This article was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

This article was written by WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters and republished with permission. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

The federal government’s 1995 decision to allow states to set speed limits higher than 65 mph caused almost 14,000 additional deaths over 25 years on interstates and freeways, according to a new study by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety.

That average of 560 deaths a year ”is really a big deal,” said Charles Farmer, the author of the study and a vice president of the Insurance Institute, which is funded by the insurance industry. However, it’s about 10 percent of what federal officials and some safety advocates predicted in 1995, when they opposed Congress ending the national 65 mph limit.

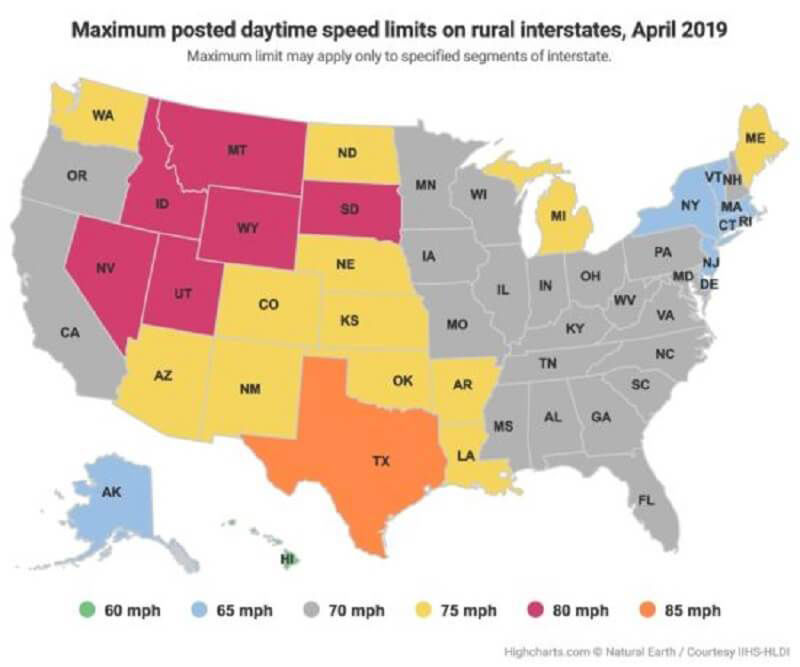

The study maps the speed limits of the 50 states and District of Columbia. It says 41 states now have limits of 70 mph or higher. That includes six states with 80 mph limits and Texas, which allows 85 mph on some roads. Eight other states have limits of 65 mph and Hawaii’s is 60 mph.

There’s a high price to pay for getting somewhere faster, Farmer said.

A 5 mph increase in the speed limit increases the number of interstate deaths about 8 percent, according to the study. A 10 mph hike would increase the number of deaths by 17 percent.

“But it’s actually an exponential relationship, so things start to spread out after that: a 15 mph increase yields a 27 percent increase in fatalities,” Farmer said.

And drivers probably overestimate how much time they save by going faster, Farmer said: Driving 100 miles at 65 mph takes only seven minutes longer than driving at 70 mph.

The study also estimated that higher speed limits have resulted in 23,000 additional deaths on other types of roads — for an increase of 37,000 speed-related fatalities altogether. However, Farmer said that data was “a little bit murky because we didn’t know specifically what was going on with speed limits on those roads.”

Farmer said his work focused on the interstates and freeways because they have the higher speeds, and there is precise information on when and where speed limits changed.

“But there is some carry-over effect. People get used to going fast on the interstate; they may go a little faster on a secondary road, and some of the secondary roads have had their speed limits raised,” he said. “We have seen over many studies that when you raise the speed limit on one road, you also see increases on other roads.”

Speed clearly kills, and hopefully the study will increase the focus on reducing speed-related deaths and injuries, said Jason Levine, the executive director of The Center for Auto Safety, a consumer advocacy group founded by Ralph Nader.

“Speeding has become almost a forgotten issue in traffic safety discussions, and clearly we’re losing any sense of limits,” Darrin Grondel, chair of the Governors Highway Safety Association executive board, said in a statement.

A spokesman for the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration said that while speed limits are controlled by the states, speed is a major concern for the agency.

“For more than two decades, speeding has been a critical factor in approximately one-third of all motor vehicle fatalities. Speeding endangers everyone,” he said.

The rise in speed-related deaths has come at a time when total crash fatalities have dropped from about 40,000 in 1993 to 37,000 in 2017, the years covered in the study.

During that time, safety officials have worked on issues such as drunken and distracted driving as well as making vehicles significantly safer. Design improvements include better protection for occupants in a crash and the ability to avoid a crash thanks to electronic aids that can correct skids, warn of impending collisions and automatically apply the brakes.

States didn’t always have the right to set their own speed limits.

In 1974, Congress set the limit on interstates at 55 mph as a fuel-saving strategy in response to the Arab Oil Embargo.

In 1987 — responding to complaints about the 55-mph maximum — Congress gave states the right to increase the speed limit to 65 mph.

Then, in 1995, Congress got out of the speed limit business, accepting the argument that states should have the right to decide. That decision angered and dismayed some medical and insurance groups as well as safety advocates such as Ralph Nader, who told The Washington Post it was “an assault on the sanctity of human life.”

Speeding is also getting the attention of the European Union. It is working on a plan that — starting in 2022 — could require all new cars to have a device that will warn the driver when the speed limit is exceeded. It has yet to be approved.

Last month, the Insurance Institute and the Governors Highway Safety Association held a conference in Virginia to discuss strategies for controlling speeding.

“Speeding is still a problem,” said Russ Martin, the safety association’s director of policy and government relations. “It’s been a problem for a long time.”

This story was produced by FairWarning, a nonprofit news organization based in Pasadena, Calif., that focuses on public health, consumer and environmental issues. Like Maryland Matters, FairWarning is a member of the Institute for Nonprofit News.