WASHINGTON — Sunday’s final D.C. United game at RFK felt different than other goodbyes.

This wasn’t the final day of the Senators, with fans storming the field in protest of the team leaving town. It was closer to the ‘Skins or Nats, making long-awaited and promised moves across town. But the day was steeped in the knowledge that this was really a goodbye to the building itself and the culture cultivated within and without its walls, and the uncertainty of what it all will look like in the future.

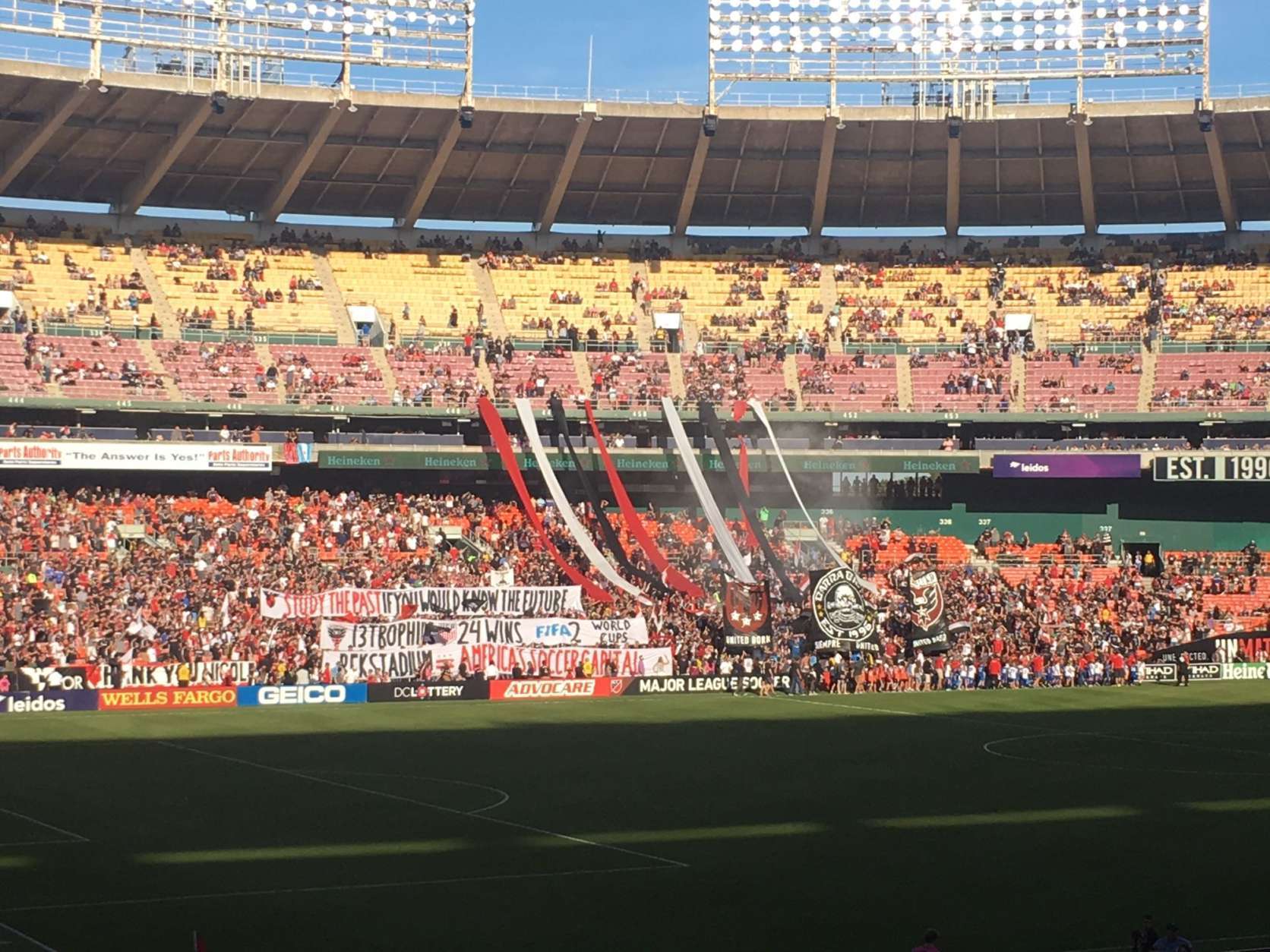

The sun set on RFK Stadium both literally and figuratively Sunday as the Red and Black took the field for the final time at 2400 East Capitol St. SE. It was a day to remember that a crowd of 41,418 was still possible for a United game here, and also that it had been ages since they had needed to open the upper deck. It was a time to remember once again how much you hate the Red Bulls, just for being the Red Bulls.

There was one last tailgate and a legends game, featuring the greatest players in the 22-year history of the club. That made the day primarily a celebration of the past, of what has been and what used to be. The success of those championship teams feels a far cry from the current state of affairs, where United finished the year dead last in the league. But the tailgate itself only came to an end Sunday.

