WASHINGTON — Routine sign replacement above an orphaned freeway in Foggy Bottom uncovered a roadside relic Thursday morning, evoking memories of an ambitious and contentious era in highway design.

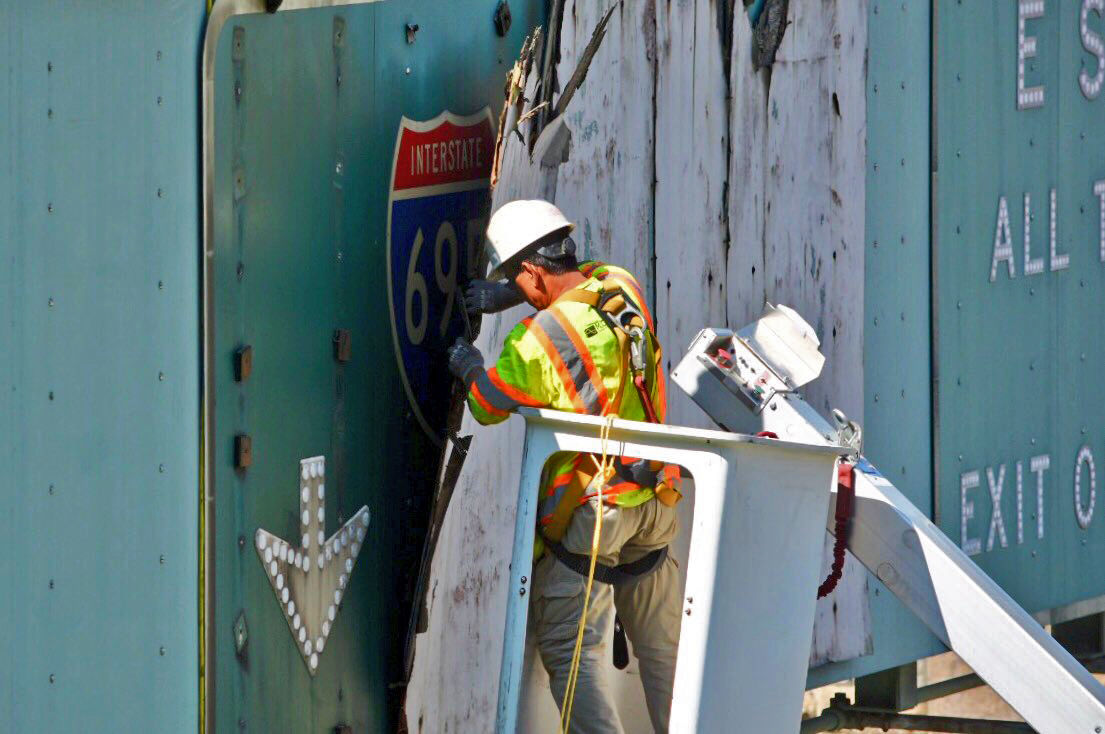

Cones were in place and two left lanes were blocked by 10 a.m. on the Interstate 66 Potomac River Freeway. Road crews with grinder saws and hammers were lifted by bucket trucks up to a weathered overhead structure behind the Kennedy Center.

As strips of rotting plywood were pried off the face of a nearly 50-year-old sign, the outline of an Interstate 695 shield and two white arrows came into view, indicating a freeway that never saw the light of day.

“This sign is going to go to our office and we are going to install it in an area where we can preserve its history,” said Ogechi Elekwachi, citywide field manager for the District Department of Transportation. Elekwachi watched as pieces of the sign were carefully dismantled and lowered into the back of a truck.

“We have people tour our sign shop to see how we fabricate signs, so this is an opportunity to share with them this historical sign,” Elekwachi said.

The green guide sign dates back to a time when a vast, sprawling highway network was slated to carve through the city.

The proposed I-695 South Leg of the Inner Loop Freeway would have linked the Potomac Freeway and the successfully completed Southwest Freeway, presently the city’s busiest road. Although much of the road would have tunneled underground and out of sight, the planned highway was heavily criticized for its proximity to the National Mall and Tidal Basin.

When construction began in 1960, the Potomac Freeway was poised to become a vital link in an interconnected highway network that would encircle the city.

As political and residential opposition to the proposed freeway segments ballooned during the 1970s, plans to merge the road with an upgraded Interstate 266 Whitehurst Freeway and a six-lane tunnel under K Street were abandoned. The tunnel would have routed I-66 from the Potomac Freeway under Mount Vernon Square to the present day terminus of I-395 and the Third Street Tunnel.

Today, the appendage of I-66 in the District courses a mere eight-tenths of a mile under Virginia Avenue, terminating abruptly near the Watergate Hotel at 27th Street Northwest. For this reason, the Potomac Freeway was featured as one of the region’s ghost roads in 2014.

The artifact removed on Thursday harkens back to a time when highway aids were made from different materials. The design style of signs manufactured prior to the 1990s was referred to as button copy. Small reflective discs were pinned to each of the visual elements, increasing their reflectivity when illuminated by headlights.

