A beach that was once a haven for Black music and celebrations will now be a place for anyone to come and learn about Black history along the Chesapeake Bay.

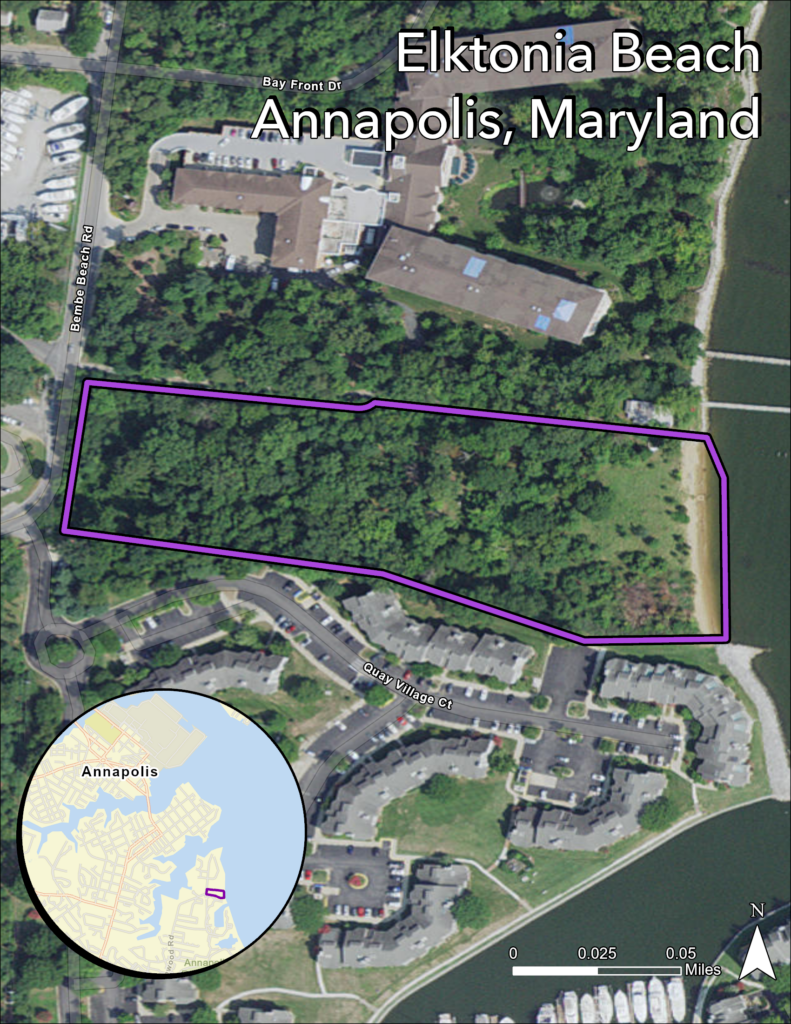

That five-acre piece of waterfront land on the Bay, Elktonia Beach, will turn into a park with access to the water.

“It’s a dream come true,” said Vince Leggett, the founder and president of Blacks of the Chesapeake.

The land, he said, was purchased for around $7 million.

The City of Annapolis, Blacks of the Chesapeake, Chesapeake Conservancy and the state of Maryland entered into an agreement with the Conservation Fund to acquire the property through a patchwork of funding, including federal, state and city Program Open Space funds.

On Thursday, with the support of U.S. Sen. Ben Cardin, the fiscal year 2022 spending bill also included $2 million in congressionally directed spending to the City of Annapolis, to support a state and local partnership effort to establish and develop a city park.

In 1902, Frederick Carr and his wife purchased 180 acres along the Bay, where he farmed and built a cabin. The couple had a grocery store in Annapolis.

From there, Carr’s and Sparrows beaches were privately owned and operated by Frederick Carr’s daughter Elizabeth Carr Smith and Florence Carr Sparrows.

From the 1930s through the 1970s, the “beaches” served as a spot for Black entertainment throughout the mid-Atlantic region during a time of segregation.

Leggett said in the late 1940s, William Adams, a Baltimore businessman, purchased five acres of land adjacent to the beaches that hosted James Brown, Little Richard, Billie Holiday and other big names in music.

“They had live music broadcast through WANN radio in Annapolis that showcased the stars who were coming and live broadcasts from the beach,” Leggett said. “People came from throughout the mid-Atlantic region to the venue.”

The beaches were in their prime, he said, in the ’50s and ’60s.

“This was during the period of segregation, when African Americans couldn’t go to parks and beaches and playgrounds and golf courses and swimming pools and things of this nature,” Leggett said.

It was a place for Black people to feel like they had a place they belonged during that time in history, he said.

“It was really a haven for African Americans to go someplace for leisure, recreation and entertainment, where they felt safe and didn’t have to look at the humiliating signs saying ‘whites only’ or ‘colored only’ and they could have some personal pride,” Leggett said.

The popularity of the beaches started to wind down after the Civil Rights Act, he said. The properties were then developed, and a water treatment plant was built on part of the land.

There is no timeline for the opening of the park just yet, as the planning stages are getting underway. Leggett, who has been working on the acquisition since 2008, hopes some of the area can start being used sooner rather than later.

The president and CEO of Chesapeake Conservancy, Joel Dunn, said he’s thrilled for the community that the plans for the city park are coming true.

“This parcel of land is symbolic of a significant part of Black history in the United States, as well as an important part of the City of Annapolis’ history,” Dunn said. “We are so grateful to the many partners and elected officials who helped create what will one day be a city waterfront park open for everyone to enjoy the Chesapeake while honoring our history.”