This content was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

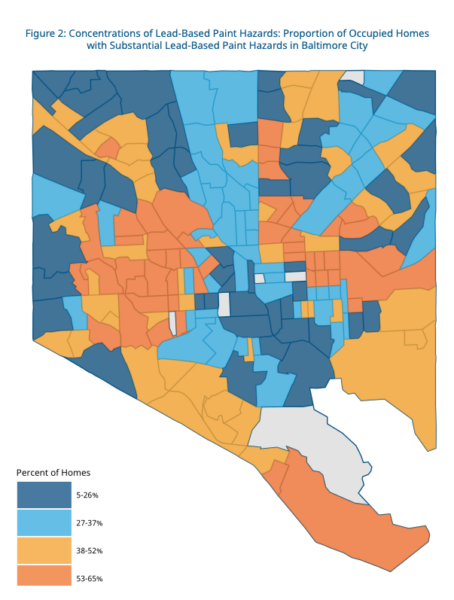

There are an estimated 85,087 occupied housing units in Baltimore with “dangerous lead hazards” — and the total price tag for lead abatement work on those units could be between $2.5 billion and $4.2 billion, according to a recent report from the Abell Foundation.

Lead hazard control for all of those units, which the report describes as “more limited in scope” compared with lead abatement, could cost between $851 million and $1.4 billion, according to the Abell report.

The Maryland Department of the Environment estimated that lead-based paint hazards accounted for 78% of all potential sources of lead exposure in Baltimore in 2021, according to the report.

Lead abatement includes removing, replacing or enclosing areas with lead paint and other hazards, whereas lead hazard control includes repairing and repainting areas with lead hazards.

Luke Scrivener, a Baltimore data scientist who authored the report, estimated that lead hazard control could cost between $10,00 and $17,000 for a typical two-story house, and lead abatement could cost between $30,000 and $50,000.

There are 2,104 housing units with reported lead violations in the city, according to the report, although 1,138 of those units are vacant or set to be demolished. Of the 966 occupied housing units, lead hazard reduction is estimated to cost between $9.7 million and $16.4 million, and lead abatement is set to cost between $29 million and $48.3 million.

Scrivener noted that Baltimore was the first city in the United States to ban lead paint in residential housing when it did so in 1951, and a federal ban was put in place in 1978, but the hazards still persist.

Scrivener used lead-hazard data from the 2011 American Healthy Homes Survey and neighborhood home values to estimate that about 42% of the 199,338 homes built in the city before 1978 likely contain significant lead hazards.

Scrivener noted that the American Healthy Homes Survey sampled housing units from jurisdictions that may not have had a lead paint ban before 1978, so applying those findings to Baltimore “may cause slight incongruence.”

“However, given that approximately 15% of Baltimore City’s housing stock was built between 1951 and 1978, this is likely to have a small impact on the results,” he wrote.

Baltimore largely relies on federal funding from the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development for lead reduction. The city received $9.7 million for that purpose in 2019, according to the report, up from $4.1 million in 2018 and $3.7 million in 2015, although the report notes that those grants “have many specific requirements about the types of housing units and households that are eligible to receive funding, which limits the pool of eligible homes and can create operational hurdles for the agencies administering the grants.”

“An attempt to totally eliminate lead hazards from all homes in Baltimore estimated to have lead hazards would require vast resources from federal, state, and local funders, as well as coordination across different levels of government and the private sector,” Scrivener wrote. “Even with increasing funding allocations from the federal government, the city is only scratching the surface of the widespread lead paint hazards, and city officials have to make difficult decisions about how to allocate those funds.

Every child in Baltimore is required to be tested for lead when they are 12 months and 24 months, according to the report. If test results show elevated levels of lead in the blood, the Baltimore City Health Department sets up home visits and inspections of the house where the child lives.

In 2020, 130 children under the age of 6 in the city were identified as having newly elevated blood lead levels, though testing and identification of new cases statewide went down as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Long-term exposure to elevated lead levels can cause myriad health concerns, and lead exposure generally tends to affect children more than adults, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Danielle E. Gaines contributed to this report.