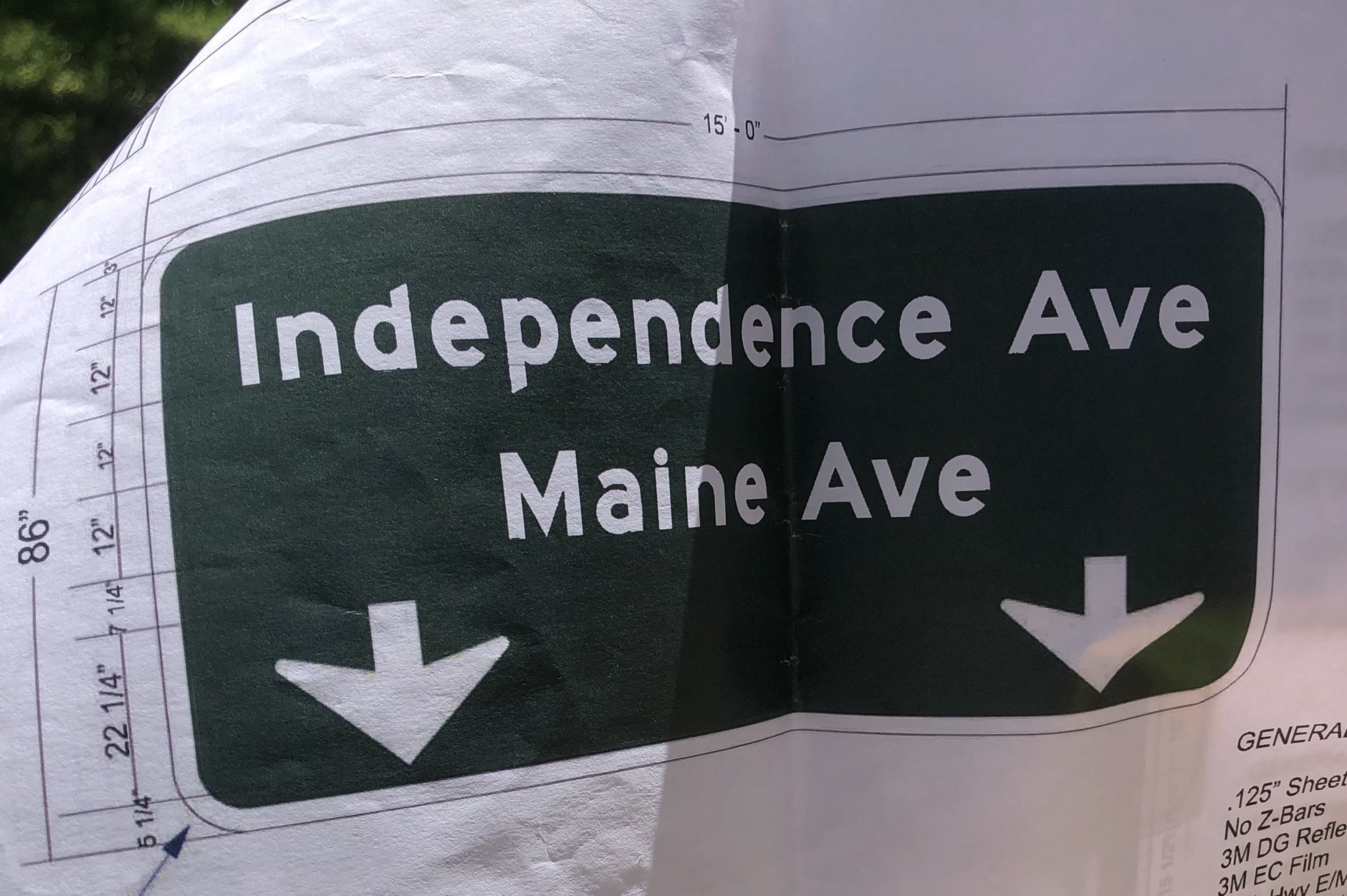

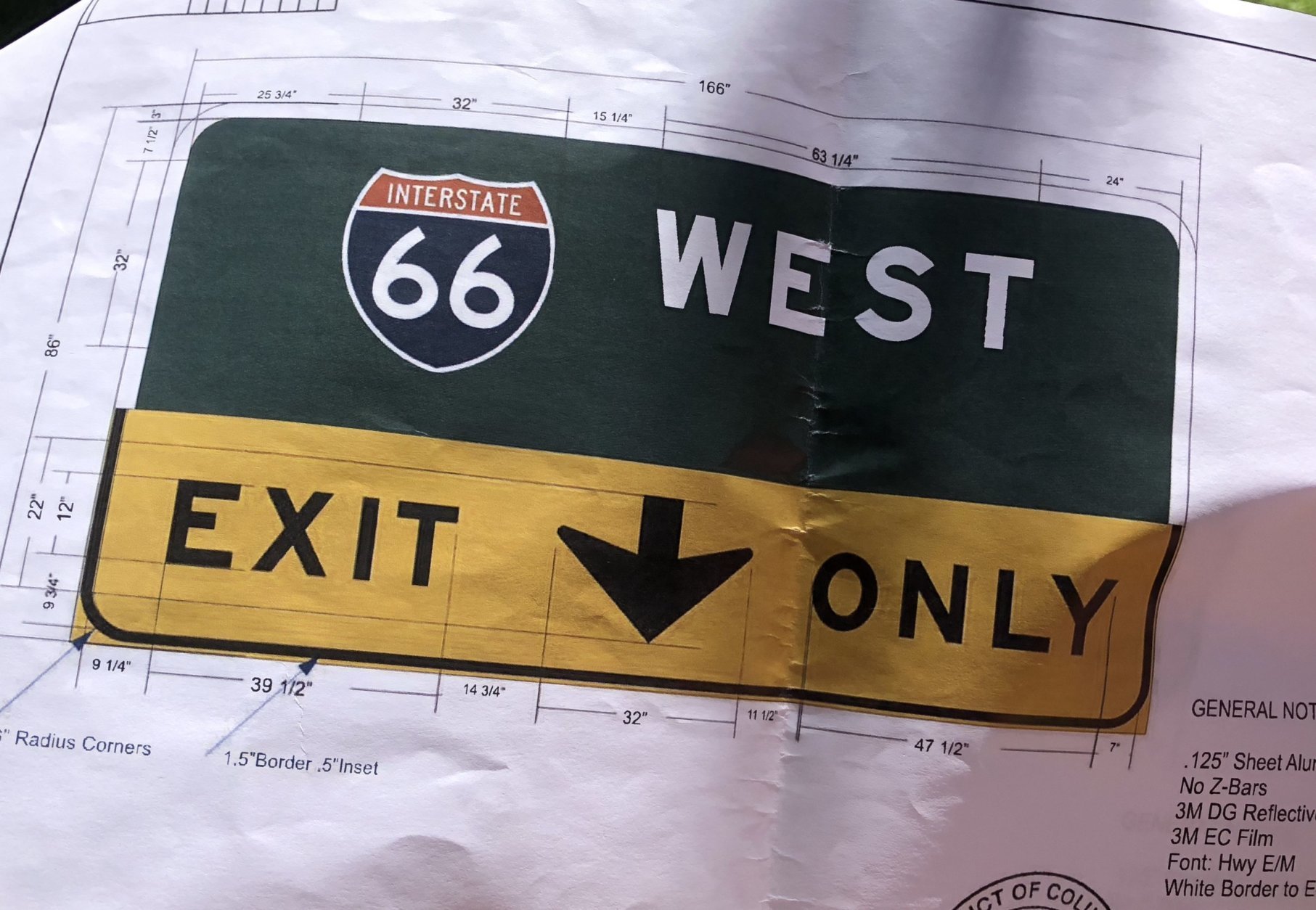

Elekwachi said the three replacement signs for Independence Avenue, E Street and I-66 West will have superior reflectivity compared to their predecessors.

“In terms of the font size, the current [Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices] has a different standard that we have to follow. Also the sheeting material that we use now is a diamond grade for overhead signs.”

Mike Tantillo, a transportation engineer and road enthusiast, was not associated with the work but couldn’t resist stopping by to watch the operation from afar.

“This is a piece of history that has been unearthed almost like an archaeological dig,” Tantillo said. “This is something that has been hidden for many generations and decades.”

Situated in the middle of the structure, the two faded signs for I-66 and E Street have been pummeled by countless snow and windstorms over the years, but Tantillo said sunlight took a greater toll.

“Typically, modern signs have a warranty on the reflective sheeting of about 10 to 15 years, though the “retroreflectivity” of the sheeting could last 25 years under the right circumstances.”

Tantillo, a traffic device expert, said that the signage could have exceeded its life expectancy since it faced north, away from the direct rays of the sun.

“For signs to last 50 years – those are absolutely ancient,” Tantillo said.

The fourth boarded up sign on the right side of the structure will not be replaced. It marked the spot where an old exit used to be.

