish space in the restored Tivoli Theater on 14th Street in Columbia Heights, GALA Hispanic Theater is one of the premiere Latino theaters in the U.S.

Harley, the counselor who spearheaded the extended-day program at Stevens, retired from the D.C. schools in the 1980s after an injury. The daughter of legendary radio DJ and concert promoter Hal Jackson, she went back into the family business, taking up as a talent scout and helping shuttle performers from the D.C. area to the famed Apollo Theater in New York. Among her discoveries: a teenage Dave Chappelle, whom she accompanied on his first stand-up gig at the Harlem theater.

Meeder, 86, lives in Columbia, Maryland, at the end of a quiet cul-de-sac. She retired from teaching in 1992 after 25 years of teaching in D.C. public schools, all but one of them at Stevens.

Stevens Elementary still sits near the corner of 21st and L streets in downtown D.C. But it hasn’t seen any students strolling its halls for nearly a decade. And it’s now facing an uncertain future.

Perpetually bedeviled by low enrollment, Stevens officially closed in 2008 — a victim of then-schools chancellor Michelle Rhee’s controversial school reforms. Its student body merged with nearby Francis-Stevens middle school.

After years standing vacant, the D.C. Council in 2014 approved a nearly $20 million plan allowing developers to renovate Stevens and to build a new 10-story “trophy-class” office on its playground.

But a plan to move a private special-needs school into the building fell apart earlier this year.

At a community meeting last month, an official with D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser’s office told community leaders that reopening Stevens as a public school is now the mayor’s top choice for the historic site.