FAIRFAX, Va. — Self-driving and connected cars are out on the road with regular commuters in Northern Virginia.

“The great thing about Virginia is the fact that there’s a lot of hands-off from the government,” Virginia Tech Transportation Institute research associate Reginald Viray said Wednesday.

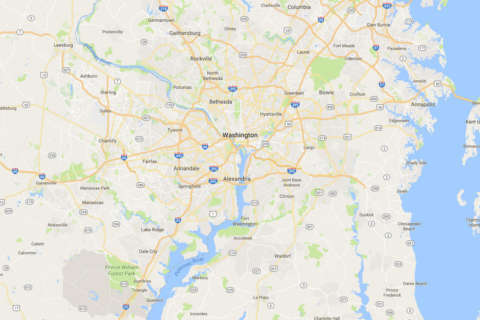

While regulators oversee or issue permits for the tests in other states, Virginia does not restrict self-driving or connected vehicles. Virginia also has designated automated and connected vehicle corridors along part of the Beltway, I-95, I-66, U.S. 29 and U.S. 50 among other roads.

“In Virginia, it’s a little bit more discreet, so companies could test in real-world environments and you wouldn’t even know, so we have some proprietary studies going that route. But we also have some public ones where the general population can take part in some automated vehicle testing,” Viray said.

Fairfax County hosted a demonstration Wednesday of connected vehicle technology that uses short-range radio transmissions built into cars, traffic signals or signs to alert drivers or automated vehicles to any upcoming risks.

The technology broadcasts location, speed and direction data from each car every tenth of a second.

“You won’t see it or hear it unless it detects a warning, and it will just run automatically. It’ll be part of the safety system,” eTrans Systems CEO John Estrada said.

His company, based near Fairfax County’s Mosaic District, was demonstrating its interpretation of the technology, which could be added to older cars to provide safety warnings to drivers with the aim of preventing the many crashes that are tied to driver mistakes such as distraction or speeding.

A warning could also prevent a pileup when someone ahead, but out of sight, slams on the brakes.

Estrada sees low-speed urban areas such as Reston or parts of Tysons as some of the best candidates for initial locations in the region, besides highways, where connected and autonomous cars, taxis or shuttles could get widespread use.

“Highways are fast, but it’s a lot simpler, right? There (are) no kids crossing the street or anything like that. The other place will be in downtowns, urban centers, suburban urban centers, and with vehicles that only go in a limited area,” Estrada said.

“It’s absolutely going to happen, and it is happening now,” he said.

Autonomous cars are coming

The most advanced autonomous cars on public roads in Virginia today can completely drive on their own in certain circumstances, even though a driver does have to take over in more complicated situations, Viray said.

The Virginia Tech Transportation Institute is looking into how that changes what drivers do when sitting behind the wheel.

“I was afraid of using such systems, then after about 5 to 10 minutes I was pretty much reliant on the system already — and started to also do certain things that I probably shouldn’t have done,” Viray said.

More common, lower-level forms of the technology is already in mass-market vehicles, such as lane assistance, which alerts drivers who drift to one side or another, and automatic braking when a car detects another vehicle or obstacle ahead.

“If the system were to fail, or something went off, what’s the reaction time that’s given and how does the driver respond?” Viray said, adding that researchers are exploring.

Many automated vehicles today are relying on their own sensors, such as cameras or LIDAR, so Viray hopes the connected vehicle information can provide a critical additional piece to keep people safe.

“If an automated vehicle also has that information in addition to its localized sensors, then I think it’d save a lot of lives in different cases that it’s hard for an automated vehicle to do [without that information],” he said.

Connected vehicle information could have prevented a crash involving an automated Uber vehicle in March, Estrada said.

A woman turning left at an intersection could not see past other cars in the intersection to know that the Uber vehicle was approaching. The Uber vehicle went through the intersection as the light turned yellow, and the cars collided.

With an automated alert from a connected vehicle radio signal, Estrada said, the autonomous car or the woman driving the other car could have known to stop.

The radio signals to and from connected vehicles and road infrastructure can generally be detected from about 1,000 feet away.

Standards for the signals do include some security protections such as regular changes to vehicles’ identifying data tags and some attempts to guard against hacking.

Fairfax County hopes to draw companies working on autonomous and connected cars to the area.

“It is scary, but it actually could ultimately make the roads a lot safer for people,” Fairfax County Economic Initiatives Coordinator Eta Davis said. “It’s inevitable, it’s coming anyway, so we should be ready.”

In addition to potential safety improvements through reduced crashes, she hopes traffic could move more smoothly, and local governments could take advantage of the changes to provide better services.

Estrada, the eTrans CEO, pointed to even more dramatic potential impacts.

“This is going to change transportation more than anything since the Model T — everything’s going to change,” Estrada said. “Autonomous vehicles aren’t going to just change transportation and the auto industry; they’re going to change parking; they’re going to change how cities operate; they’re even going to change the organ donor program, because today most organ donors come from car accidents.”