The off-ramp from the Potomac Freeway to the Kennedy Center was permanently closed by early 2002 when city planners decided to offer drivers an easier way to leave the parking areas. An on-ramp to the outbound lanes of the freeway and Roosevelt Bridge was opened in its place three years later during the summer of 2005.

“Mayor [Muriel] Bowser and [DDOT] Director [Jeff] Marootian are really committed to enhancing safety for everyone that travels our roads so that they know where they’re going and that it’s clearly identified and clearly marked so this project will make sure that the signs on the Potomac River Freeway are updated to Federal Highway standards,” said DDOT spokesperson Lauren Stephens.

Stephens says the agency’s field operations team receives many requests from residents, council members, ANC commissioners and other stakeholders for sign improvements. The Potomac Freeway signage, she said, is “one of DDOT’s most frequent requests.”

The overhead sign work is expected to be completed by Friday afternoon.

A full-scale overhaul of the District’s highway signs could be on the horizon. DDOT recently secured funding from the Federal Highway Administration for a project, currently in a procurement phase, that will evaluate and possibly revamp highway signage throughout the city to ensure compliance with federal standards.

Editor’s Note: The dismantling of the first sign took longer than planned. The District Department of Transportation plans to resume the work to replace the remaining signs on Wednesday, Aug. 29.