The Lot 8 tailgate was inclusive in a way that much of the city often isn’t. Black, white, Latino, young and old, single partiers and generations of families. Everyone shared in that experience together, from the graying, original fans who have done this for more than 20 years to the next generation, kids kicking around soccer balls sporting Screaming Eagles jerseys three sizes too big, swallowing their frames and nearly covering their knees.

In the middle of it all, as he’s been for all but about 40 games over the last 22 years, was David Ivey-Soto, frying up enough quesadillas in his scalding steel cauldron to feed a small army. Often, he would make food to correspond to the opponent; chowder for New England, cheesesteaks for Philadelphia. He made quesadillas instead of his usual for the visiting Red Bulls, who he still refers to by their actual geographic home.

“Every time we played New Jersey, I would do turkey,” he said, a smile peeking out of the corner of his mouth as he flipped a batch of quesadillas. “Because they’re a bunch of turkeys.”

Ivey-Soto says he hasn’t had any formal conversations with ownership about what happens next year at Audi Field, but he’s hoping to figure out a way to keep the tradition alive.

“If we can, we’ll do it.”

There will surely be a drumline, still, when the team and its fans converge on their new home in Buzzard Point next spring. Many of the faces will be the same, and hopefully many of the traditions. But there won’t be the tunnel under East Capitol Street, the 80 feet of semi-cylindrical steel where that sea of noisemaking stops and reloads, like a hurricane stalling out before charging onwards. There won’t be that perfect geographical and acoustical convergence of the space that connects Lot 8 to the stadium, a catch trap of chaos and frenzy that encompasses as much of the D.C. United fandom and culture as anything else.

As the fans filed in, the late-afternoon sun shone brightly enough on the white “1 match left at RFK Stadium” banner to see the red and black lettering reading “Audi Field” underneath. It was the prism through which every aspect of the day was refracted, a backward glance over the shoulder at the past as your feet moved one in front of the other, ever forward.

The final rendition of the national anthem was sung by one Dwight Clyde Washington (D.C., as you probably know him), because who else would you possibly ask to do the honors for such an event? One can only imagine we’ll see Washington again next spring to open Audi Field, a bridge of the gap between the past and present of soccer in D.C.

By the start of the game, most of the field was in shadows. Only the supporter groups that fill the East half of the lower bowl and make it sway for 90 minutes remained draped in the sunlight. When D.C. United scored late in the first half, the celebratory beer showers were still soaked in sunshine. By the time New York tied the game in the 68th minute, then pulled ahead shortly after, everyone but the upper bowl interlopers were in darkness.

The match meant nothing in the standings to either club, with United long since eliminated and New York locked into the sixth and final playoff spot in the East. But you wouldn’t know it from the cheer that went up when Steve Clark saved what seemed the likely nail in the coffin, a penalty with less than 10 minutes left, on a headlong dive to his right. That, at least, meant drama to the end, something to yell and chant and wave the flags for in earnest all the way to the final three whistles.

Ben Olsen — game over, season over — nevertheless aired out the officials over their inconsistencies all the way to the tunnel before doubling back to give the crowd a final round of applause.

“It’s been an emotional day,” he said after the postgame festivities. “You know, the loss hurts. There’s nothing more frustrating than to not give these fans a win after they put that type of crowd and energy.”

The game itself mirrored the final season at RFK: A glimmer of hope in the form of a goal produced by the core duo of Acosta and Arriola; the frustration of a year lost, through Acosta’s questionable straight red card; the quieting disappointment of a come-from-ahead loss on the strength of two late New York goals.

“It’s a little bit of how the year’s gone for us,” said Olsen.

The question of what next year will look like on the field depends on a number of factors, but it will certainly be different, given the departure of goalkeeper Bill Hamid. The first player signed out of D.C. United’s youth academy, the Annandale, Virginia, native will step into his own new world next year, in Denmark. His stalwart goalkeeping has anchored much of the Black and Red’s success the past few years, but next year’s squad will have to find a way without him.

But the difference of the field itself will be the greater one. Whatever Audi Field is, it won’t be this faded, cracked, dying bowl of memories. To argue whether it will be better is to miss the point. It will be inexorably different, but capturing as much of the cacophonous, rowdy, grimy charm of RFK as possible will be as instrumental as anything in making sure what was built within these concrete walls lives on.

It won’t have a press box that wobbles with the energy of the stadium, making you laugh and joke and, when it really starts to shake, secretly fear for your life. It won’t have the WiFi cutting in and out — mostly out — in that press box, from which the public address system is muddled enough to only make out every third word or so.

And sure, Audi Field will be great. Of course it will be. It’ll be new; it’ll sparkle and shine with clean steel beams not subjected to decades of D.C. humidity, with fresh panes of glass; the smells of fancy concessions will fill the air and our heads with second guesses of why we ever deigned to miss a menu headlined mostly by hot dogs, chicken tenders and fries.

It won’t be RFK, for better and for worse.

Walking out from the old stadium for the last time into the fall evening Sunday, arms still warm and ears still buzzing, the thinnest sliver of a crescent hung shining in the after-dusk twilight to the west-southwest, a new moon rising in the distance.